The first day of May 1968

Wednesday, May 1.

This is the first time we’ve seen a May Day parade since 1954, the year of Dien Bien Phu, when the tradition was interrupted. A few black flags, symbols of anarchy, flutter in the Parisian sky this May 1st, 1968. But they are just flags! The unions are peaceful.

In the late afternoon, Pompidou calls me on the inter-ministerial line: “You may know that I am leaving tomorrow morning for Iran and Afghanistan.”

(This ironic way of assuming I might not be aware does not please me; and his long absence worries me.)

AP: “Naturally. I plan to come and see you off at Orly.”

Pompidou: “No, no, it’s not worth it, we wouldn't be able to talk. Let's do it now.”

AP: “I am very pleased, because I am not without concerns.”

Pompidou: “You too? There are people around me who are worried about me leaving for ten days. I don’t see why I should cancel this trip. We’ve never been in such a good situation: no risk of a motion of censure, no social unrest, no worries from employers, no union preparations before autumn. It’s only your ‘enragés’ from Nanterre who are causing trouble. This is the time to respond firmly.”

AP: “Firmness, that’s all I ask for; it’s more in my temperament. But firmness by what means? With what enforcement? We are in a situation that no one can manage. Maintaining order and policing the faculties is the dean’s responsibility. It’s been proven at Nanterre itself, at the end of January, that if we call in the police, the students, ‘enragés’ or not, will gather to drive them off campus. Anyway, the professors’ council is against it, and Grappin won’t do anything against his colleagues. Who can stop the ‘enragés’ from invading the lecture halls? The dean, his assessor, and their small staff are completely incapable. Muscle-bound ushers? The Finance Ministry doesn’t want to hear about it, at least not before the new academic year.”

Pompidou: “Listen, I can’t get into the details... I’m just pointing out a new element that should help you shake off this general apathy. The communists, who are our adversaries everywhere, are becoming our allies this time! It’s a considerable change. We must take advantage of it.”

AP: “What I hope is that at the cost of suspending classes here and there for two or three days, like a month ago, we can make it to June. And then, everything is set to ‘clean up the kasbah’ of the university residence, not to keep the ‘enragés’ who have caused trouble or the students who have failed or didn’t show up for exams at Nanterre.”

Pompidou: “Try to act quickly. The communists’ turnaround is an opportunity not to be missed.”

AP: “Exactly, we are heading towards a showdown. Eight of the most excitable ‘enragés’ will receive tomorrow, or at the latest the day after tomorrow, a registered letter sent yesterday, indicting them and summoning them before the disciplinary committee at the Sorbonne on May 6, with a final judgment by the university council on May 10.”

Pompidou: “Have you taken your precautions? The academics aren’t going to back down, are they?”

AP: “Of course, I am personally receiving the main members of the disciplinary committee one by one, starting with the rapporteur, Flacelière. On May 10, these ‘enragés’ should be expelled from the university and consequently, as of May 11, Cohn-Bendit should be deported, according to the agreement made with Fouchet. What we can fear, of course, is that they will cause an uproar before they let themselves be condemned.”

Pompidou: “Well on that note, do not back down! I have very precise information —you know what I mean — about the communists' attitude toward them. They haven't forgiven Cohn-Bendit for preventing Juquin from speaking and driving him out of the amphitheater in Nanterre, nor for calling Laurent Schwartz a ‘bastard’ because he supports selection. The ‘enragés’ have made two major mistakes. The Communist Party is determined to crush them. Look closely at L'Humanité tomorrow morning. So, this is the time to be firm. When the communists are with us, we have nothing to fear.”

AP: “I’m not asking for anything else, but I remind you that I have repeatedly asked the Interior Ministry to expel Cohn-Bendit. You yourself agreed to release him, even though, in my opinion, there were ten reasons rather than one to place him in custody.”

Pompidou (annoyed): “You are not the Minister of the Interior or Justice. You are the Minister of National Education. Don't try to take your colleagues by surprise. Neither Fouchet, nor Grimaud, nor Joxe thought it possible to arrest Cohn-Bendit; they believed that his arrest would exacerbate the troubles instead of calming them. Therefore, the academics must take their responsibilities, which they hate. It is up to you to put them up against the wall.”

AP: “Flacelière promised me to make a ‘blistering’ requisition against Cohn-Bendit and his accomplices. But he cannot guarantee his colleagues' vote. I'm doing what I can, but I can do very little. I am convinced that we won't get rid of these troublemakers until we employ sovereign means, including the Court of State Security. Professors are not made for this work.”

Pompidou, visibly displeased, concluded: “Listen, it's your business; as the General says, sort it out.”

My answers irritate him. Like all of us, he is torn, depending on the latest information and interlocutors, between his deep liberal tendency, which is to trust the young people and especially the students, and his horror of disorder, which makes him wish for strong men and radical measures. He oscillates from one impulse to another. He precisely criticizes me for this, but hates that this criticism could be made of him.

Paris, Thursday, May 2, 1968.

This morning, I listened to an interesting interview with Raymond Aron by Yves Mourousi on France Inter 2.

Raymond Aron: “I tend to believe that French students would feel somewhat humiliated if they, too, did not have their own rebels. I say students because I am not sure we are witnessing the same movement of rebellion among working-class youth. (...) The two German leaders, Dutschke and Cohn-Bendit, seem to have this characteristic sometimes attributed to Germans of taking terribly seriously activities that are not that serious.”

On the ground, the day begins with clashes between far-left and far-right militants.

At 7:45 AM, a fire was started in the room used by the Groupe d'études de lettres at the Sorbonne, utilized by far-left students. The perpetrators left the signature of Occident militants on the walls: a Celtic cross. No one saw these arsonists, whose fire, quickly extinguished in this room, is going to ignite everything.

Curiously, Occident, which played such a decisive role at the beginning of the troubles, will disappear throughout May and until the fall. Prudence? Powerlessness? Collusion?

In protest, the Groupes d'études de lettres (FGEL) announced a meeting tomorrow, Friday, May 3, in the courtyard of the Sorbonne: “We will not let fascist students rule the Latin Quarter.” But they also defend Cohn-Bendit: “Students will never allow police repression to fall on one of their own through a university tribunal.”

Indeed, eight dissident students, led by Cohn-Bendit, have received the registered letter summoning them before the disciplinary commission on May 6. They and their comrades quickly understand that our cumbersome machinery offers them an opportunity to “Nanterrize” Paris. The enraged Nanterre students will not be judged in Nanterre, where they are beginning to be isolated, but in Paris, a territory where fresh forces can fuel the battle.

Nanterre, same day.

In Nanterre, the “March 22 Movement” launched a first day of “anti-imperialist struggle.” A significant “security service” prowled around the faculty, watching for the arrival of “fascists.” The “fascists” did not show up, but the Maoists from Rue d'Ulm came to offer their support: Cohn-Bendit sent them back to their school. René Rémond tried to conduct his class. A bench was thrown at him, he was booed, and he was expelled. A building in the residence was transformed into Fort-Chabrol. At 1:45 PM, a flyer from the “March 22 Movement” issued the slogan: “Out of Nanterre, the rat-catchers! Fascist commandos will be exterminated.”

Olmer and Roche went to Nanterre late in the morning. Grappin saw no other solution but to suspend classes, as they did in March. Exams are in fifteen days. The faculty can reasonably remain closed until then: “Moreover, after making our point, we plan to reopen it gradually if the situation allows.”

From the dean's office, Olmer phoned me the draft of the communiqué that the three of them had prepared:

“During the day of May 2nd, several classes could not take place due to deliberately created incidents and threats made against students, professors, and administrative staff. It is evident that the traditional freedoms of expression and work in use within the faculties are being openly flouted. Consequently, with the agreement of the Minister of National Education and the Rector of Paris, I have decided to take the following measures: from Friday, May 3rd, at 9 A.M. until further notice, classes and practical work are suspended at the Faculty of Letters in Nanterre. They will be progressively reinstated, subject by subject.”

I give my approval, adding: “All measures will be taken to ensure that, during the upcoming exams, consideration will be given to the temporary interruption of classes.”

In the afternoon, in my office, there is another working meeting about Nanterre. We finalize the arrangements that will allow the six hundred humanities students, spread out across six external locations, to take their exams despite the announced boycott. Potential disruptors will be charged with being caught red-handed, and expelled from the University. Absentees will be considered as having failed the exam. New “ushers,” for whom we have finally obtained funding, are in the process of being recruited.

We still believe that Nanterre will remain Nanterre. We cannot imagine that it will no longer be an issue. For the judicial schedule and the administrative closure set a meeting point for the Nanterre and Parisian unrest in the Latin Quarter.

Friday, May 3rd, 1968.

Pompidou's phone call from the day before yesterday becomes clearer: he already knew about Georges Marchais's polemic in today's issue of L'Humanité, “False revolutionaries to unmask.” It denounces “the factions” led by “the German anarchist Cohn-Bendit.”

“These pseudo-revolutionaries must be vigorously opposed... The intellectual leader of these leftists is the German philosopher Marcuse, who lives in the United States; according to him, university youth must organize for violent struggle... Their harmful activities, which attempt to sow disorder among the youth, should not be underestimated.”

At 3:30 PM, Narbonne, who is joining the Council of State after seven years with the General, comes to bid farewell. He is relieved: the decisions made at the Élysée last month regarding selection crown the efforts he had so persistently pursued with the General. I explain to him that, in my view, more than selection, it is competition between universities that can change things.

He is still in my office when Pelletier enters around 4:00 P.M., quite agitated: “Roche informs me that he has asked the police commissioner to evacuate the courtyard of the Sorbonne. Three or four hundred agitators, who seem to have come from Nanterre, have invaded it. A number of them are brandishing clubs and pickaxe handles.”

How can one criticize an act of firmness, the first spontaneously undertaken by the university authorities in months as the situation has deteriorated?

After Narbonne leaves, I nevertheless call back Rector Roche to ask for details. He is very calm: “Under all Republics, countless police operations have been conducted in the university buildings of Paris to put an end to disturbances.”

AP: “Do you have the agreement of your two deans?”

The rector: “Absolutely.”

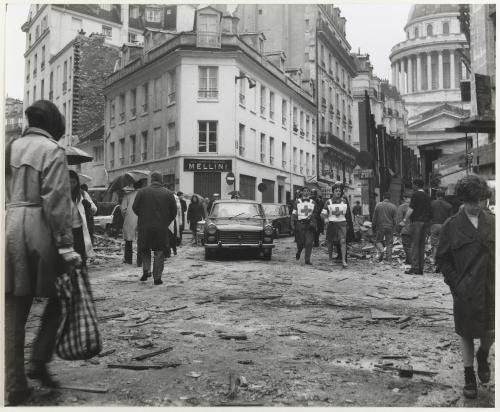

We soon learn that the buses in which the police are placing the evacuees, without violence or resistance, are suddenly attacked by young people who were outside. A long evening of violence follows — the first of this beautiful month of May.

There is a mystery about that first night. Neither the police nor the leftist leaders really understood this sudden violence. The only explanation they imagined and propagated was that a sudden solidarity had transformed the young people, the bystanders in the Latin Quarter, whether students or not, into “police breakers.” The aggressiveness of this spontaneous mobilization seemed all the more impressive. It convinced the public that the people of the Latin Quarter had risen as one against the intrusion of the police into the sacred precinct of the university.

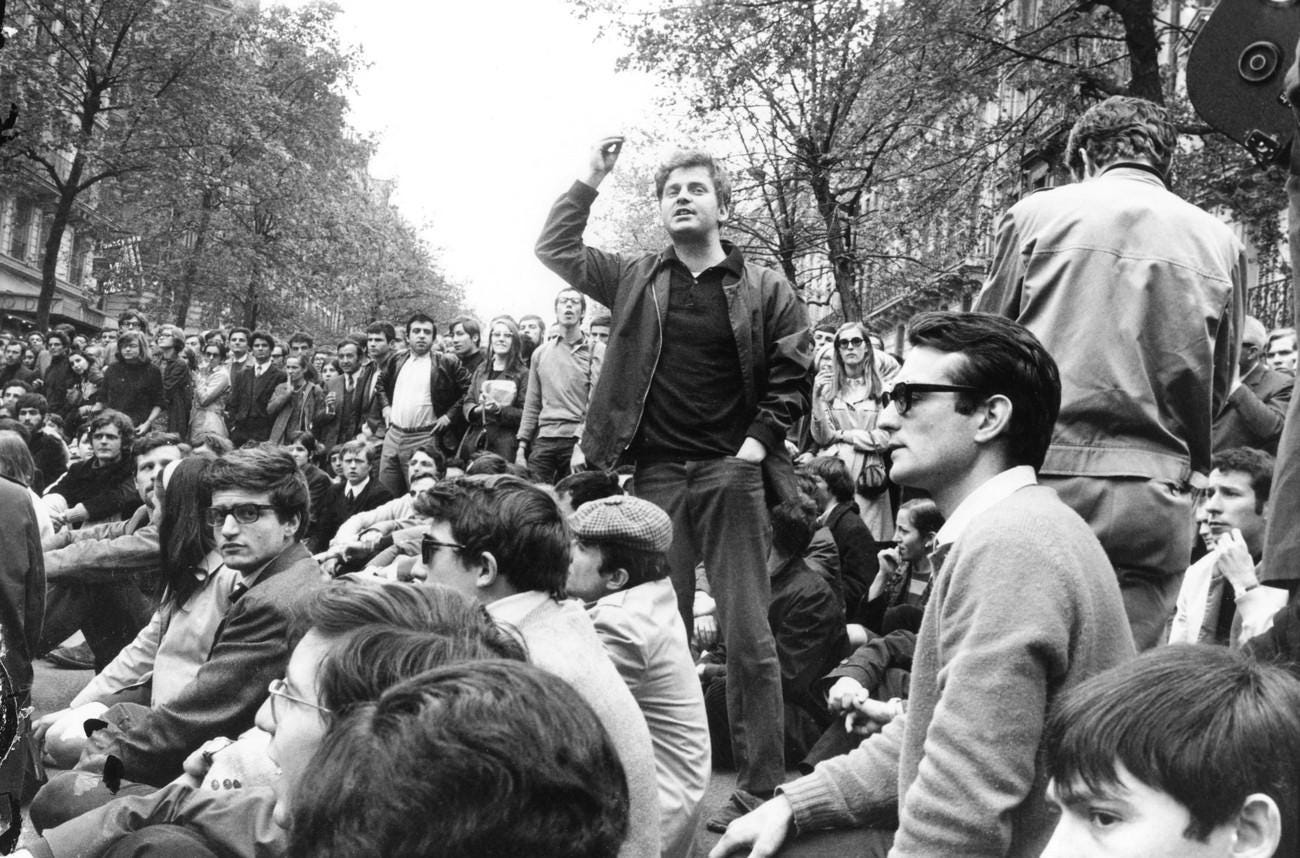

However, there was a simple explanation that I only learned thirty years later. The enraged who occupied the courtyard of the Sorbonne had a rescue army, and they didn't know it. It was the high school students from the CAL!, Romain Goupil, one of their leaders, recounts in his memoir film, Mourir à trente ans: “The students, our leaders, were there [at the ‘anti-imperialist day’] from 10 o'clock in the morning, with their wooden bars. We, the high school students, said no, we wouldn't be there until 4:30, after classes.” Sensible high school students still, who only demonstrate after school… But determined and organized militants, ready to clash with the militants of Occident — and who, upon arriving at the scene, saw their comrades being loaded into buses. Without warning, they fell upon the backs of the officers: “Being fifteen, throwing stones at the cops, and being protected by the crowd, absolute happiness! The cops were dumbfounded. So were the student leaders. They were in the buses and looked at us thinking: ‘It's not possible, it's working!’”

It indeed worked, but the CAL militants had been the rennet. Their decisive intervention completely escaped the police, and the “big ones” neglected to highlight this unexpected support from “those smaller than themselves.”

It wasn't understood that a revolution doesn't happen without revolutionaries, nor who the revolutionaries of that revolution were. This testimony shows with blinding clarity what the kindness or naivety of the Parisians did not want to see: that the fire had been started by real arsonists, sincere, convinced, pure and hard. Teenagers whose parents sensibly sold L'Humanité-Dimanche. They had absorbed anti-bourgeois ideology from infancy and rejected communism when it seemed sadly petty-bourgeois to them. From Leninism, they had learned the myth of the vanguard, the necessity of organization, the techniques of group action, violent provocation, urban guerrilla warfare. These warriors of '68, so few, so inspiring, live again in their truth through the images of Romain Goupil.

Escalation of events in the first week

Sunday, May 5, 1968

The General has decided to stay in Paris for the weekend, although he had planned to rest in Colombey.

La Chevalerie calls me in Provins after contacting Fouchet in Nancy. The General summons us, along with Joxe, the Minister of Justice and acting Prime Minister, to his office at 6 P.M. to discuss the situation following Friday's riot.

The General is very calm. He wants to show that in the absence of the Prime Minister, he feels it is his duty to personally handle matters that he would have left to the Prime Minister if he were present. We are in an ambiguous situation, where the role of the Prime Minister, theoretically held by the interim, is not fully enacted, and where the head of state partially assumes it.

Joxe informs the General of the verdicts just pronounced by the tenth criminal chamber: “The summary trial did not hold back: of the thirteen demonstrators brought before it, four, including two non-students, are sentenced to two months in prison without parole, eight receive suspended sentences, and only one is acquitted.”

Quite proud of himself, he emphasizes the exceptional severity of these sentences.

The General shows moderate satisfaction: “Well, it's better than nothing.”

Fouchet (inclined to calm, in front of an implacable General and a Minister of Justice pleased with having obtained significant sentences): “The important thing is that this punishment, unprecedented in years, does not provoke a reflex of solidarity or even revenge.”

CDG: “You think it was too much to sentence a few boys with suspended sentences, and four, including only two students, to two months in prison without parole, for a riot that lasted five hours and where these rascals stood out particularly? When there were hundreds of them throwing all sorts of projectiles at the police? You think that's excessive? The history of France is full of riots that only ended when a few dozen rioters were left behind.”

He questions us about the course of the fight; Fouchet and I respond alternately.

The General interrupts us: “If the police hadn't evacuated the Sorbonne on Friday, they would have had to evacuate it on Saturday or Sunday. It was finally necessary to react! It had been delayed too long! You can't blame the rector and the deans for rushing in, but rather for having dragged on for too long.”

The General gives Joxe and Fouchet firm instructions:

“No weakness! Once again, we must resist those who seek to attack the state and the nation. We cannot tolerate, now that France is at peace, the violence that we did not accept even during the most difficult times! It is truly regrettable that the selection process was not carried out in recent years! The university is full of all sorts of nuisances who have no business being there.”

The General is surely right in principle: it is necessary to demonstrate that one cannot rebel with impunity against public force by bombarding it with projectiles. But since January, we have seen so many examples of the passionate solidarity that emerges among youths whenever one of them is singled out, or whenever a uniform appears! I am frightened by the enormous chasm that has opened between the adult world and that of the youth, as well as by the solidarity that forms among the youth when the adult power shows its face. And while riots in French history may have ended with a massacre of rioters, who would even consider that today? Would the people accept it?

The General continues, as if he senses our hesitation through our silence: “What is exceptional is not these sentences, which are quite light, but especially that demonstrators in the streets are bombarding police officers with bolts and cobblestones and attacking them in hand-to-hand combat with pickaxe handles. We are far beyond mere contempt of agents or rebellion! This is an insurrectional riot! Anyone, students included, has the right to express their opinions verbally; but no one has the right to do so by combining words with actions. These are savage assaults that cannot be allowed to establish themselves in this country. It must be shown immediately, and with the greatest force!”

Fouchet (understanding that he must take a step toward the General): “The defense of the students did not hold. They all claimed that they only armed themselves to respond to an attack from Occident. That may have been true for those who were in the Sorbonne courtyard, but it was obviously not the case for those who attacked the police in the street. We discovered in their bags supplies of projectiles and bludgeons. They were not choirboys who started tearing up cobblestones and bombarding the police while protecting themselves with motorcycle helmets. They were commandos, they were an armed group.”

CDG: “Well, we need to draw the consequences! We are dealing with an armed organization whose goal is subversion.” (Turning to me.) “In any case, you are not reopening the Sorbonne! It must remain closed for at least a few more days.”

AP: “Except for the disciplinary committee, which will hear Cohn-Bendit and seven other ‘enragés’ tomorrow morning, and for the candidates for the aggregation in letters, whose exams start tomorrow. The rector decided yesterday to close the university, with my agreement, in order to protect these exams.”

CDG: “Of course, the exams already scheduled must be ensured. But classes should not resume until calm has been fully restored! Until then…” (turning to Fouchet), “You ensure that the Latin Quarter is tightly guarded! Make sure that these riots do not start up again! If they do, go all out!”

AP: “The university's disciplinary committee meets tomorrow morning at the Sorbonne to judge Cohn-Bendit and the seven other defendants. It would be surprising if they do not continue their agitation tomorrow, at least as much as they did the day before yesterday. Furthermore, they will be able to shout ‘Free our comrades!’ for real.”

CDG: “What exactly does this Cohn-Bendit have going for him? How does he manage to lead so many young people behind him?”

AP: “He has a great talent. He is alternately playful, nonchalant, and a destroyer of bourgeois structures, including the Communist Party. He is a revolutionary anarchist and an entertainer. He wants to destroy everything, and he does it so cheerfully that the media flatter and adore him. I am even told that peripheral radios might be giving him fat envelopes to ensure his cooperation. That deserves closer examination.”

CDG (addressing Joxe): “I wouldn't be surprised. You might want to discuss this with Gorse.”

Fouchet: “We shouldn’t panic. Let’s keep our composure. With students, we should never dramatize. Their anger rises like a pot of milk, but it quickly subsides if we don't give it more fuel.”

CDG: “When a child gets angry and goes too far, sometimes the best way to calm them down is to give them a smack.”

Joxe: “The problem is that they are no longer quite children, but not yet adults either.”

CDG: “We cannot take decisions based on the fleeting moods of these groups of teenagers who are being manipulated by leaders. We must make decisions based on our duties to the country. Mr. the Minister of the Interior, the police you command must maintain order with rigor. The law must remain supreme. Mr. the Minister of National Education, maintaining order is not your responsibility, but in order for the gullible not to be manipulated by the ‘enragés,’ you must address the issue of the University, explain what has been done for it, what will be done, the reforms you will implement, the orientation, and the selection.”

AP: “Regarding selection, I believe it is better to wait until the academic year is over. What I can announce is the orientation, the diversification of pathways, the construction of new institutions currently underway, and the expansion of IUTs.”

CDG: “When there is a riot, situations must be clear. Rioters must be made to explain why they are rioting. The authorities must know what they want, articulate it, and make it understood. If the authorities are not clear with themselves, how can those who obey them be clear?”

Turning to Fouchet and Joxe, he specifies: “We must immediately punish a few carefully chosen culprits. And if the violence continues, we will need to strike hard and arrest a few dozen or a few hundred protesters each time.”

Addressing Joxe, he adds: “This must be handled in flagrante delicto! Ensure that your magistrates do not delay things! The speed of the sanction is more important than the severity of the penalty.”

Turning to me, he insists: “As for you, you must explain the core issues, the ongoing reforms, and the selection we are going to organize. Open the file completely to the French public, just as you did the other day regarding orientation.”

Evening of Sunday, May 5, 1968.

The SNESup, meeting in the evening, decides on a strike of universities everywhere. Geismar, its General Secretary, in the final words of his speech at the Amiens conference, had announced that the university crisis might well be resolved “in the streets.” The warning turned into a directive. The crisis escalates, driven by this student movement extended into radical actions.

In response to the united front of SNESup, UNEF, and the leftists, I retaliate with the verbal statements of a communiqué.

The disciplinary board chaired by Flacelière proposes, as planned, expulsion penalties. The board is scheduled to meet on May 10.

I feel the need to loosen the grip of information that is exclusively academic, Parisian, and radio-based. What are people thinking in Provins? I have long felt that the mindset of my constituency accurately reflects the general sentiment. I improvise a public opinion poll in my own way, by calling ten friends whose judgment I trust. I ask each of them to call ten people every evening, question them about the situation, compile their opinions, and relay the summary to me. These one hundred indirect correspondents should themselves gather about ten reactions each: that amounts to a thousand daily respondents. By Saturday, I have set up my network. The method is not scientific, but I quickly understand that in Provins and thus in the provinces, people do not “show solidarity” with the protesters, do not find the leftists amusing, and are wondering when order will be restored.

After the evening news, Yves Mourousi questions me at length. I call for “an end to the escalation of violence.” I condemn the leftists and approve of the demand for a major university reform. I try to show that I understand the masses without excusing the minority. I explain the ongoing reforms and announce new construction projects. In short, I speak as a minister during almost ordinary times.

Locked away in the afternoon to prepare for this intervention, I don't realize that while I'm speaking, violence is once again erupting in the Latin Quarter. Throughout the day, a protest procession has been parading through Paris, under the watch of a deliberately discreet police force. But when the procession grows larger and moves closer to the Sorbonne in the evening, the police take action to oppose it. The clashes, very violent, continue until around midnight. The new factor is the omnipresence of the radios, which, live, move their listeners and inform the participants. Many French people, having both the TV and the transistor radio on, felt the incoherence. The General is one of those French people.

Salon doré, Tuesday, May 7, 1968.

I am summoned in the morning to meet with the General.

CDG: “Last night, your appearance on television was poorly timed. It was not good. It was clear, as usual, but you were on the defensive. You shouldn't have explained yourself at length on all the education issues.”

(Isn't that exactly what he had asked me to do: ‘open the file completely’?)

“You commented on your reforms as if you needed to apologize for them. It seemed like you weren't convinced of your own rightness.”

AP: “The academics and students are so sensitive in the current crisis that I thought it necessary to avoid an arrogant tone and to show openness to dialogue.”

CDG: “Dialogue! How do you expect to engage in dialogue with extremists who want to destroy everything? The only tone to take when there are riots in the streets is that of command! At a time when insurrection is breaking out, it's not the time to indulge in explanations. You should have quickly and succinctly condemned these agitators, called for reason, and rallied public support.”

AP: “We need to avoid having the mass of serious and hardworking students in solidarity with the extremists out of fear that repression will fall on them. The situation is delicate.”

CDG: “No! You need to speak firmly, express your outrage, the government's outrage, the people's outrage, the French people's outrage. And why did you allow yourself to be questioned by an extremist? He seemed to be accusing you. Was he another leftist?”

AP: “Mourousi is certainly not an extremist! But he is one of those young journalists trained in the American style, who frame their questions aggressively, in contrast to the obsequious interviewers of the past.”

CDG: “This is not the time for explanations; it's the time for indignation.”

I deeply feel the correctness of the General's criticism. If he had complimented me on my recent show about orientation, where I had calmly addressed the issue, it was because nothing significant was happening: we had all the time in the world. On a night of riots, that tone was not appropriate. It was necessary to be sharp. But curiously, he himself would make the same mistake on May 24.

Yet, I remain convinced that while it is indeed necessary to express strong indignation, it is still possible to engage in explanations.

In the afternoon, I hold numerous meetings. Can we halt the escalation? How? With whom?

Yesterday, one of my collaborators received, at their request and to their surprise, a group of Communist elected officials from the Paris region, including Juquin. After Georges Marchais's editorial, it was appropriate to gauge their stance. Their position is not clear. As the agitation intensifies, they do not want to appear as if they are coming to the aid of the “Gaullist regime.” They would appreciate it if we could rid them of the leftists, but they now only make such requests discreetly. Today, L'Humanité has nothing but praise for them. It is the government that is to blame for everything and is only seeking “an escalation of police repression.”

I meet with Noc, leading a delegation from the Federation of Paris Students, the Science Faculty’s student association — the small group of “moderates.” I inform them that I wish to resume classes at Nanterre and the Sorbonne as soon as calm is restored. To my surprise, they express their grievances about the brutality of the police, as if they too are affected by the solidarity reflex that makes the situation opaque and unmanageable.

I also meet with Marangé and Daubard. Today, I feel the strength of the relatively trusting relationships we have built over the past six months. I sense they are ready to assist me, that is, to help the Ministry of Education regain its composure. But they too adhere to the “three prerequisites.”

The issue becomes crystallized and clearer. Everything seems to hinge on the triple demand: release of the arrested students, no more police intervention in or around university premises, and reopening of the faculties. The most radical leftists have rallied to this demand, which appears so moderate, even non-radical. But the leftists know, with their very keen revolutionary instincts, that meeting these demands would discredit the judicial institution, delegitimize the police institution, and hand them the entire university space.

Street wise, Tuesday looks a lot like Monday. First, in the afternoon, Geismar holds a press conference: “We are willing to negotiate after our three prerequisites are met. To show our goodwill, tonight's demonstration will be as non-violent as possible.”

Indeed, it starts off like a grand parade, which Grimaud allows to wander through Paris. The march even crosses the Seine. A barricade stops it on the Alexander III bridge — behind it is the Élysée Palace. Undeterred, the procession immediately turns right, passes in front of the National Assembly without giving it a glance, crosses Pont de la Concorde, and, with Cohn-Bendit at its head, triumphantly ascends the Champs-Élysées singing “L’Internationale,” all the way to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which several of the “enragés” merrily urinate on, without anyone stopping them.

I stayed in my office with my key collaborators. We learn from the radios that the demonstrators are returning from the Étoile to the Latin Quarter, where, as yesterday, violent clashes resume at midnight. I call Dannaud to express my astonishment. “We are as surprised as you. Fouchet just unleashed the greatest anger I've ever heard from him against Grimaud. But Grimaud is probably right when he says that you can't control a crowd of excited young people the way you control a parade of veterans behind their flags. The number of demonstrators has significantly decreased, to 7,000, but their aggressiveness has increased.”

Around midnight, Geismar asks to speak on the phone with the cabinet officer on duty. I take the call myself.

Geismar: “We have just given the order to disperse and it is not being followed; it cannot be followed. There are 70,000 students in a state of great excitement, to whom it is impossible to give instructions.”

AP: “According to my information, they are more like 7,000.”

Geismar: “I doubt that. They can't be counted. What is certain is that barricades will rise on rue Monsieur-le-Prince. Clashes have already occurred. Blood will be shed if you do not ask the police to withdraw.”

AP: “How can you expect the government to leave the rioters in control of the streets? You have played the sorcerer's apprentice, and now you are overwhelmed.”

Geismar: “You alone can intervene. Announce that all the students' demands will be met, and then they will calm down.”

AP: “You who wish to overcome the immobility of certain elements of the university, should allow the state to fulfill its task, instead of preventing it.”

Geismar: “We tried to contact Matignon and the Ministry of Justice. There is no one anywhere. As for you, you refuse to do what I ask. So there is no state anymore!”

AP: “Do you think you're under the Fourth Republic? There is a state. It will do its duty. Do yours, which is surely not to fan the flames and then call for the firefighters.”

Geismar, as extreme as he is, is himself surpassed by even more extremists and is asking for my help to calm them... Strange, this arsonist surrounded by flames who cries for help.

On the role of the universities

Council of May 8, 1968.

Joxe is seated in the chair opposite the General. The session is primarily focused on student unrest.

AP: “The government cannot allow the calm necessary for education to give way to violence. It is certain that the vast majority of teachers and students share this concern, even if some have been led to acts of disorder or serious offenses detrimental to the very interests they claimed to defend in recent days.”

“The adaptation of the University to the demands of the modern world calls for profound transformations. These have been initiated and will be continued. It is a far-reaching undertaking that requires energy and perseverance. For now, the key is to ensure that classes can resume under normal conditions and to guarantee the freedom of exams and competitions. The government will work towards this. I will have the opportunity this afternoon at the Assembly to elaborate on its position.”

The General then spoke at length:

“From the current situation, we must take note of two things. The University is undergoing a fundamental transformation. As soon as high school students became baccalaureate holders, the university welcomed them. They went towards the disciplines they chose themselves. They were so few in number that there was no problem. When they obtained their degrees, they always found employment.”

“As we have democratized, a massive wave is arriving. The University will be overwhelmed. A complete change is necessary.”

“We are accustomed to keeping everyone. We let people choose the path they want, without worrying about whether we are piling people into lecture halls where they have no place. Many do not make it to the end. They stay there, they redo their year, they try to follow, or they don't even try, they lead to nothing. Studies extend indefinitely. Does one belong in university at 25 years old? No. And so there is agitation!”

“A profound overhaul of higher education is needed. We have provided it with enormous resources over the past ten years. But it does not have the means for planning. We must not hesitate to impose it. We cannot expect the teaching staff to plan themselves. That is not their mindset. They won't do it. Orientation, selection, and planning cannot be decided by the academics. It is a responsibility that the State must take. The Minister of National Education is there to make decisions after all necessary and useful consultations. We do not maintain the University for its own sake, but for the nation. It must provide the country with leaders, for the country as it is and as it is becoming, not for the country as it was. There must be control at the entry, orientation, and the elimination of the unfit.”

The General emphasized: “The University is not for itself, but for the country. An effort in this direction is underway. Recent incidents show that this is what it is about. Higher education must be adapted to the realities of the country.”

“And then, the second thing to note is the constant agitation, and thus the issue of public order.”

Without further elaboration, he turned to Fouchet, who explained his management of the disturbances. He notably said: “I believe there is manipulation. Last night, at the beginning of the demonstration in the Latin Quarter, there were students, but more high school students than students. It was still calm. It was like a traditional and good-natured parade. Then, gradually, things were taken over by much older people, in their thirties or forties, who were literally maneuvering their troops, some with whistles. From midnight onwards, there were far fewer high school students; the adults dominated. The police made several hundred arrests. Two-thirds were non-students.”

CDG: “If necessary, get reinforcements sent to you, gendarmes, CRS, mobile guards from the provinces, all possible reinforcements. We must call up the reservists. We cannot allow disorder to take over the streets! It's not possible! The violence must end!”

Fouchet: “There is an underlying phenomenon. The exploitation of a pretext, which is the entry of the police into the Sorbonne, has led to the mobilization of all those available for disorder. Maintaining order means arresting those who sow disorder. The UNEF is being led by the revolutionaries. When its leaders realized there was a risk of fatalities, they disappeared. Only the professional revolutionaries remained, who are remarkable organizers of disorder, who manage the troops they have at hand, know exactly what they want to do, and are solid and determined.”

“Out of the 160,000 students in Paris, less than 5% participated in these demonstrations, and it is always the same ones. The majority of the rioters are not students. They are people seeking revenge. We are witnessing the surfacing of troubling elements within society.”

CDG: “Since he must answer oral questions this afternoon in the Assembly, Mr. Peyrefitte will need to explain how the government envisions the organization of the University to ensure it meets the country's expectations. He must speak clearly and directly and answer the questions people are asking and that will be asked of him.”

The statement I prepared is approved by the General. It confirms that a major debate in the Assembly on the fundamental problems of National Education will take place next week, on the 14th, 15th, and 16th of May, in addition to this afternoon's debate.

The UNEF immediately denounces the “hardening of the government's position. It has not even touched on the three demands of the UNEF. On the contrary, it dared to speak again of selection and the need to plan education. It is a real provocation.”