De Gaulle meets with the Rector of Paris

Salon doré, Saturday, May 11, 1968, 6 P.M.

At precisely 6 P.M., the aide-de-camp ushers me in. The General has rosy cheeks, as he does during his great frustrations of recent years: the resignation of the MRP ministers, the condemnation of General Salan to simple detention, the disappointing results of the 1962 institutional referendum, the runoff of 1965.

CDG: “So, how do you view the situation?”

AP: “This revolt feeds on itself. It has no other goals than those born from its unfolding: obtaining the reopening of the Sorbonne, the release of the detained students, the withdrawal of the police forces. The few thousand demonstrators of this night have only these demands. They are supported by the residents of the Latin Quarter, whose sympathy they had already won, or who were outraged by what they call ‘police brutalities.’”

CDG: “What do you propose?”

AP: “To accept the three demands of the students, but simultaneously to require three guarantees in return: prohibition of any new protests; filtering at the entrance of the Sorbonne to allow only students; maintaining a few police vans until the reopening of the Sorbonne has taken place without incident and calm has returned.”

“Thus, we will make a gesture of both humanity and firmness. Less humanity, and we would turn the public against us. Less firmness, and we would strike a blow to the authority of the State and would no longer be able to plug the breach. The leaders of the National Education Federation had accepted this plan yesterday, but the agitators of the UNEF and the SNESup refused it.”

“There is nothing more to negotiate. These reasonable dispositions, it is enough to announce them publicly and sovereignly, and we will put public opinion on our side. It will feel reassured.”

“Especially since the opinion that is against us is that of the Latin Quarter, but that of deep France is for us. It will be even more so when it sees the images of the burned cars tonight.”

CDG: “Do you believe that deep France is for us?”

AP: “We must not be impressed by the poll conducted for France-Soir in Paris. I am sure that deep France does not share this sentiment.”

(I explain to him my daily polls in Seine-et-Marne.)

He looks interested but doubtful:

CDG: “Do you believe so?”

AP: “I am certain of it. This battle for public opinion, we should win it if we clearly announce our position.”

Rector Roche is ushered in at 6:15 P.M. He looks astonished upon seeing me. Had he not been informed that he would be received in my presence? It will be difficult for him to carry out the mission entrusted to him by the deans. This second quarter of an hour is surreal.

The General stands up, greets him courteously, and has him sit down: “You are the Rector of Paris?”

Roche, taken aback, responds after a brief silence and in a hesitant voice: “Yes.”

CDG: “And you will remain so!”

Has the General heard of the exhortations to resign that Cohn-Bendit, Touraine, and his other nighttime visitors, as well as the assembly of the Faculty of Letters this morning and some members of the University Council, have given to the rector? It is clear that the General does not wish to have the rector's resignation on his hands and that he wants to strengthen him in his position.

Roche, regaining his composure, says to the General: “Some have demanded my resignation. I thought it would be an abandonment of my post. I refused.”

“Very good,” says the General, nodding strongly.

The rector: “It is a bout of madness. We must not give in. But neither must this madness spread. The calmest people are losing their composure, the most reasonable no longer know what they are saying. The problem is that the madness was, until last week, confined to the heads of a few extremists; now it is spreading to thousands of students, hundreds of assistants, teaching assistants, and even professors.”

The General then asks the rector questions about Nanterre, the Sorbonne, the past few months, and the past week. During this interrogation, I remain silent, as the rector says nothing that I do not fully approve of.

CDG: “Were there any precursory disturbances at the Sorbonne? Did you suspect that the courtyard of the Sorbonne would be invaded?”

The rector: “Of course not! The invasion of the courtyard came like a bolt of lightning. There had been some incidents, some skirmishes between extreme right-wing and extreme left-wing students, a fire started by the extreme right. But nothing could have led us to suppose such a mobilization at the Sorbonne. There were only problems at Nanterre, which we explained by a deplorable environment, poor communications forcing people to stay on campus all day, and difficult working conditions. Apart from Nanterre, there were no problems.”

After a quarter of an hour, without revealing what he intends to do, the General stands up: “Well, Mr. Rector, thank you for enlightening me.”

While signaling me to stay, he amiably escorts his visitor out at 6:30 P.M.

CDG: “He is very good, your rector…" He sits back down: "So, what do we do?”

AP: “For the students of good faith, the velvet glove. For the revolutionaries, the iron fist. We erase everything and we do not start again.”

I read out the balanced plan that I have written down: The three demands of the leaders can be satisfied if accompanied by measures to prevent the troubles from recurring:

“1) Release of the detainees and amnesty. It is sufficient to declare that the prosecutor's office will not oppose the request for release that would be presented by the four detained students. We can announce that we will submit a bill for amnesty for the disorders that occurred between May 3rd and May 11th. But gatherings and demonstrations will be prohibited until further notice, with the exception of the one announced for Monday, for which the major trade unions will ensure order. If new troubles occur, the amnesty law will not apply to the troublemakers; their student cards, if any, will be withdrawn; foreigners caught red-handed will be expelled from France.”

“2) Reopening of the Sorbonne. Yes, but for the normal resumption of classes and exams, not for ‘occupying it day and night’ by holding meetings there. A filtering system will be organized to allow only students who normally have access, as well as teachers and staff, to enter.”

“3) Withdrawal of the police from the Latin Quarter. Yes, gradually. A van must be stationed on Rue de la Sorbonne near the entrance to block any potential commando that might try to force its way in. The police would obviously have to return to the Latin Quarter if the disorders resumed”

“Thus, we satisfy the three student demands; we prove our goodwill; we remove any pretext for them to start again. But we accompany these three concessions with serious guarantees. Last night, the leaders refused this compromise that was offered to them. They will find it difficult to refuse if we announce it publicly. Otherwise, they would prove their bad faith and demonstrate that their real goal is to do a revolution or at least cause chaos.”

“Finally, a body of ‘wise men,’ including moral and spiritual authorities as well as professors and students, could immediately determine the conditions for a return to calm and work in the faculties, and in the long term, outline the main lines of a reform of the university system.”

“But at the same time, although it is not my responsibility, it seems necessary to prepare immediate measures in case attempts at subversion intensify: state of emergency, prosecutions before the Court of State Security for threatening the internal security of the State, or even Article 16 (in any case, the threat of resorting to it).”

The General listens to me without interrupting. He has me clarify each of the three points and their counterparts again. The triptych of limited concessions balanced by their compensations visibly suits him.

I then announce the modest card I have in reserve: “General, I have indicated to you what seems advisable to do. I would fully understand if you felt differently, but then I would fear not being the right man for the situation. If this plan reveals that my vision of things is too far from yours, or if you simply believe that someone else could better contribute to resolving the crisis, my portfolio is naturally at your disposal.”

He gives a slight start, as if I had uttered an incongruity. The General's right arm sweeps a quarter circle, swift as a broom stroke: “No. You stay. When all this is over, we will take stock and see if another sector would be more suitable for you. But until then, you hold firm!”

Having quickly dismissed this hypothesis, he continues: “Your plan has the advantage of giving us the noble gesture, but at the same time of regaining control.”

He reflects for a moment, his gaze lost in the foliage of the park. He then delves into the details: resumption of classes, modalities of filtering, presence of a police van on Rue de la Sorbonne to deter troublemakers…

He concludes: “This is what we are going to do. Until the general strike on Monday, nothing will happen. We will meet here tomorrow morning. We will finalize this plan and the Prime Minister will announce it afterwards.”

He looks relieved, as if he clearly sees a way to escape both the unconditional surrender that would humiliate the State and the stubborn refusal that would block the situation. He accompanies me out at 7:15 P.M.

Prime Minister Pompidou returns to Paris from the Middle East

Saturday, May 11, 1968, 7:15 P.M.

When I take leave of the General, Flohic, with a transistor radio pressed to his ear, tells me: “The Prime Minister has just arrived at Orly. He told the journalists that he has very precise ideas. I suppose he will share them with you and inform the General.”

I rush to Rue de Grenelle. I call Tricot to update him on the General's conclusions. “I have just left his office,” he tells me. “He explained all of this to me and told me to arrange a meeting in his office for tomorrow morning, with the Prime Minister, the Minister§ of Justice, the Minister of the Armed Forces, the Minister of the Interior, the Minister of Information, and yourself. He even dictated the main lines of the balanced plan that could be adopted and that the Prime Minister would announce afterwards. He has perfectly memorized what you told him.”

Matignon, Saturday, May 11, 1968, 8 P.M.

The Prime Minister has summoned Joxe, Fouchet, Messmer, Frey, Guichard, Gorse, and me.

Almost every night for the past eight days, Joxe, Fouchet, and I — although the maintenance of order is hardly my concern — have barely gone to bed before 3 or 4 A.M. And last night, we did not sleep at all. We look at each other: we have drawn features and pale complexions, next to a fresh and rested Pompidou despite his journey. One understands why Joffre attributed the victory of the Marne to having slept well. Pompidou brings us his serenity. He is impressively self-assured: “I have been kept informed as things progressed. The wait was long... All this is a crisis of hysteria. I have the advantage of being untainted. I am the only one able to reset the counters to zero and to reconcile us with the students.”

Pompidou, like Grimaud, says “the” students. Although there were many high school students and even more individuals with no connection to the University on the streets during this night of barricades, and less than 5% of the students from the Paris metropolitan area.

He has prepared, during the return flight, the text of a speech which he reads to us, with the key phrase: “‘I have decided that the Sorbonne will be freely opened starting Monday. Classes will resume at the discretion of the rector and the deans.’ Do you have any objections?”

Everyone remains silent. Joxe and Fouchet pleaded this cause unsuccessfully with the General this afternoon. Are they waiting to see if the Prime Minister will do better?

I decide to break the silence: “Firstly, your proposals will be insufficient in the eyes of the demonstrators. The reopening of the Sorbonne has become a secondary issue. Their main demand is the release of the four detainees.”

Pompidou acknowledges this objection and adds a sentence to his text, which we formulate together: “The court of appeal will be able, in accordance with the law, to rule on the requests for release submitted by the convicted students.”

AP: “That’s for the concessions. But if there are no counterparts, your clemency will have the effect of a capitulation. Measures should be taken to ensure that the Sorbonne is not open to everyone. We are not dealing with good little students who only ask to resume their classes and take their exams. You are dealing with revolutionaries who want to occupy the Sorbonne day and night to make a revolution there. If you freely open the Sorbonne, you will not be able to evict them. You risk triggering an avalanche.”

Pompidou: “What do you want them to do there, day and night? They will quickly tire themselves out and tire everyone else if they want to hold continuous meetings. When they have talked a lot, they will eventually fall silent. No! We either trust or we don't. If we put conditions on this act of clemency, we will eliminate all the psychological effect. We must not skimp.”

I take the floor again to express my fear that contagion will spread throughout the country.

Pompidou: “What contagion? The unions have never been so quiet. The communists are hostile to the leftists. Don't worry. I know what I'm doing.”

In short, Pompidou thinks that the “iron fist” part of my plan would spoil the “velvet glove” part, which is the only one that should be retained. No stick, nor threat of a stick: we must resolve to give only the carrot, and the whole carrot.

Pompidou concludes: “If the leftists want to make a mess, it will turn public opinion against them. Our best card is the demonstration of the unreasonable consequences of their actions. We are going to open the doors freely. Let them fend for themselves.”

I make one last attempt.

AP: “Why rush? Nothing will happen before Monday afternoon. I fear that afterwards, we will not avoid contagion throughout the country. It would be better to take the time to weigh the consequences. Why not wait until we meet tomorrow to make these decisions?”

(I did not feel authorized to announce what the General had just decided: a meeting in his office tomorrow morning.)

Pompidou: “No, no! We must not lose a single hour. I was even tempted to indicate my intentions upon arriving at Orly. But I had to discuss it with the General first.”

He continues sharply, without any of my colleagues having opened their mouths: “Listen, my decision is made. I only need to have it approved by the General and to announce it.”

It is useless to insist. Pompidou is inflexible. But I have no doubt that he will soon clash with the General, who refused us this week what we proposed to him in this sense, even though we surrounded it with strong precautions that the Prime Minister does not want.

We leave. Joxe and Fouchet seem relieved to see the Prime Minister spontaneously taking on the solution they advocated. Joxe whispers in my ear: “Will he win over the General? This is going to be interesting.”

I return home and make a few phone calls in Seine-et-Marne. The tone of my “panel” remains the same: “Above all, do not soften!”

Saturday, May 11, 1968, 11 P.M.

Pompidou speaks on television. I am stunned. He has had his approach approved. The General, two hours earlier, had given me his complete agreement, had confirmed this decision to Tricot, and was preparing to implement it tomorrow morning. And he rallied without a fight to a diametrically opposed attitude?

Either he is under influence, he who had never been said to be influenced by anyone: the influence of a man whose competence, energy, and self-control impress him, and even intimidate him when it comes to the University and youth, areas where he feels less sure of himself. Or, he is no longer de Gaulle, but a man who feels his strength diminishing and who is too happy to leave the responsibility to his second-in-command, who boldly asks to assume it. I see no other hypothesis.

It is true that he will give me a third one later.

I am dismayed. If the reopening of the Sorbonne and the release of the convicted students were to be announced, it would obviously have been better to do so before the riots of last night. How could the French not feel this U-turn as a disavowal by Pompidou of his own government and therefore of the General himself.

Peyrefitte offers his resignation

Rue de Grenelle, Sunday, May 12, 1968.

I had summoned the rectors and deans of the University of Paris to my office at 9 A.M. to prepare for the meeting at the Élysée, which was supposed to finalize my balanced plan, which Pompidou has thrown in the trash. By necessity, our morning meeting changes its purpose.

From the outset, I clarify that I have offered my resignation to the President of the Republic, who has refused it. I recall the events of the past nine days: “And now, how do you see the future?”

Zamansky, the dean of sciences, the most optimistic, thinks he can regain control of his professors and lecturers, who in turn would regain control of the teaching assistants and assistants, and they would calm the students…

The dean of law, Barrère, is confident: it is enough for each faculty to have a few “strong attendants,” like those he has, whose mere presence is enough to keep the agitated, who are not numerous in his faculty, in check.

Poitou, the dean of sciences at Orsay — my classmate and a very active unionist — tells me bluntly that, in his faculty, classes will resume when “the” union decides, but not before.

On the other hand, Roche, Grappin, and Durry have no illusions: university activities will not resume before the summer. Since the immediate and unconditional reopening has been decided, there is nothing to do but wait and see what happens, which can only be the onslaught of the enraged. But they do not blame the Prime Minister for his choice: his clemency should pay off in the long run.

We talk at length about the problems of the return to school and the organization of the university.

Beyond the opinions expressed by each person, I have the strange impression that, like me, these great academics sense, without yet saying it, that the University of France will never be the same again. A new university will be born. We know only one thing: it will be in pain.

I write to him by hand, on my personal stationery:

“9, rue Le Tasse Monsieur le Premier ministre, Paris, Sunday, May 12.

Yesterday evening, you made a wager. I had previously pointed out the perils to you. I hope you win it! But by remaining in the position I hold, I would only diminish your chances.

I have respected — while trying, unsuccessfully, to calm the spirits — the instructions of firmness that the General had given us.

Now that you have made him accept a policy opposite to the one I had been instructed to implement and that, willingly or not, I symbolize, it seems desirable that a new man take my place.

Please believe, Monsieur le Premier ministre, in my faithful devotion.”

I have this letter delivered in the afternoon to his private residence, Quai de Béthune, by my driver and my inspector. The latter learns that the Prime Minister is spending Sunday in Orvilliers; he leaves the letter with the concierge, with the promise to give it to him upon his return.

Monday, May 13, 1968.

I call Joxe: “It's still a shame that we missed this negotiation! There is something absurd in this gap between a night when we fought to refuse concessions — and the next evening when the Prime Minister, upon returning, grants all these concessions without a fight!”

Joxe: “I told you, Pompidou forbade me from making concessions. He wanted to be the man who granted what the wicked had refused. I don't know what will happen in the coming days. But I am sure of one thing: Pompidou will one day be President of the Republic.”

I call Jobert: “Did the Prime Minister speak to you about my letter from yesterday?”

He doesn't seem to understand.

AP: “Did he tell you that I offered him my resignation?”

Jobert: “Your resignation? Of course not, it’s out of the question! He thinks you will help him straighten out the situation.”

I cannot leave it at that.

Matignon, Monday, May 13.

I confirm to him, in a more official style, my note from the previous day, and have it delivered by my collaborator Dorin as he is sitting down to eat; he summons me for 3 P.M. and dismisses my proposal.

Pompidou: “It’s out of the question. If you leave, people will say that I hold you responsible for the situation. We are not the republic of scapegoats. All this will have calmed down within forty-eight hours. Now, try to reconcile with the academics, who blame you for the police entering the Sorbonne.”

I recount to him the story of a “de-escalation” sabotaged by the leftist leaders. I realize that he is not aware of it. He is surprised: “It wasn't the General who imposed this decision on you?”

I correct him.

AP: “I have learned to believe what these young revolutionaries say. You will see, starting tonight, they will occupy the Sorbonne in their own way, the way we have already seen at work in Nanterre.”

Pompidou: “In any case, we could not have prevented the Sorbonne from being stormed.”

AP: “How could anyone have told you that? The demonstration at Denfert-Rochereau is certainly impressive, but it is well controlled by the CGT's security service. The leftists would have been unable to lead the masses; and if they had tried to break away, there might have been a tough fight, like the four we endured on the 3rd, 6th, 7th, and 10th, but they would not have won.”

Pompidou: “There are 200,000 of them. Nothing can be done against 200,000 unleashed demonstrators.”

I break off. I prefer to propose to him some ideas to put the university to work on bases other than the “critical university.”

AP: “I am thinking of a committee of wise men, something like the Massé commission during the miners' strike. We could also introduce student representatives within the Capelle commission; and create a national structure to study the student condition.”

Pompidou (as if distracted): “Yes, perhaps, we will see later.”

Then, I enumerate for him, for the student groups, security measures to be taken in case of a resumption of violence: state of emergency, prosecution before the Court of State Security for threatening the internal security of the State, Article 16.

He exclaims: “You are obsessed with dark ideas! Thinking about the state of emergency, the Court of State Security, Article 16, because of these kids, that's insane! It's as if you've never been twenty! Pull yourself together! All this will be over in forty-eight hours!”

AP (changing the subject): “We had planned for this week three days of debate on National Education. Are you still in agreement with the principle? Since tomorrow is reserved for your statement, should we reduce the three planned days to two days, or postpone to next week?”

Pompidou (he hesitates for a moment): “Do you think this is the right time?”

AP: “Yes, more than ever. You have regained the initiative with a spectacular gesture. But the essential initiative of the government is to define the rules that allow us to get out of disorder.”

Pompidou: “Are you ready on the substance?”

AP: “More than ready on the three major reforms that we have been preparing since the fall and that have not yet been debated in the Assembly. On orientation in secondary education. On pedagogical renewal, at all levels of education. On selection and the autonomy of universities. Simply, on this last point, you deemed that a law was not needed but a decree, and with what is happening, I can only agree with your decision.”

(I sense he is receptive, so I insist.)

“We must occupy the deputies with something other than running the streets. My statement will have to be precise to the millimeter; I will of course submit it to your approval. It could serve as the basis for hearings by the Commission on Cultural Affairs, which could hear all the responsible parties, academics and students, unions and employers. This would keep the debate at the Palais-Bourbon, where it legitimately belongs, and not in the streets or in lecture halls dominated by the enraged.”

“We must offer the students the opportunity to participate. The teachers did not want it, but now that they want to catch up, they can no longer oppose it. The Napoleonic University must burst into autonomous universities — under the guidance, of course, of the State, which is the only one capable of successfully managing the transition.”

Pompidou does not give me a definitive yes or no: “We need to see how tomorrow's session goes after my statement, and how the motion of censure is presented.”

Pompidou claims “the General has changed”

It is time to conclude.

AP: “You have been too successful at Matignon, if you allow me to say so. Your presence at the summit of power is very strong, your ability to influence the General is incomparable. Your absence has caused an imbalance in the functioning of the State. If you had been here, things would have turned out differently.”

Pompidou, very relaxed, smiles: “I see what you mean.”

(I'm not so sure.)

“It's true that, when you have to be replaced, you don't tend to look for someone who will warm your seat.”

He is obviously thinking of Debré, whom he had no desire to be replaced by; whereas with Joxe, he had no fear of being supplanted. But I was not only thinking of that. If Pompidou had lived through the previous week day by day, he would not have made the about-face of the night before last.

Pompidou lowers his voice: “You know, none of this would have happened if… The General has changed...”

Twice — after the “dominant and self-assured people,” after “free Quebec” — Pompidou has let slip a similar word to me; twice, he has lowered his voice, even though no one could hear: it's his way of making it understood that it's a secret remark.

“You see, the General is no longer the same. He has aged. He no longer has the same sensitivity to the consequences of the initiatives he takes, to the impact of the statements he makes.”

If he has repeated this terrible judgment to me in this way, without remembering that he has already said it to me, it is because he must have said as much to others. It is clear that, for Pompidou, the moment is approaching to take the General's place, in the interest of the country. But these are expressions he only uses in private. His entire attitude shows that he is obsessed with this idea and that he considers it his duty, like a loving son, to cast the cloak of Noah over the General's weakness.

It is a superior loyalty. Yet, in this case, is he right in his intuitions? I believe it is the General who is right.

Weakness, failure of the General? If there is a failure in lucidity, it seems to me to be complete in the Parisian political class, including the ministerial cabinets; and only the General and the old guard of the RPF, to whom he has instilled the cult of the authority of the State, the last resort in trials, escape it in my eyes.

Jobert enters Pompidou's office: from Place de la République to Place Denfert-Rochereau, there are several hundred thousand demonstrators. Red and black flags are being waved. Banners proclaim: “Ten years is enough!”, or: “May 13, 58, May 13, 68, happy anniversary!”, or: “Power retreats, let's make it fall!”.

Sacrilegious cries are launched: “De Gaulle to the archives”, “De Gaulle to the hospice”.

Pompidou, laughing and incredulous, says to us: “They're not going to throw us out for this tenth anniversary!”

As he accompanies me to the door of his office, he repeats in an insistent tone: “Are your collaborators aware of your letters?”

AP: “Absolutely not.”

Pompidou: “You do not speak to anyone about this resignation, do you understand? No one, not even your wife!”

Subtle as amber, he has sensed that the announcement, or even the rumor, of this resignation could cast a shadow over the authority he needs to win his bet.

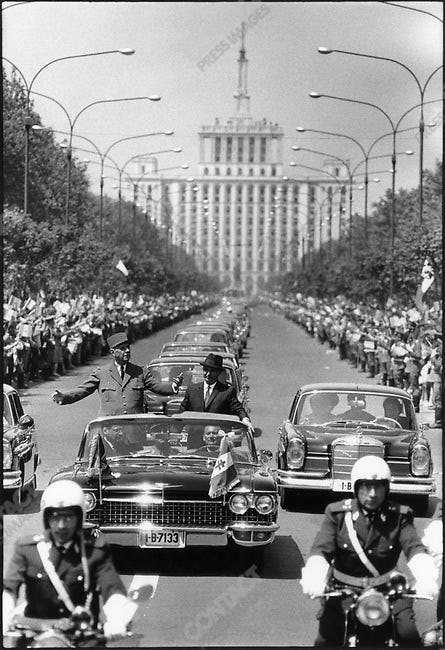

General de Gaulle heads to Bucharest

Orly, Tuesday morning, May 14, 1968, 7:15 A.M.

A small half of the ministers are at the “isba” in Orly: we have come to bid farewell to the General, who is flying to Bucharest. From Fouchet's mouth, we learn that we almost came for nothing. Between midnight and 1 A.M., he urged the General to cancel his departure.

The General argued that Romanian opinion would not understand if he canceled. Fouchet replied that French opinion counted more than Romanian opinion in such a dramatic moment.

Then, Pompidou and Couve arrived at the Élysée: “You cannot cancel this state visit at the last moment,” said Couve. And Pompidou: “The difficulties are behind us. If you cancel your trip, you will give the impression that it is not over, that things are more serious than they are.”

Pompidou arrives at the isba, soon followed by the General, who shakes our hands and gathers us in a circle around him: “I was tempted last night to cancel my departure. But this trip is very important for our international policy, for détente. If I had canceled it, the effect on the world could have been disastrous. Bucharest is less than three hours away by Caravelle. We must not give the student agitation more importance than it deserves.”

He specifies to Gorse: “I will speak on May 24th: you can announce it. I will tell the country what I think of this agitation.”

Why set a television appointment so far in advance? He had already done so for the barricades in Algeria and for the putsch. But he made people wait two or three days, not ten.

What will happen in these ten days? Either, as Pompidou announces, everything will have calmed down, and the intervention will be unnecessary; or the agitation will continue, and no one can yet say if it will be the right time to intervene. Obviously, he wants people to be in suspense: “What will he have to say?” It is still strange.

When the plane has taken off, Fouchet pulls me by the arm and offers to ride in his car, while mine follows.

Leaning towards my ear so as not to be heard by his inspector, he whispers: “Pompidou clearly wants to be the only one at the helm. The General gives the impression of being tossed about, leaning towards one decision, then towards the opposite, from one quarter of an hour to the next. I have never seen him so hesitant. He ended up following Pompidou's advice, against my will.”

After a silence, he adds: “You know, I wonder if you weren't right when Pompidou returned. The unions are saying that the government has gotten down on its knees, that this is the time to make demands. There is no reason to hold back. Pompidou surrendered with panache, but he still lost his pants. He would have done better to give himself twenty-four hours to reflect.”

How I understand the General's hesitations! Seen from Sirius, it would have been a shame for him to cancel a trip where he could sow seeds of independence and chip away a bit at the Soviet bloc. Besides, if he had stayed, what could he have done, given that he had given Pompidou carte blanche? But, seen by French public opinion, this visit where the General will be wildly acclaimed by the Romanian crowds, and particularly by the students of the University of Bucharest, will seem surreal.

Matignon, Tuesday, May 14, 1968.

I am not regularly summoned to the morning meetings with Pompidou on maintaining order: I do not complain, it is not my affair. Today, however, I was invited.

Pompidou, as always perfectly in control of his nerves, speaks with a humor tinged with gravity about the terrible moments when troops fired on demonstrators: 1830, 1848, 1871, February 6... He concludes this brief digression: “That is what will never happen in Paris as long as I am here.”

Fouchet, Grimaud, Jobert look at him. One can sense a deep agreement passing between them: if this period does not include a bloody page, it will be largely due to this shared resolve.

Debates in the Assembly

Palais-Bourbon, same day.

At 3 P.M., I go before the Gaullist group of the Assembly. Contrary to my expectations, I am received warmly. The doves recognize that I had gone as far as possible in the direction of extending a hand. The hawks, astonished to see that Pompidou has gone much further than I, realize that things are less simple than they thought.

Then I join Pompidou, who has asked to see me before the debate, in the office reserved for the Prime Minister.

Pompidou: “I know what I am going to say to begin with. But the debate will go in all directions. I will need to conclude with concrete and immediate perspectives. For Education, how do you see them?”

AP: “I am convinced that we can bounce back from the crisis by going further and faster than we thought. Why not make a solemn declaration, proclaiming the necessity of a new University! Show that the ministry is ready to discuss with everyone the measures to be taken.”

“I see three basic principles: 1) the autonomy of each university; therefore their progressive differentiation; 2) the participation of students in university management, even co-management; 3) the reconsideration of pedagogy, the content of studies, the methods of evaluating the value of students.”

Pompidou (he raises his arms to the sky): “What you are proposing is a revolution! You can see that this is not the time.”

AP: “What is underway is indeed a revolution. If it is not done with us, it will be done against us.”

Pompidou: “The problem is that anything that comes from the ministry or is announced by you will be rejected. It will be declared that you only came to it under pressure from the street.”

AP: “It is easy to recall that I have multiplied the warnings and cautions before the student agitation! I have shown that immobilism would lead us to an explosion. Besides, many mandarins reproach me for it!”

Pompidou: “Perhaps, but no matter what you do, you will inevitably appear to be trailing behind the revolutionary students.”

AP: “But the Committee of Wise Men, which I mentioned to you, would serve to depersonalize the approach. It would gather ideas that will inevitably come from everywhere. Moreover, there should be as many reflection committees as there are academies, and the university authorities should participate in the ongoing discussions or even, if possible, organize them. It is essential to avoid the impression that the reforms will be concocted and imposed from Paris.”

Pompidou (he shakes his head): “The fury of the revolutionaries must discredit itself through its excesses. That is how we will get out of this.”

A few minutes later, he goes up to the podium for a remarkable statement, which will be followed by the interventions of the opposition speakers, notably Mitterrand.

In recounting the history of this decade, Pompidou did not say a word about the General, nor about Joxe, nor about Fouchet, nor about me. But it is as if he subtly disavowed what had been done in his absence. The impression prevails that he wants to take university matters into his own hands.

Mitterrand attacks ferociously: “What have you done with the State?… What have you done with justice?…”

To Mendès France, to Sudreau, who have launched their barrages, Pompidou responds point by point: “We have put into service over the past six years more university facilities than existed in total in 1962.”

But he has managed to elevate the debate, in terms that deeply impress the hemicycle: “I see no precedent in our history except in that desperate period that was the 15th century, when the structures of the Middle Ages were collapsing and when, already, the students were revolting in the Sorbonne. At this stage, it is no longer, believe me, the government that is at issue, nor the institutions, nor even France. It is our civilization itself.”

A sort of euphoria has spread through the hemicycle and now in the corridors. It was known how popular Pompidou was in the Assembly, not only among the deputies of the majority, but, with nuances, among those of the opposition, including the communists. His good nature, his smiling competence, his culture surround him with sympathy. It was also known that he was loved by the middle classes. But it was not known to the extent that the crisis has just revealed. His speech on Saturday exactly met the expectations of the political class. And the one he has just delivered has enchanted the journalists as much as the deputies.

He is loved for being human. He is admired for being skillful and sometimes profound. His bon vivant side is reassuring. He does not seek to constrain, but to persuade. One is vaguely grateful to him for being a contrasting complement to De Gaulle; some prefer the complement, others the contrast.

During the suspension of the session following the Prime Minister's speech, as the stream of deputies flows towards the Salle des Bronzes, I compliment him on the elevated level at which he placed his intervention. I also question him about a passage in his speech that intrigued me:

“Do you really believe in an international organization fomenting trouble in Paris?”

Pompidou: “If I said it from the tribune, it is because I have reliable sources.”

Pompidou likes to use formulas whose meaning his close associates can guess. He never speaks of the special services or telephone taps. But we know that he is attentive to the information provided by these sources that must never be acknowledged. He showed me this again at the beginning of the month, regarding the attitude of the communists.

A few days later, I learn that there is certainty of payments made to the revolutionary groups in Paris by the Chinese embassy in Bern, by the CIA, and by Cuba; not to mention some motivated suspicions on the side of Israel and Bulgaria. Always through Switzerland. “While the French possessors carry suitcases of banknotes to Switzerland,” concludes my informant, “other suitcases bring just as much to our rioters. An example of the universal circulation of cash.”

The “bourgeois” and the anti-bourgeois cross and converge. The General has aroused the simultaneous anger of the opposing forces he defies in such a high manner. But was it necessary, by accumulating challenges, to accumulate storms?

Pompidou gags Peyrefitte’s Ministry

Wednesday, May 15, 1968.

A strange atmosphere reigns in all the ministries. Everything is suspended on Pompidou. None of the ministers take the floor, nor even make decisions. They are nothing more than shadows carried along.

The impression on the public is profound: a great statesman has taken matters into his own hands. But is it healthy for all the activity of the State to be reduced to a one-man show?

Moreover, the euphoria does not last. Worrying news arrives from the West: work stoppages, sequestrations, and occupations at the Sud-Aviation factory near Nantes yesterday, and today at the Renault factory in Cléon, near Rouen.

The report that my collaborators give me on the discussions at the Sorbonne leads me to foresee a rift appearing between the leftists, who are announcing a boycott of the exams, and the worried mass of students.

I record a stern warning for several radio stations:

“The exams and competitions that will validate the academic year will be organized throughout the country according to the directives of the ministry, adapted to local circumstances by the rectors and deans. Students who do not take them will not only have lost their year but will not be re-enrolled for the following year. (...) There is no reason for the false students, who have already lost their year by engaging in politics and who have good reasons to fear the results of these exams, to force the real students to lose their year as well.”

The result of this declaration is not long in coming.

Professor Alfred Kastler has a handwritten letter delivered to me. It begins very graciously:

“M. le Ministre, you are superiorly intelligent. You have shown this at the Ministry of Scientific Research (...) and during the first year of your stay at Rue de Grenelle (...)”

It ends more abruptly:

“But what you can say now, even if one can only approve of it in essence, ruins the value of what you say, because it is you who says it. I therefore urge you to remain silent.”

I have barely received this note when Pompidou asks me to come see him: “Your declaration bothers me. Say nothing, do nothing, I will take care of everything!”

Here I am, gagged twice: by the one who has become the guarantor of the leftists and by the one who has undertaken to reduce them by appeasing them.

AP: “You see well that you should have accepted the resignation I offered you on Sunday. You would have replaced me with someone who had nothing to do with what they call ‘police repression.’”

Pompidou is slow to respond: “Don't worry. In a few days, this enormous farce will have subsided on its own, and you will regain your freedom of movement. But during these few days, I ask you to refrain from it. We are on the razor's edge. Any initiative coming from you will be automatically countered. A few days of silence, that's not so difficult! Things are moving so fast…”

AP: “If I cannot make a public declaration in the coming days, there may be an advantage to discreetly preparing what will happen next. I have prepared the decree creating a Committee of Wise Men with the Prime Minister and the Minister of National Education. It corresponds to what you announced yesterday. Here is the text, which I have signed. You can, if you approve it, sign it as well and give it to the press, to show that you are not just throwing words into the air and that you are quickly following up on your announcements.”

Pompidou takes the text, reads it slowly. I see that he hesitates when he sees that this committee will also be “with the Minister of National Education.” I specify, with a smile that must have seemed sad: “There will always be someone to assume its functions.”

Pompidou quickly recovers, as if he had been caught off guard: “Yes, yes, of course,” and he signs.

AP: “I have thought about the names of those who could be on it. I leave the student delegates' names blank, as they will be designated by the students themselves. But I have retained about twenty names, twice as many as there will be places. It's up to you to cross out the unnecessary names.”

Pompidou: “Leave this list with me, I will think about it.”

I return from Matignon perplexed. In this palace of the Republic where all powers are concentrated, it is desired that, while keeping the appearance of my functions, I do not exercise them. In this other palace of the Republic, which I am now joining, how can I maintain myself without doing anything? Rue de Grenelle needs a leader. Those who work there need to feel his presence and activity, want to know that he is taking care of them and that he will get them out of this. If I have no means to affirm my presence, I will appear like the bird hypnotized by the snake that is about to swallow it, and that no longer even thinks of flying away.

I have learned that the written instructions I sent yesterday to the rectors, asking them to affirm their presence with the deans, inspectors of the academy, and principals, have been blocked by the Prime Minister's cabinet. The order of silence imposed by Pompidou is already being rigorously applied, even to my communications with my hierarchical subordinates; moreover, it has been anticipated by the machinery of Matignon.

[…]

110, rue de Grenelle, next day, 3 P.M.

Here is the meeting of the rectors. How things have changed since the last one! They have come from their academies where the protest has established its quarters just as well as in Paris. It would be important for the minister to be able to give them instructions for the immediate future and perspectives for getting out of this situation! I do what I can to give the impression that this is the case.

I slip away for a moment, leaving the chair to Laurent, to go to Matignon to finalize with Pompidou the communiqué on the Committee of Wise Men and to propose a decree delegating to the deans the power to regulate exams, in order to allow them to negotiate their organization under good conditions. The Prime Minister refuses to give this delegation the authority of a decree.

He does not want to acknowledge, through a text that legally commits the government, that the exams will vary from one faculty to another; nor that the ministerial authority be “sliced up”; nor that a fundamental principle be undermined: the exams are the same everywhere, take place everywhere according to the same modalities, and have the same value everywhere. He is willing to have a communiqué, but nothing else. Does he think it is better to sacrifice the exam session rather than sacrifice the principle, or the fiction, of their national character? I dare not ask him the question, and, on the corner of the table, I transform my decree into a communiqué.

I hand it to him. Pompidou skims through it diagonally: “Leave it with me, it is for Gorse to read on television, so that it is understood that this engages the entire government.” So, it will not be a communiqué from the Minister of National Education, but from the Prime Minister…

Troubles spread to the factories in the West, student occupations restart

Matignon, Thursday, May 16, 1968.

This morning, the contagion reaches other Renault factories: Sandouville, Le Mans, Flins, but also Unilec in Orléans, Lockheed in Beauvais. Several of us, Frey, Guichard, Foccart, gather in Pompidou's office. The general consensus is to ask him to denounce the spread of disorder, which far exceeds the University. The positive effect of his Saturday speech has faded in three days. The public is once again feeling helpless.

The Prime Minister doubts that it is already time for him to engage again. He prefers to entrust Gorse with the task of reading a communiqué. With perfect calm, he writes, while we talk among ourselves, a text that responds to our urgings:

“As soon as the university reform becomes merely a pretext for plunging the country into disorder, the government has the duty to maintain public peace and to protect all citizens, without exception, from excesses and subversion.”

This sounds vague, while the social situation is clearly worsening and the opposition is advancing its pawns. The office of the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left has called for the resignation of the government and for elections. The Communist Party has declared: “The conditions are rapidly ripening to put an end to Gaullist power.” On the student side, the activists are seeking a relaunch. The action committees announce a demonstration against television at Cognacq-Jay for the next day at 8:30 P.M.

Frey, Foccart, Guichard press Pompidou: the communiqué is not enough. He finally resolves to speak. He always keeps the same composure and instantly drafts his speech project, which he reads to us: “I have demonstrated my will for appeasement… I have returned the University to its masters and its students… I have released the arrested demonstrators… I have announced a total amnesty… Groups of enraged individuals aim to generalize disorder, with the avowed goal of destroying the nation and the very foundations of our free society… The government must defend the Republic. It will defend it.”

Paris, same day, 8 P.M.

The Prime Minister's intervention, pre-recorded, is broadcast after a debate where Cohn-Bendit, Geismar, and Sauvageot have outmatched three seasoned journalists who opposed them. Their direct style and nonchalant expression have surely won over the audience. Pompidou's speech, following this, gives the impression of conventional language.

When students hurl insults and throw paving stones at the heavily helmeted police, it is towards them that sympathy spontaneously goes. When they invade the small screen in the face of the usual figures, they immediately dominate. In the game of subversive impudence, they will always have the upper hand.

In the evening, the Odéon is occupied.

110, rue de Grenelle, Friday, May 17, 1968.

Another meeting where I have the strange feeling of playing my own role.

This morning, I open the information days on the reform of orientation, to which those who will be, starting from the next school year, the officials responsible for orientation in the two pilot academies of Reims and Grenoble have been invited: heads of the new service, directors of orientation centers, teacher-counselors.

The audience is so surprised to hear me taking calm measures in view of the new school year that I pause for a moment to show them that they are not dreaming. They had thought that the events would engulf the reform. They are amazed that we are talking to them about the subject to which, their voluntarism shows, they are attached. When I withdraw, sustained applause from these civil servants of the National Education, who are not prone to adulating their minister, gives me some hope. There is, therefore, a contagion of courage, just as there is a contagion of weakness. But I wonder if my courage can hold out for long.

Friday, May 17, 1968.

Among my colleagues, a rebellion has arisen: “It is intolerable to see folkloric images of the General's triumphal journey in Romania while here, the insurrection is raging.”

Debré, Fouchet, and others call Bucharest to implore the General to return. He finally decides to come back on Saturday evening instead of Sunday morning.