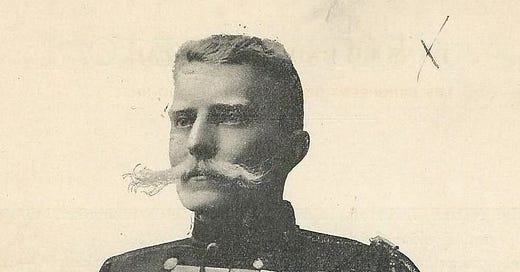

Cmdt. Charles Lemaire - Belgium & Congo (1908)

From the Almanach of the Liberal Students of the University of Ghent, published by the Association of Liberal Students of the University of Ghent

Commander Charles Lemaire was a Belgian explorer, artillery officer, as well as the Governor of the Equateur district in the Free Congo State. The following is an article he wrote for the publication of the Association of the Liberal Students of the University of Ghent.

It is an illuminating primary source on the Free Congo State and Belgian colonization. This very same article was the source used for the claims of cutting noses, ears, hands made infamous in the book King Leopold’s Ghost.

I tried many times to acquire this text only to find it was locked away in an archive, with no digital copies available. This has finally been corrected and the public at large can now read it.

Reading the article in full, we can not only see that the author of the previously mentioned book grossly took out of context those remarks, but also completely misrepresents the mission of colonialism in that era which was to speak plainly, a liberalizing mission.

Yes, Lemaire was not a hardened reactionary or some conservative stern old man. He was a Liberal. He believed the mission of Belgium was to civilize the natives of the Congo and place his own country in the ranks of modern nations. He wished to “liberate his black brothers.” Quite far off from the characterizations that are made today, by liberals themselves.

You will also see that some of the remarks made on the necessity of colonizing, such as procurement of foodstuffs, somewhat echo similar arguments made today.

Without further ado, I must also profusely thank an anonymous friend who did the hard work of physically procuring the documents needed for this post. Please enjoy.

If you are reading on your e-mail viewer, please note that this post will not appear in its entirety, I invite you to read the full text on the web.

When we put these two names together, Belgium and Congo, we wonder with amazement how, after thirty years, the situation between the two is so poorly defined. To the point of inspiring too serious concerns in those who, like the author of these lines, had given themselves, body, heart, and soul, to what they considered to be a national work.

Before asking why, of what we think of such a situation so deeply regrettable, could occur, I would like to recall that as an annexationist of the first hour, I remained so despite everything. I was more than an annexationist of the first hour; I was the first to ask, both in my lectures and in my writings, that the annexation be carried out without delay.

Here is what, in 1894, on my first return from Africa, I wrote in the Bulletin of the Society of Colonial Studies:

“It is by Diego Cam, officer of the Portuguese Navy and gentleman of the house of Don Juan II, King of Portugal, that the mouth of the Congo River was discovered, in 1484-1485. When we read the chronicles of the previous centuries, starting from Duarte Lopez and ending with the Englishman Purchas, we arrive at Stanley’s conclusion that it is a waste of time to follow them.”

“The first informations of great value were reported by the expedition of Captain James Kingston Tuckey, who, in 1816, travelled up the river 280 kilometers deep into these lands; this expedition lost, in four months, 18 of its 56 members. This disaster was the reason that, for more than half a century, no new scientific mission dared to venture in the Congo.”

“On August 9th, 1877, 999 days after having left Zanzibar, Stanley arrived in Boma: the Congo was then known. From Banana to Matadi, it offers 120 kilometers of deep waters where 3000 ton steamers navigate. From Matadi to Leopoldville, 300 kilometers almost entirely blocked by falls. Upstream of Leopoldville a navigable network for steamers, of 30,000 kilometers currently known.”

“But these 30,000 kilometers of navigable shores, to yield any value, require that railroads be built; then, indeed, these shores will find themselves, in regards to European commerce, in the same conditions as the western coast, the length of which, for centuries, navigators gather: ivory, gold, gum, resins, waxes, incenses, ostrich feathers, pepper, coffee, cacao, kola, tobacco, cotton, rubber, skins, oils, sugar, precious wood, dyewood, orcein, indigo, achiote, peanuts, rice, luxury fruits such as the ananas, of mass consumption such as the orange, animals of all sorts, etc etc… And who then could conceive the abandonment, by commerce, of the western coast of Africa?

How, then, could one hesitate to make use of the interior river network as an entirely similar operating field, currently offering 30,000 kilometers of development, whereas the Western coast of Africa, from Gibraltar to the Cape, only offers 12,500 in other words almost three times less.

Yes, the completion of the Belgian railroad of the Congo will leave a mark in the evolutionary history of Central Africa; a hundred new peoples, healthy, lively, will witness, on that day, their true initiation to honest and gainful employment, which will quickly replace the hideous slave trade, the bloody massacres, mere highlights so far of the history of these negroes.

And us, sons of a very small country in these narrow limits, we would have taken, by our work in the Congo, a place so great in the midst of the colonizing peoples, that to attack this work, and those Belgians who would have accomplished it, would become such a monstrosity that no people, no matter how strong, so forgetful could they be in political honesty, would dare place upon their conscience.

Our European independence, far from being compromised by the work of the King, as his detractors like to think, would be reinforced and assured forever by the unwavering treaties, to know the admiration of the civilized world for the realization, throughout so many dangers, obstacles and resistance, of the greatest, most generous enterprise that could be birthed by the mind of man.

And thus Belgium would no longer be able to avoid an imperious duty, the inescapable duty to take the blood of so many brave men, who died smiling, because the work of the Congo also manifests its greatness by the renewal of the devotion of martyrs.

Cato the censor had for custom, in the Roman senate, to proclaim at the end of all his speeches: “Et nunc addo Carthaginem esse delendam!” As Carthage was the irreconcilable enemy of Rome, will the Congo continue to be the enemy of Belgium? Will our conscript fathers continue to hear this gruesome shout: “And I would add furthermore that we must reject the Congo?” No, all our labor must today end by this war chant: “And I would add furthermore that the Congo must be Belgian!”

”The wait-and-see role that our generous fatherland has kept for too long humiliates us, it must cease; the hour of manly resolutions is now! Failure, turn back! And let us ensure that soon the tricolor flag tears itself with the crest of the golden star!”

It is in these ardent terms, in my belief in a purely and sincerely Belgian work, that I asked for immediate annexation, in order to furnish to an admirably beautiful work, a large base of development, stable, sure, upstanding, in a word perfect, since this was about the recognition of a child by its motherland.

Who would have thought, in that already distant time — I said that this was in 1894 — to call traitors to the Congolese work the braves who demanded annexation? They seemed, on the contrary, to be good and courageous citizens, and the anti-dynastics firmly scolded them.

It would have surprised them enough if they were told that in reality the Congolese government (that is the Sovereign) was not at all a partisan of annexation, no more than he is today in reality. Annexation has never been in the wishes of the Congolese government, and we can be certain that it is without enthusiasm that he decided to let it be proposed to Belgium.

And this is the great cause of the Congolese malaise, a malaise which could degenerate into serious illness. However, in 1896, the Sovereign had accepted that Mr. de Mérode, Minister of Foreign Affairs, tabled on the desk of our Chamber a project for immediate annexation. To what was this acceptance due? The simple fact that immediate financial resources had already been lacking; the proof, as terrible as it is irrefutable, and deeply deplorable, was provided by the revelation of the loan De Brown Detiège.

We know that in 1890 the Belgian State made a commitment to advance 25 million to the Congo State, namely 5 million in the first year of the commitment, then 2 million each following year, until 1900. During this term the loan from Belgium to the Congo was not to produce interest. However, from 1892, the Congolese Government found itself struggling with financial needs. Instead of immediately and frankly exposing its situation to Belgium, the Congo State resorts to the well-known method of sons in search of money.

It addressed a lender, Mr. De Brown Detiège, banker in Antwerp, who, in 1892, granted a loan at the rate of 6 percent per year, repayable on July 1, 1896, for 5,287,415 francs and 65 centimes. It was stipulated with the lender that in the event of non-payment on the due date, the said lender would become the owner of vast territories including the majority of the Arouwimi, Roubi, Lomani and Lake basins. Leopold II, Loukenié, as well as Manyema. This pledge represented 16 million hectares, or the fourteenth part of the territory of the State, more than five times the surface area of Belgium.

As for many acts of the Congo State, the loan made under such conditions had been kept secret, despite the clause of the 1890 convention with Belgium, which said: “The Congo State undertakes not to contract any new loans without the consent of the Belgian Government.”

And so, in 1890, to obtain 25 million from Belgium, the Congolese government undertook, by signature, not to contract any new loans without the consent of the Belgian government, the Congolese government thus obtained 25 million from the Belgian government. without interest. And two years later this Congolese government borrowed secretly, under conditions so exorbitant that there was general astonishment when, in 1895, on the occasion of the deposit, on the desk of the Chamber, of the first draft of annexation, it was necessary to reveal the De Brown Detiège loan, and to reveal it in order to obtain reimbursement from Belgium in order to save the pledge of 16 million hectares so imprudently granted to the lender.

Not only, in 1895, did Belgium reimburse the 5,287,415.65 francs to Mr. De Brown Detiège, but she had to advance to the Congo State a new loan of 1,517,000 francs, intended to cover the shortfall budgetary resources for the year 1895. We therefore see that in 1895, an annexation project was tabled on the desk of the Chamber because the State of Congo found itself incapable of ensuring its budget.

Was this a crippling defect? Certainly not. The capital error of the adversaries of colonial policy, in all countries, is to forget that the colonies are, above all, reserves set up for the future, and that it is also unreasonable to consider only the commercial profit that they immediately give directly to the mother country, that it would be absurd, when creating any plantation, to weigh the costs of clearing and planting against the product of the harvest of the first two or three years.

When struggling with financial difficulties, the Congo State should have said so without hesitation; it waited until it was forced, in 1895, to repay the De Brown De Tiège loan; unable to do so, it decided to propose annexation. A vigorous and enthusiastic campaign was waged by the annexationists; it should be noted here that they were ignorant of the true situation; they were unaware of the De Brown De Tiège loan; they ran all over Belgium to bring it to annexation, because they knew nothing of the real underside of the cards.

They were acting in good faith and complete loyalty, and served, without realizing it, shady schemes and unspeakable desires. No matter! Would to heaven that the annexation could have taken place in 1895! Unfortunately, while we were discussing in Belgium, in the Congo the sad system of rubber concessions and forced labor was developing rapidly, without brake and without control. And reports arrived in Brussels, announcing that a certain territorial leader was striving to produce, in one year, several million francs worth of rubber.

This was the signal for the Congo State of a complete change of attitude; if a particular district promised 3 or 4 millions, the same and more would be produced in several other districts; from then on the pecuniary intervention of Belgium was no longer necessary; this was surely made known to it. Without giving the real reasons for its backtracking, the Congo State had the annexation project withdrawn, claiming that there was fear of not having a sufficient majority; that Belgium should take the time to become better informed about Congolese matters of which it obviously knew nothing and more; yada yada yada.

This was the serious mistake, which would completely derail the Congolese work. A serious mistake since it based the budget on the exploitation of rubber and ivory, and therefore this exploitation — unprepared — would have to be done ruthlessly, at all costs; it was indeed a question of life and death. And it was, alas, a matter of death for thousands and thousands of poor devils, whose only fault was having black skin and not understanding what was asked of them.

I have just touched the crucial point which has dominated the evolution of Congolese management. It is important to emphasize that rubber and ivory had to be produced, otherwise budgetary expenditure would not be met. All government effort was inevitably focused on this production, and it soon seemed quite natural to only place value on people who were dedicated to production.

Their zeal was excited by the lure of monetary bonuses; this much per kilo of rubber or ivory; that much per coffee plant planted; this much for this, that much for that; thus we gave 5 francs bonus to the steamer captains of Haut-Congo for each “liberated” they transported, and arriving in good condition at destination. This is monstrous! And yet it is so.

Here is what, in 1902, I noted about bonuses in my traveling Journal: “At 5 p.m. I could take a quick walk through the station; I will first see the new cemetery which is a good twenty minutes from the center of the station. I find it installed under coffee trees, which gives them a very special look, for those in the know. I hope that we will no longer harvest, at least, coffee from these trees which are poorly suited to sheltering graves; putting a few rubber vines there would take the cake.”

“Comrade X… told me earlier that no one dared to cut those coffee trees from the cemetery for fear of observations from the Government. It is a pity that the Government cannot intervene so effectively to prevent the death of many coffee trees in the plantation for which many bonuses were affected. If those who put the money in their pockets had to hand over the premium for each coffee tree already to the devil, dead or dying, stunted, yellowish, etc… they would make a strong grimace.”

“They should have — if the bonus was so necessary — granted it only after satisfactory harvests of healthy and marketable fruit; we would then have shared the bonus between all those who participated in the work, since the planting of the prize-winning tree. In reality, bonuses only constitute a deplorable system, good for the buccaneers of commerce; when an administrative agent is good and conscientious we will, through bonuses, make him dishonest.”

“I speak of course, for the point of view, special and unique, of Congolese affairs dependent on the Congo State. Example: Here is a man who is interested in agriculture; he plants many coffee trees; but he worries about the only important point: coffee trees must be able to bear abundantly; for this you have to choose the land, take care of the plants, etc…”

“To achieve better results, we decide to promise the man a bonus of fifty centimes per coffee tree that reaches a size of 75 centimeters. So 9 times out of 10, the man puts coffee plants everywhere, since each one will bring him fifty cents. However, by directing all the work towards the development of nurseries and transplanting them anywhere; by forcing work especially through excessive recruitment of workers (men, women, children, old and young) tiring the area, we obviously manage to plant, in one year, two or three hundred thousand coffee plants, which brings in the hundred thousand francs, and more, of bonus.”

“And we offer this bait to people who are not very fortunate and who are not always in good moral health! So! So we have what we have had: deplorable results from every point of view of failed plantings because we had not identified the subsoil; agents thrown into prison when we should have loosened the reins; indigenous people massacred, and the work of colonization compromised even though it is possible and very beautiful, I have no doubt, but am more and more convinced by what I see and hear on this new journey. But the newcomers would have to be something other than complete ignoramuses of colonization and, in particular, of the history of the Congo.”

These assessments were put on paper in 1902; they could therefore not be considered inadmissible, which could have been the case if I had only written them today, for the needs of the cause that I have always defended, namely: colonization from the Belgian point of view.

And so it was the money question that dominated Congolese management, and this because the Congo State believed it could immediately find, in the colony, enough to fund its budget. The resources were indeed there, especially in the form of rubber which almost all the populations of central Congo knew, without however exploiting it.

It was from the rubber that we asked for budgetary resources at first, then sumptuary ones. To obtain this rubber, the assistance of the natives was necessary; it was demanded, covering this requirement with the legal name of tax, and forced labor was established, granting it light remuneration; the Congo State became the most terrible of tax collectors.

It is important to devote some development to the question of indigenous labor, to show what we have done and what should have been done, and therefore what will have to be done after annexation.

By penetrating in the heart of Africa, we should have told ourselves that we were going to make contact with populations for whom the word “foreigner” still meant “the enemy”, that is to say “the one we must fear and attack if we think we are strong enough.” And in the case that concerns us, the foreigner was even something completely new, unknown, legendary, therefore all the more formidable, which was called “the dressed man”, and not the white as we imagined it.

The dressed man said: “I want to carry the torch of civilization to the center of Africa; I want to destroy slavery and give freedom to my black brothers.” To do this, the dressed man was at the same time strongly armed, an excellent precaution, an absolutely essential precaution, to be able to be good without being weak.

Thanks to his weapons, a single one of which was worth hundreds of arrows, hundreds of assegais, thanks to his weapons which penetrated shields by the dozen, the dressed man, the “mo'n'délé”, could gain respect first by force. No one will dispute the legitimacy he found in making his strength felt so as not to be a victim himself.

But such essential lessons should have been exceptions, because they were only necessary to show that we were really the strongest; as soon as it had manifested itself a single time, force was to make room for kindness, since onwards it was known that this kindness was and would never be weakness.

The goodness I speak of was to consist of slowly, with extreme patience, making contact with what we liked to call “our inferior brothers.” It was necessary to set up stations responsible only, in the beginning, for living among the natives without asking anything of them, and while scrupulously ensuring that the armed servants that one would have brought with one could never worry the natives, who would have paid for any service rendered, or any product brought spontaneously.

Very quickly, — which means within a few months — the natives who saw white people for the first time, noticing that these white people did not bother them, would have completely softened. They would have come daily to the station, would have welcomed the white into their home, striving to understand him and to be understood by him. What admirable work for whites of good physical and moral discipline to gradually gain the confidence of the “savages.”

We should have paid attention to what they were doing, to taste what they were eating, without showing disgust; invite them to taste our products; walk them through the vegetable gardens that we would have created, giving them explanations about the new things that were brought out of their land; ripe fruits and vegetables, we should have gathered our black friends and offered them a taste, without getting angry if they found, for example, pineapple detestable: this happened to me when, in Equateur, 16 years ago, I made old chief Boiéra, who had had confidence in me, taste the first fruits of our first gardens.

Boiéra, the great chief of the Bandakas, with whom, in 1891, the Governor of Congo exchanged blood; Boiéra, the black burgrave who knew, in his very distant youth, Africa without whites, the Africa of legendary stories, cruel and barbaric Africa in itself, Africa of blood! Boiéra who never believed that the white man would come to his house!

And yet I had come alone, without soldiers, to visit him as an old friend. He was surprised, but didn't send me away. Soon I returned, smoking a pipe with him under his shed, sitting on benches made from pieces of canoes, the bottom of which constituted a seat and one of the back edges. One day I told him that it was his village that I had chosen to make the capital of Equateur, what we were going to call “Coquillhat-Ville”. And we shook hands, by mutual consent. He was always faithful to me, old Boiéra, who, by bonding with us in still precarious times, could compromise himself terribly in the eyes of the great chiefs of the country.

This is what those who came after me forgot, and did not think it necessary to inquire about the beginnings. I had always shown Boiéra every deference; so he was proud to see me arrive at his house, always like a good comrade, and careful never to treat him as a “dirty nigger.” What services he rendered me!

In 1902, at the start of my last trip to Central Africa, I found myself in the village of Boiéra, of my old blood brother. In his hut, never wanting to come out, crouched like in a den, living on the regret of the past! That is how I found him. In the darkness of his home — he had not wanted a house like the whites, the old chief of the Bandakas — I sat down and, from the darkest depths, called by his eldest son (to whom the white man passed, without discussion, the authority of the old chief) I saw Boiéra emerge, almost blind.

And violently: “Dikoka! Dikoka! My ally by blood! Dikoka! You! It's you again; so long! Ah! the other white people treated me badly, very badly!” And ten times the old man, in a voice still full of energy, repeats his complaint, a complaint which speaks of bitterness, regret, sadness for what is in place of what was. I give him a pound sterling, or 500 mitakos.

That's all I can do, one more beautiful gift, which I'm giving him out of my own pocket.

“How long are you going to stay here!”

“Two days.”

”Good! Will you come back to see me?”

”Yes!”

And I shake the long, skinny hand of this man who was my great friend. How all this shakes me on the inside!

Such are the impressions noted in my travel diary. I reproduced them so that people know that everything I say today is what I have said for a long time, since forever.

It was on the matter of pineapple that the memory of Boiéra came back to me, to whom I had given it a taste, and who had begun by telling me that it was not worth, far from it, a good cane sugar. I was of a diametrically opposed opinion; yet I was careful not to tell him, I was careful not to tell him that he was just a “dirty nigger” without taste.

But a few weeks later, I brought the chefs together again to let them taste pineapples, passion fruits, guavas, etc… And I started again later, so much so that one fine day the chiefs themselves planted seeds, cuttings, and shoots of our fruit species in the ground in their villages.

We should have focused everywhere on this first factor of good contact, to bring new plants and also new domestic animals, unknown to the native; thus, after a few years, a first and significant wealth would have been created in all the occupied points; important, I say, since it would have been approved by both whites and blacks.

The villages of the latter would have ended up being shaded by hundreds of fruit trees, instead of being, as they are too often, mere agglomerations of huts to which nothing attracts. Then the natives would have felt held more firmly to the ground and a stability would have been established for the exploitation of the latter which does not yet exist today.

Instead of thus acting in the interest of the natives, we were not even able to do so in the interest of the whites; most stations have little fruit; too many are without a fruit tree, and we even find some without bananas or papayas, which is as staggering as if we were talking, here, about an urban area that does not have a potato.

While introducing into the Congo plant and animal products to be consumed by both the black and the white, we would have gradually identified the forest resources, which are numerous; we would also have planted, first in the only European establishments, species whose products would have been intended for export: coffee, cocoa, tobacco, pepper, vanilla, etc., etc.

The whites should have been educators always at their task of education, explaining to the natives what these products intended for the export trade were. They would have trained the blacks in these cash crops, then, one fine day, we could have started to allocate land, along the navigable banks of the Congo and its tributaries, to families of “black peasants,” trained in us and our methods, often also educated by the missionaries whose role was here entirely indicated.

These “black peasants” would have been given not only land, but tools, and seeds. We should have taken advantage of the death of the chiefs to break up the old conglomerates of domestic slavery; and, of course, it would have been necessary to financially compensate the successors of these leaders, to justify the astonishing social change that was provoked.

The land granted by the State to black peasants should have been cultivated, partly as food crops for the farmers themselves, and partly as cash crops intended for commerce. Thus, little by little, all the points of the Congolese network accessible to steamers would have been covered with small farmers; the products of their cash crops would have been sold by them, freely, to commercial brokers.

These brokers would probably have been, almost always, more resourceful blacks, who would have resold their purchases to factories run either by educated blacks or by whites, and the State would have found its budgetary resources in the various duties of entry and exit, and in tax money. I can only lightly touch on these points of practical colonization; however I think I have said enough to establish the ideas of men of good will; to those I would say that what we could thus have achieved on the banks of the Congo and its tributaries is what exists all along the coasts of Africa: this is therefore what Belgium will have to achieve, the annexation done, if it really wants to do an honorable work of colonization, and not a contemptible and shameful work of exploitation.

We would not have limited ourselves, naturally, to giving the black peasant only the education of agriculture, we would have trained craftsmen for trades likely to be applicable in the Congo; we would have developed already existing trades such as those of the potter, the blacksmith, the weaver, the basket maker, etc., we would have trained tailors, shoemakers, brick-makers, stonemasons, carpenters, masons, etc., etc.

These workers would have been trained not only in small numbers and for the sole benefit of whites, but in considerable numbers and for the benefit of blacks as well. This will have to be done after annexation.

To ensure public order, because the black is a man just like the white, and we cannot for the moment do without the police in his home, any more than we can do without them in the realms of white kings of civilization, to ensure public order, I say, we should have to develop a local police force. For border operations only, soldiers were needed.

This crucial distinction was not made. It was not made because the leaders of the Congolese affair, implacably oriented towards the intensive production of rubber, admirably understood — from their point of view — the advantage they could draw from a blind force trained and led by Europeans imbued with prejudices that have little to do with modern contingencies.

But this force did not remain blind; it clearly saw that it could have influence; it wanted its share of the cake, it took it. Under the name of “public force”, we wanted to train troops which were comparable to the troops of our countries of “high civilization”, as the leaders of great peoples say.

“Defending the soil of the homeland is the most beautiful fate, the most worthy of envy!” We only forgot one thing: the Congolese have no homeland! From the indigenous point of view, the expression “Free Congo State” represents nothing. Boula-Matari! Good for you! Boula-Matari! Mysterious entity, formidable and feared power, emanating from afar, from an unfathomable unknown!

Who will ever say everything that has held up until now, for the Negroes, in this word “Boula-Matari” (the breaker of rocks)? “Boula-Matari” was the name given to Stanley blasting rocks for the construction of a road from Vivi to Isanghila. For several years, everyone, white and black, knew Stanley — Boula-Matari.

This prestigious name represented a well-known leader, a leader that everyone had seen. It was a time when the number of stations was limited, when contact was only made with a few natives. When Stanley left the Congolese administration, his indigenous name “Boula-Matari” continued to be used to designate those who had replaced him.

As the occupation expanded, the name Boula-Matari was used by people, white and black, who were completely unaware of Stanley. Boula-Matari, for the whites, was the sovereign of the Congo; as for the blacks, they still do not know who their sovereign is, they will always be ignorant; they do not know if he has a son who would be his successor; will they see his successor more than he saw them?

Nevertheless, in Boma the Governor is called Boula-Matari; when the Governor travels he is called by this name wherever he goes; and if he is accompanied — this happens — by a negress so-called housemaid, we call this one “Madame Boula-Matari”; sometimes the inspectors are also, by born smart blacks, awarded this high title of big shot “Boula-Matari.”

Among populations who do not have the opportunity to see Governor or Inspectors, that is to say on most of the territory of Congo, Boula-Matari does not have objectivity. Everyone forms a subjective representation of this Boula-Matari, the clearest thing for the natives being that he has many men armed with rifles that they cannot have.

Boula-Matari is the indisputable power in whose name everything is done, everything is asked, everything is imposed. Boula-Matari rings, in the ear of a black, a bit like the words “the Government,” which has gendarmes and to whom we must pay tax. But we must increase tenfold, a hundredfold the impression produced.

For the native, the name “Boula-Matari” has become a generator of terror, so many crimes have been committed in the name of “Boula-Matari.” When Belgium is master, free and complete master, of course, of the destinies of the Congo, the first thing that must be done is to forget this name which strikes terror into the heart of the native.

Never, anywhere, should we recall Boula-Matari again, except to say: “‘Boula-Matari’ that’s over!” Let no one accuse me of lèse-majesté! I repeat that “Boula-Matari” in the minds of blacks does not apply in any way to the Sovereign whom they do not know, whom they will not know.

When we tell them: “Boula-Matari” that’s over! that will mean: “You will be treated differently.” Because they will have to be treated differently; gain their trust; slowly extinguish the justified hatred they have for the whites of Boula-Matari. And it will take years! Years which will require financial sacrifices from Belgium.

Belgium will know how to do them, because justice which repairs is the mother of prosperity which rewards. To concretely show the natives that “‘Boula- Matari’ that’s over!” it will be necessary to understand as soon as possible that the military organization of the public force cannot be maintained. The Congo needs police officers, field guards, gendarmes, forest guards. Soldiers would never have been needed, except, I said, for border operations.

It is appropriate to declare that nothing is more noble than the profession of soldier, which does not prevent it from being entrusted in more than one country of high civilization only to those who have not enough money to escape this noblest profession. Yes, defending your country is the noblest act there is! But the implementation must match the words.

And I imagine that more than one of our brave militiamen is of my opinion, and hardly understands that the homeland demands such great sacrifices from it, while so many favored by fortune only give to each and every one the most pitiful examples. Little soldier you will be the palladium of your country! We will train you harshly for this noble role.

And, during this time, the little rich will too frequently form a virulent ferment of national demoralization. The soldier — simple pioupiou or officer — who believes in his profession is an admirable man; he has the highest moral qualities there are. But could we make such soldiers from black people from central Africa?

Were we going to talk about the soil of ancestors to slaves, delivered by their leaders to Boula-Matari to make them soldiers? These slaves didn't even have a village! These slaves had no tribe, or they had too many, because sometimes, on a certain ebony face, tattoos of three or four tribes of which the tattooed person had successively belonged were superimposed.

It is to these very rudimentary elements of social organization that we turned to make “modern soldiers,” soldiers who would know what it is to defend the homeland (in this case Boula-Matari), soldiers steeped in self-sacrifice, devotion, respect for their venerated leaders, venerated because venerable. I say “venerated because venerable” because if we want authority to be respected, it is necessary, isn't it, that it must keep itself respectable?

The Congolese soldiers would be given flags, and as a result, they would have a sacred attachment to them. They would be given uniforms, and as a result they would acquire self-respect and a sense of military honor. They would be served with military marches, and as a result their hearts would swell with bravery and patriotic enthusiasm.

We would carry out reviews, we would fire the cannon, we would distribute shooting prizes, and so the Congolese soldier would become a model. And how much the Congolese soldier had to be looked after! Bah! common civilian worker! Colonizers aiming at the development of the country for its own sake as well as in their own interest would undoubtedly have believed that the civilian worker deserved at least as much consideration as any other element.

The Congo State Government did not share this opinion. Here is what we read in the “Instructions” for its public force.

“Agents must make every effort so that our troops have, among the blacks in the service of the State, a privileged situation and, to achieve this goal, the soldier must be in a more advantageous position than the civilian worker, by his accommodation, his food, and time devoted to work.”

Having thus specified how we should promote — we wonder why? — the soldiers, the same instructions add with candor: “Where the soldier is placed in these conditions, he will attach himself to his leaders and we can count on him.” Ah! he understood well, the Congolese soldier! Better housed, better fed, less work! And with that a white man’s rifle! A uniform and stripes to mark your social superiority!

By adding to this some small privations to the detriment of the civilian worker and his wife, and many large privations to the detriment of the vulgar “wachenzi or ba-ou” (heathen of the Congo) and his wives, we understand that the Congolese soldier has taken a liking to the profession. After the advantages reserved for him by the instructions on the public force, he had the advantages which he reserved for himself.

He became the master of situations, had terrible revolts when the famous qualities of the modern soldier were demanded of him, and made people count on him everywhere. And too many white people know this advice: “You should not pay too much attention to soldiers, because between arguments you could catch the first bullet.”

After all, no one is surprised that I sometimes had to write to the government things such as this: “War! these abominable acts of bandits! Everything that is great and beautiful about modern military spirit has never, or very little, been known in the Congo.”

During the mission that I led in Bahr-el-Chazal (mission of which the state of Congo would not dare to publish the exact and complete history) I had to write lines such as these, dated Saturday 7 November 1903: “It is time, if it is not already very late, to completely overturn the current organization of the public force; Above all, the atmosphere of spinelessness and cowardice in which white people live today must be dissipated, which explains why they give free rein to bandits who are very improperly described as soldiers.”

“It is necessary, whatever sacrifice the Government must resign itself to, that the numbers of the public force be reduced, and that we regain in quality everything that we allowed to be lost in the belief that quantity would be enough.”

“The era of optimistic reports must end, and harsh truth must be heard. I will never tire of repeating it, even if it cost me everything, position, financial and honorary advantages, etc. I am perfectly aware of the seriousness of my statements; I also have a perfect idea of my responsibilities, both direct and indirect.”

“And finally I see a much more beautiful, much more good thing to do than what was done by so many agents of whom only their reports to the Government were always satisfactory. The Government, with these false reports, naturally had to err. Those who believe that they are only invested with its confidence in order to respond to it at all costs, have the imperative duty to speak as I speak! Do what you must! Come what may!”

These were the warnings that I gave to the Congolese Government about the spirit of its public force; and yet I knew and I announced what it would cost me, what it cost me.

In the June 15, 1907 issue of the “Movement of Catholic Missions in Congo”, Father David Steinmetz recounts a journey by canoe in the Arouwimi. Here is what we read in this sincere story: “Boumbwa is one of the largest villages in Arouwimi and perhaps in all of Congo. When I arrived, everyone is at attention.

We arrive to the song of paddlers who repeat this refrain: “Here comes the father. This is no ordinary white. He doesn't come with an Albini to kill men. He does have a rifle but it's for killing birds. Here comes the Father. We paddle a great man. Sweep his house; bring wood to make his fire; bring water; bring chickens and eggs.”

The Father settles down and makes a series of recommendations to the blacks. “And you, men, you must also work for the Boula-Matari (white of the State), paddle well, and he will be happy with you, and he will not put you on the chain.”

The narrator writes again: “A little later one of my chickens flies into a tree; I quickly took my rifle, and the pellets immediately shattered his head; and the blacks sing: ‘He is a great man who knows how to shoot well, he is certainly a commander!’”

Are these indigenous songs not of a psychology that is both interesting and terrible? “A great man who knows how to shoot well is certainly a commander, who has an Albini to kill men.” It was this education that was given to me when I first started out in Africa 18 years ago, by the senior officials under whose orders I found myself. I was 26 years old then.

As preparation for African life, just reading the few rare works published at that time for me as for everyone else, Central Africa was nothing but a land of terror. My mind was ready to accept the words of our “elders”; this is how my African education began in rifle and cannon fire; in the burning of villages to be “brought to reason”, in a word in the abuse and over-abuse of brutal force with all its excesses.

I became a leader myself too; for a time, I followed the examples received, then, little by little, I came to doubt the excellence of our processes; I reread my first reports with horror; my entire being pulled itself together; I swore to myself to devote my efforts to the black race; I promised myself to say and repeat the reasons for the misunderstanding which has covered Africa with so much innocent blood.

It took me four years to open my eyes to reality. From then on I never stopped defending the negroes, I tried to show their qualities; I highlighted the results obtained by missionaries of all faiths. And when I returned to Africa I was certain that I would never kill again. And I didn't kill anymore. I made two long crossings across the whole of Africa without burning a single war cartridge.

But I became merciless towards the soldiers whom the rubber regime had rotted; I imposed on them something of which they had no idea, and that was respect for the native. It was from the soldiers' wives — women often corrupted by the whites themselves — that this respect was often hard to obtain.

I only achieved this by applying punishments that have now become extra-regulatory, but which had, for many years, figured in state regulations. I did not apply, during my military mission in Bahr-el-Chazal, any punishment that had not been applied by all the officials indiscriminately, including those who found there the means to finally strike me, with all the loyalty and all the courage which are the mark of a good Secretary of State, in one or several people.

To stand up to the bandits who constitute the current public force of the Congo State, and to ensure respect for the native, I did not have the variety of means that we have in organized stations; I only had the means available to a military leader lost in the bush. I had to choose either the whip in an extra-regulatory dose (that is to say 50 lashes instead of 25) to all those who deserved it, or bringing fire and blood to the country under the pretext of military conquest.

I chose extra-regulatory punishment, thanks to which not one violent death of a man can be blamed on us. In 20 reports I warned the Congolese Government, citing concrete cases, emphasizing the inevitable necessity for me to take justice myself. Never was an observation addressed to me; I was always lavishly congratulated.

I come back to what I said earlier, to the fact that after the essential recovery of the Congo by Belgium, the name of Boula-Matari should be forgotten and radically forgotten, immediately if possible. We will replace it with these new words “Belgium”. Likewise, the State’s flag must give way to our tricolor flag.

Finally, the uniform of the public force will disappear or at least be profoundly modified: the public force will be brought back to its true logical, useful, and indispensable role of gendarmerie. And black law enforcement officers will be workers at the same time.

On the other hand, recruitment will be localized; volunteers will serve at the very place of their commitment; we will no longer see people recruited around Boma sent to Tanganika and vice versa; by leaving them at home, and in charge only of the local police, we will at the same time put an end to three quarters of the abuses coming from the current public force.

This institution will once again become what it should always have been, a school where we will train elements destined to return at a given time to their village after having acquired various labor knowledge, and having become accustomed to the consumption of new products.

The Congolese Government considered it a good policy to disorient its soldiers; people recruited in the South were sent to the North, those from the West were sent to the East, and vice versa; moreover, any detachment always had to be composed, in equal proportion, of men of four different origins. It was thus intended to prevent rebellions by opposing divergent interests; we hoped to have a force incapable of doing anything other than obeying. We know how wrong we were, we know that terrible rebellions occurred, among others that of the fort of Tchinkakassa, cover of Boma-capital, as it is said as pompously as naively.

When, after the Tchinkakassa revolt, a certain number of “rebels” were condemned to death, people wondered if the firing squad would not turn its guns on the “authorities” attending the execution. And, to guard against such a fearsome eventuality, all agents of the State were made to attend the execution in Boma, formed into an armed platoon which was placed in a long line behind the platoon of black executioners.

About sixty whites formed this platoon deemed necessary to force the black soldiers to shoot at their comrades of yesterday, instead of shooting down the “authorities” attending the ordeal. Does the rubber Government believe that we have such security platoons everywhere to keep current soldiers in obedience? My agents and I kept our soldiers in line with the only whip they deserved for their misdeeds.

While the instructions of the Government prescribe to the whites to only present themselves to the troops with the revolver at their side — in order to shoot down on the spot any leader of mutineers — mine defended the port with revolvers.

And we have had no revolts; we reduced to a minimum the nuisance of the Public Force (which the State had provided to me to occupy the territories disputed to England), without shooting down a single rebellious man like putting down a rabid dog.

Let public opinion decide between us and the Government who, in Boma-capital, needs such a deployment of armed whites to ensure the execution of its Law and the decisions of its Justice.

Returning to local recruitment, of which I speak of from personal experience, the Congolese Government, I repeat it, will suddenly put an end to three-quarters of the abuses caused by the current public force, rotten to the core in the exploitation of rubber by forced labor, under the guise of legal appearances.

Finding themselves at home, the black elements of the public force will no longer engage, as now, in organized marauding; they will no longer terrorize populations instead of protecting them; When their term is over, they will return home and bring something new to their villages, provided that their leaders know how to take effective care of them, other than just during the occasion of so-called military exercises.

And we will stop the development of a danger that has become formidable, a danger constituted by the current agglomerations of former soldiers who lay down the law in many white stations of the State.

I have dwelt at some length on the question of public force because it is perhaps the most important factor to examine in all Congolese questions. I will now quickly review a series of other factors.

COLONIAL SCHOOL

In 1894 a group of what were then called “The Colonials,” people enthusiastically involved in Congolese work whose underlying aspects remained unknown, decided to create the “Society of Colonial Studies” whose aim was to popularize the Congolese question.

This Company was to have its main headquarters in Brussels, and branches in the main cities of the country. The promoter of the “Society of Colonial Studies,” was the late Mr. Couvreur, member of the House of Representatives.

By joining Mr. Couvreur's call, who among us could have imagined that we were going to seriously worry the State of Congo? Who could have thought that the “Society of Colonial Studies” was going to be treated — sneakily — as a dangerous organization, by the very people we intended to help, that is to say by the Congolese Government. I can still hear the tone in which the Secretary of State asked me personally: “What does this ‘Society of Colonial Studies’ want? What do these people want to involve themselves in…?”

Now that the truth is becoming clearer and clearer on the shady activities of the Congo State, we understand that it has taken a dim view of creation of a Society which claimed to enlighten the nation on the Congolese problem.

Unfortunately for the “Society of Colonial Studies,” its founder, Mr. Couvreur, died a few months after the creation of the Society, and so the Congo State maneuvered to get its hands on the direction of this Society; it skillfully had a very eminent president appointed but who, given his numerous occupations, could hardly play the active role that Mr. Couvreur had played; to replace him in this active role, a vice-president was appointed who, without realizing it, was the toy of the State, just as all those who believed they were serving an honest work and went there in good faith were the toy of the Congo State.

And yet the Society of Colonial Studies was able to create a colonial school in its midst whose teachers were former Congolese civil servants and officers; this corps of professors wrote an excellent work entitled: “Manual of the traveler and resident of the Congo.”

On the subject of this manual which was to be written by a group of Congolese, the Congo State shrugged its shoulders, laughing at the idea that we could find any agreement between Congolese.

Yet the manual was made; and the Colonial School opened in the premises of the Society of Colonial Studies in Brussels. This happened almost 14 years ago. We had asked the State to allow its new enlistees to follow the school’s courses. The State did not dare refuse despite its strong desire.

It allowed a class of agents destined for Africa and already engaged to follow our courses, which lasted approximately two and a half months. But when we wanted to open the second session of our courses, not a chance! No one in sight. The state had immediate need — it claimed — of all those it hired.

And the first Belgian colonial school collapsed as soon as it was created. Since then, the State has replaced it in its own way. It created in its offices a “colonial course” of which, the 3/4 of the program was disconcerting, especially vis-à-vis of the teaching given by the Society of Colonial Studies.

So much so that after thirty years of colonial growth we are still waiting for a colonial school. It is very true that we are promised a world school; we laid the first stone two and a half years ago; we appointed a wonderful commission which developed a wonderful program.

While waiting for the actual achievements — if they are ever to be made — the Belgian nation is as ignorant today of true Congolese knowledge as it has been since the beginning of the enterprise. To delay the annexation they said: “The nation is not ready. She knows nothing about the question; you need to give it time to research it.”

Well! I ask it of people of good faith! What do Belgians know about the Congo? I answer: “So little as nothing.” I find the unfortunate certainty of this in requests for information which reach me every moment, from young people wishing to go to the Congo; one asks me in what conditions we are housed; another if we must not fear wild animals; a third asks what we have to eat; a fourth how long it takes to get to the Congo. Thus, even these very elementary details are unknown to the vast majority of Belgians. What then to think of questions, infinitely more serious, such as the laws of modern colonization, relations with the natives, complete knowledge of the rules of European life in the Congo, etc…

Annexation was delayed under the false pretext that the nation was not ready. This implied that we would prepare it. To prepare it it was necessary to support and develop the Society of Colonial Studies; the Congo State was content to put it to sleep or, better, to hypnotize it while using the financial resources of the said Company to create, in the Congo, a superb bacteriology laboratory. We had thus found an excellent derivative for the Society of Colonial Studies, whose Bulletin is barely known in Belgium, even though it should have been distributed to all schools and public libraries, provided that a detailed review was carried out of the real Congolese situation, considered from all points of view.

To prepare the Belgian nation for the resumption of the Congo we should have supported the first Belgian colonial school; the Congo State preferred to no longer provide it with students; then, it replaced it with its own school, where we are mainly concerned with the study of Congolese military regulations, the way in which rubber is packaged so that it does not become sticky, the slips to be drawn up in case of damage to the goods for the proper intervention of the insurance companies… etc… etc.

To prepare the Belgian nation to take back the Congo it would have been necessary to use the Press, by providing it with copious extracts from the reports of both travelers and civil servants of all categories; by providing it with all the elements which were accumulating in the State archives and which will probably no longer be found; by enabling it to provide the country with all the elements of discussion necessary for a free and honest nation.

We know how the Congo State treated the Belgian Press. When in his office, in January 1906, the Secretary of Foreign Affairs of the Congo, said to me, regarding my withdrawal from command: “The press will not speak,” he was giving proof of the harmful action that the Congo State exercised over too many Belgian newspapers, some by simply corrupting them with money, others by abusing their trust and compromising them, without them suspecting it, to such an extent that today it would be impossible for them to be anything other than sycophants of the Congolese system.

So much so that the Press, which should have been used to document the nation more and more, was reduced either to intoxicating it, or to leaving it ignorant of the realities of the Congolese affair.

And this is how we are faced with this ridiculous situation: a House of Representatives, a Senate, a Belgian Ministry as profoundly ignorant of Congolese realities as the rest of the nation.

And this Chamber, this Senate, these Ministers are seized of a colonial bill and a recovery project. This must give them all great cause for shock. Is the Congo State itself, at least its central government based in Brussels, aware of Congolese realities? What does he have to know them? The reports from its African officials, who will be careful not to provide the optimistic reports expected.

The sovereign being unable to deal with the Congo as it is, since he has not seen it, must be content himself with treating the Congo as he wants it or imagines it to be. He found in his Congolese staff — apart from a certain number of exceptions — all the flexibility required to establish what I will call “a subjective Congo.” However, Belgium must know “the objective Congo.”

And for this we need immediate, active, highly developed colonial education, starting in private schools. mayors and lasting even in universities. I cannot deal in depth with this very important question. But here is what I already wrote in 1894, about the Congolese exhibition in Antwerp.

“During the course of the Exhibition several requests for reduced collections were made not only by Belgian establishments, the Higher Institute of Commerce in Antwerp, for example, but also by foreign establishments, the National Museum of Ethnography from the Netherlands, to Leiden; the Greiz Commercial Museum (Germany), etc…

“This interest from foreigners is significant, will we be able to commit as soon as possible to the path it indicates and to make the Congo known in all our schools, higher, middle, and primary, by means of reduced school collections, such as those requested by Germany and Holland?”

“The Congo known to children will then be a little more familiar to parents. So get to work!”

So get to work! By this I meant that the State of Congo was going to place reduced collections in all schools, relating mainly to the ethnography and economy of the Congo. Teachers wrote to me. I addressed their letters to the Congolese Government. Well! Is there a single official school in Belgium that received these reduced collections from the Congo State? None!

If, in some private educational establishments, we find superb Congolese collections, we owe it to individuals, not to the Congo State which had many other fish to fry.

So that everything remains to be done for the colonial education to be given both to those who remain in the country and to those who go towards the unknown, the formidable unknown, the land of terror which, unfortunately, always is, rousingly and unnecessarily, Central Africa.

I say that we need colonial education for those who remain in the country. We would start by telling them that good preparation for departure to the Congo does not consist precisely of weddings and feasts, as it is still understood today.

To cite a personal case, I remember that on one of my returns from Africa I was celebrated for two and a half months by excellently intentioned friends, who all offered their guests oysters, woodcock, pâté de foie gras.

As the end of this rather Belgian regime approached, we learned that a mutual friend, who had participated in all our back-to-school banquets, had to leave in turn; quickly we organize a new series of banquets where oysters, woodcock, pâté de foie gras reappear formidable, implacable, inevitable

This lasted another two and a half months. After which I had the idea of representing with a diagram the gastronomic celebration that friendship had organized in our honor and for our pleasure. This diagram took the form of two little men examining a sort of composite monster whose legs were made up of more than a hundred baskets of oysters superimposed; the body, from a block of Colmar measuring several meters; above it a woodcock's head whose beak went from Gare du Nord to the Gare du Midi.

In truth, when someone leaves for Africa, he should be considered to have left a month or less before the date fixed for his real departure; thus we would leave him entirely to his preparation and to the effusions of his loved ones, effusions which, usually, are poorly marked by banquets.

Likewise, when people return with spoiled stomachs, it is cruel to impose on them the regime of banquets which are especially honored by those who invite, not the guest.

We would still tell those who remain in the country that they must write regularly, with each letter, to relatives and friends who are in the Congo; that nothing is more painful for the exiled than to see the mailbags arrive without anything coming out for him; that this gives a dangerous feeling of isolation, whereas he should be kept connected to us.

We would say that you shouldn't write this:

“MY DEAR SO,

I am writing you a few brief lines to show you that you are not forgotten; however knowing that other friends make it their duty and pleasure to give you all the interesting news from here, I do not want to duplicate and am content to wish you good health and best wishes.

Your devoted,

Χ. Υ. Ζ.”

We would teach parents and friends of the Congolese how to pack a bundle of newspapers so that it resists transport that the postal services of civilized countries do not experience. We would tell them for example that it is not enough to write the address on the edge of the newspaper itself as one can do, without inconvenience in Belgium.

We would recommend not waiting until the day before the boat leaves to start gathering the newspapers to send to the white Congolese. I have often seen packages of newspapers arrive, each newspaper bearing the same date, the date of the day before or two days before the boat's departure. Those who made these shipments had neglected to keep the complete collection of a single newspaper; to make up for it, they sent all the newspapers from the same day: but, especially when it came to a white man lost in the Congo, when he has read a gazette, he has read almost all of them.

We would also say, how to make a postal package, what to put in it so that the shipment has little chance of arriving entirely spoiled.

How many times have I seen postal packages opened with bearded cheeses, deliquescent Antwerp fillets, tobacco flavored with anisette following the breakage of a bottle that had been believed to be wonderfully protected by the tobacco itself, etc, etc.

Above all, we would say to parents: “Don’t ask your children for extraordinary stories. Don't excite them into sending you tales of thrilling adventures.”

To take an example, we continue to imagine that a Congolese worthy of the name must have massacred many buffaloes, elephants, leopards, lions, rhinoceroses, etc. So we find it natural to receive, from the son who left for the Congo, photographs where, with his rifle on his thigh, the “little one” is boldly seated on the top of the enormous head of some monstrous elephant. And the family is ecstatic! “Do you see that! Joseph! What a hunter he has become! Would we ever have believed that?”

Yet it was not Joseph who pulled the elephant. These are his black hunters. His role is simply to arrive afterwards and have his photo taken in good posture. He sends the photograph; in return he receives congratulations, explosions of admiration. We tell him that we showed “the glorious photograph” to all friends and acquaintances, that we are proud in the family.

And Joseph ends up believing that it is indeed he who has become a Nimrod di primo cartello.

He gets used to imposture… to please parents, friends and acquaintances. Soon he spices up his stories; he lives among indomitable cannibals, which his energy alone maintains in obedience; he gets drunk, he dreams of shootings and assaults on villages, in order to write to his family “the story of his exploits.”

And it provokes, if possible, the opportunities to make the powder speak. Well, those who live in Belgium should be taught that the entire Congolese existence must take place peacefully, without almost any sensational events. Parents should be accustomed to being content with the detailed account of the very ordinary life that one can lead in all Congolese stations; to give their stories interest — and a more serious interest — the Congolese should closely study the indigenous mentality, they should observe these “so-called savages,” and they will be amazed at the pleasure they will discover in noting how these so-called savages know how to think, and show a spirit of reflection.

An example: in one station we were raising a hot air balloon. Many blacks from the surrounding villages attended the ascent; among them a leader who is notified at a given moment by the white, commander of the station; this leader hardly looked at the balloon which was held by means of a rope.

“Well!” the white man said to him, “does this not interest you?” To which the “savage” responds: “Isn’t it the wind that makes your “machoua” rise, like it makes dead leaves rise? But tell me, how do the white people manage to make a hole in this needle?”

And the savage presented the civilized man with a needle found in the station. His attention was much more focused on this needle than on the balloon; in fact the blacks use as needles, first simple natural thorns, then wrought iron rods, thinned as much as possible, and provided not with a hole but with a simple oblique notch in which the thread is pinched.

And so upon seeing a European needle, the savage was keenly interested in the hole, so small and so clear, in this “civilized” needle. The white man he questioned did not know how to make a hole in a needle; he had never worried about it. And the black man's request must have provoked long and interesting reflections for him, an excellent subject for a good long and interesting letter to his family.

And do believe that African life offers every day an opportunity for exercise for observing minds. I hope I have said enough to show the need for a truly special colonial education to be given to those who remain in the country. They should also be given an education partly in common with that which those who leave must receive; the various points covered by this entire study bear this out; I will therefore not dwell further on this.

As for the colonial education to be given to those who leave, it must aim to enable them to acquire what I would readily call “preliminary experience.” This is why this teaching must be given by teachers who “have practiced” before professing. Whether it is a question of teaching, in a colonial school, botany, medicine, or cartography, I say that one will never make more than a poor teacher if one has not first lived several years of colonial life. I am certainly not saying that this condition is sufficient; I say it is necessary.

It would take me too far to develop the program of colonial education here; However, I want to draw attention to a crucial point: we will have to imbue young people who are going to expatriate themselves with this notion that absolute respect is due to everything we see, everything we hear abroad.

Whatever we see, whatever we hear, we must never express the naive astonishment of the gentleman who has never left his village, or even his province, or even his little Belgium. We cannot emphasize enough this point which dominates the making of contact between representatives of different nationalities and races.

If colonial education inaugurated, as I recalled earlier, by the Society of Colonial Studies, had been supported and developed, we would not worry today about this vaudevillesque situation of not having still as “Ministers of the Congo” only two Ministers of State, Misters Van Eetvelde and Descamps David, barons who have never seen the Congo.

We would certainly have them; but next to them we could think of Congolese ministers who have practiced; we would have in the Chamber “colonials” who have seen instead of “colonials” who must speak well only by hearsay; in a word, we would have enlightened the nation which, it was claimed, really needed it before making the annexation.

And the Belgian and Congolese governments would have more leaders who could be said to be: “right men in the right place.” We would have, for Congolese Belgium, lasting men such as the Lords Cromer, the Curzon, Kitchener, the Reginald Wingate, etc. These men are the pilots having before them a clearly assigned goal; in the Congo we still had, apart from one exception, only aimless pilots; and this is why, while a Lord Cromer ruled Egypt for more than thirty years, I have known, in the Congo, in only 18 years, 9 general governors.

How can we be surprised then that in reality, and despite self-serving assertions to the contrary, the Congolese work is without stability, without security, and always full of trial and error.

The question of the education of blacks is linked to the question of colonial education for whites. As I have said, the Government will find the most valuable support in missionaries of all categories, provided that it comes to an agreement with them for the application of a specific program of practical teaching. It goes without saying that the Government would not have to worry in any way about the religious side of the teaching of missionaries.

The goal to be pursued here is, as I have explained, to train families of black farmers capable of working on food and cash crops, farmers who would receive land along the banks of the Congo and its tributaries navigable by steamers.

It was proposed to send to the Congo repeat offenders who are not doing well in Belgium. We have always protested, with all our strength, against such a proposition.

It has been repeated enough that the major part of the Congo cannot be a settlement colony; however, the condemned, or the unfortunate people accidentally withered, can only think of creating a new era of honor and work on condition of leaving their country for a long time if not forever; and if they have to leave their country it is to escape contact with their compatriots. However, sending them to Congo is not to withdraw from this contact but to accentuate it, to highlight a situation that they wish to hide and change; and frankly the conditions of struggle in the Congolese colonial work are already harsh enough in themselves for us not to bring into Africa (until further notice at least) an element which seems to be lacking in the strongest force of resistance, I mean healthy, unscathed, well-tempered morals.

The pioneers of the African work must be able to stand shoulder to shoulder in comforting contact. Could we make such contact with people forced into exile? Any idea of deporting to the Congo either convicts or vagabonds accustomed to penal colonies is deplorable and depressing.

In their “Hygienic and medical guide for the traveler in Central Africa,” doctors Nicolas, Lacaze and Signol write: “In Africa, moral energy must be based on unfailing physical energy” (2nd edition, page 373).

Are these conditions realized, or even achievable, by vagabonds or the condemned, or even by the unfortunates destroyed by accidental setbacks or others, disgusted with life by heartbreaks, etc? However, at regular intervals, the idea of sending all the bad outcasts from Belgium to the Congo comes up again in the press.

Here is what I read, for example, on this subject, under the title “Les casquettes grises,” and about repeat vagabonds: “There would indeed be something to do; change the law, rid ourselves once and for all of these professional criminals, by permanent internment, or deportation to the Congo, where perhaps they become honest people again, contrary to so many honest people who there become something completely different.”

Based on this point of view, another newspaper sponsored the idea of attempting to send convicts to the Congo who would be subject to conditional release. And as proof of possible success, the newspaper cited the case of the English “convicts” who, a century ago, were deported to Australia, and thanks to whom this colony developed marvelously.

To retort this proposition it suffices to remark that Australia was a land of settlement where the English “convicts” were sent away forever; whereas the Congo is an exploitation colony where the European can only make relatively short stays. You should also know that the convicts were treated as truly white slaves, and that this era no longer has this system.

It must also be said that, from 1853, deportation was stopped for all of Australasia, and that a large party, called the “Emancipists,” demanded at the same time, in Tasmania, that we cease to deport convicts there.

Here are also some extracts from special publications, which will finalize the solution to be given to the idea of sending repeat offenders or other convicts to the Congo:

1) The report addressed to the President of the French Republic by the Minister of the Colonies regarding the application of the law on relegation to the colonies during the years 1891-92-93 demonstrates, once again, the ineffectiveness of the legislative measure on which, eleven years previously, its authors had based such brilliant hopes.

This experience of eleven years should be enough and the only course to take would be to repeal this law, which does not protect the mainland and which is an unproductive burden for the colonies, and even harmful with regard to New Caledonia, by the obstacles it opposes to the full development of free colonization.(Extract from the Quinzaine coloniale published under the direction of Mr. Joseph Chailley-Bert).

2) At the Australian Federal Council the fear of seeing the New Hebrides archipelago was expressed; in the possible event of it being annexed by France, becoming a penal colony in the latter's hands, which would create a dangerous, unbearable neighborhood for Australia.

3) Certain articles in the Parisian press having argued that the settlers of New Caledonia were keen on deportation, the President of the Federal Council of New Caledonia sent the following telegram to the “Colonial Policy”:

“Please deny false articles representing former settlers of New Caledonia as friends of the penal colony. The general council still calls for the elimination of transportation.” (Signed) Lecomte.

These are enough competent opinions to give pause to those who think they have to thoughtlessly republish the idea of deportation to the Congo. It must be a chapter of theories to be taught at the Colonial School intended for those who are not to go to the colonies.

For my part, I believe it necessary to employ elite elements in the colonial management, elements of which the nation has reason to be proud, and who can inspire absolute confidence through their honesty, their disinterestedness, their moral and physical discipline. In a word, we must only entrust the work of colonization to people capable of being “models,” of being what Wells, in his “Modern Utopia”, calls “Samurai.”

But if I condemn any sending of “social no-value” to the Congo, I make it my duty to point out a category of people who could occupy the positions of white artisans in Africa, in very satisfactory conditions of morality, and physical and moral resistance. I am talking about orphans.

One of the greatest sufferings of those gripped by illness in Congo is the memory of family, of old parents; we face danger better when we only think of ourselves when encountering it, and not of the father, the mother who wait anxiously, at home, for the beloved son to return to their arms.

Therefore, could we not think of sending to the Congo both as workers entering into contracts with the Government, Companies, industrialists, etc, and as independent workers, workers leaving orphanages, as soon as they are of the appropriate age to face life in the tropics?

And who knows if more than one would not follow the example given by honest Europeans, such as Captain Joubert in Tanganika, such as the late respectable Protestant missionary Grenfell, still others who took a legitimate black wife, and had many children.

There is still a category of whites who could, by finding their own interest, render very special services to the colony; just as our young officers go away for one or two three-year terms, give blacks military education, similarly our young teachers could go and do one or two terms in the Congo, be employed there, part of the day, on various station jobs, and another part of the day giving blacks education, as we advocated earlier regarding missionaries.

These young teachers would thus train themselves for a practical life, make a little money, and take their place in the teaching corps just as officers take their place in the army; and as for the latter, we should preserve all their rights to advancement and seniority. Having acquired special knowledge, they would reappear before their students with the prestige of men who have seen, who can say: “I was there, such a thing happened to me!”

So far I have talked about those who leave. It's good to also dwell on the returnees a little.

For them again, a special section of colonial education will be necessary; we will tell them that it is by no means necessary to have a big wedding party to prove that you are a man.

We will show them why they must carefully keep their money safe, so as to ensure, after 18 to 20 years of colonial existence, sufficient resources, forever protecting them from want.

To give you an idea, here is a calculation based on the payment conditions that the Congo State currently makes to its agents. Consider a young man aged 23, with the education of a good non-commissioned officer, or a clerk.

We will follow him in his career, not assuming it to be particularly brilliant, but rather ordinary, as a worker not gifted with exceptional intellectual faculties can see it develop.

The man commits to 3 years for an annual salary of 1500 francs; all expenses will be paid, including return travel, accommodation, clothing, servant, food, travel.

He could therefore, in a pinch, not spend a penny of his 1500 francs of annual salary. But I do not I don't want to impose on him the deprivation of the small pleasures of life: tobacco, newspapers, glasses of beer, purchase of collections, etc. And I will assume that our man spends 1/3 of his salary on this.

When he returns to Europe, his 3 years finished, being 26 years old, he will have 3000 francs. The State does not yet regularly allocate leave pay; let's assume that our young man will have to take on his 3000 francs to cover his expenses during his six months of leave; he will spend 2000 francs per example.