The following article is written and generously provided to us by @LCbtPndD

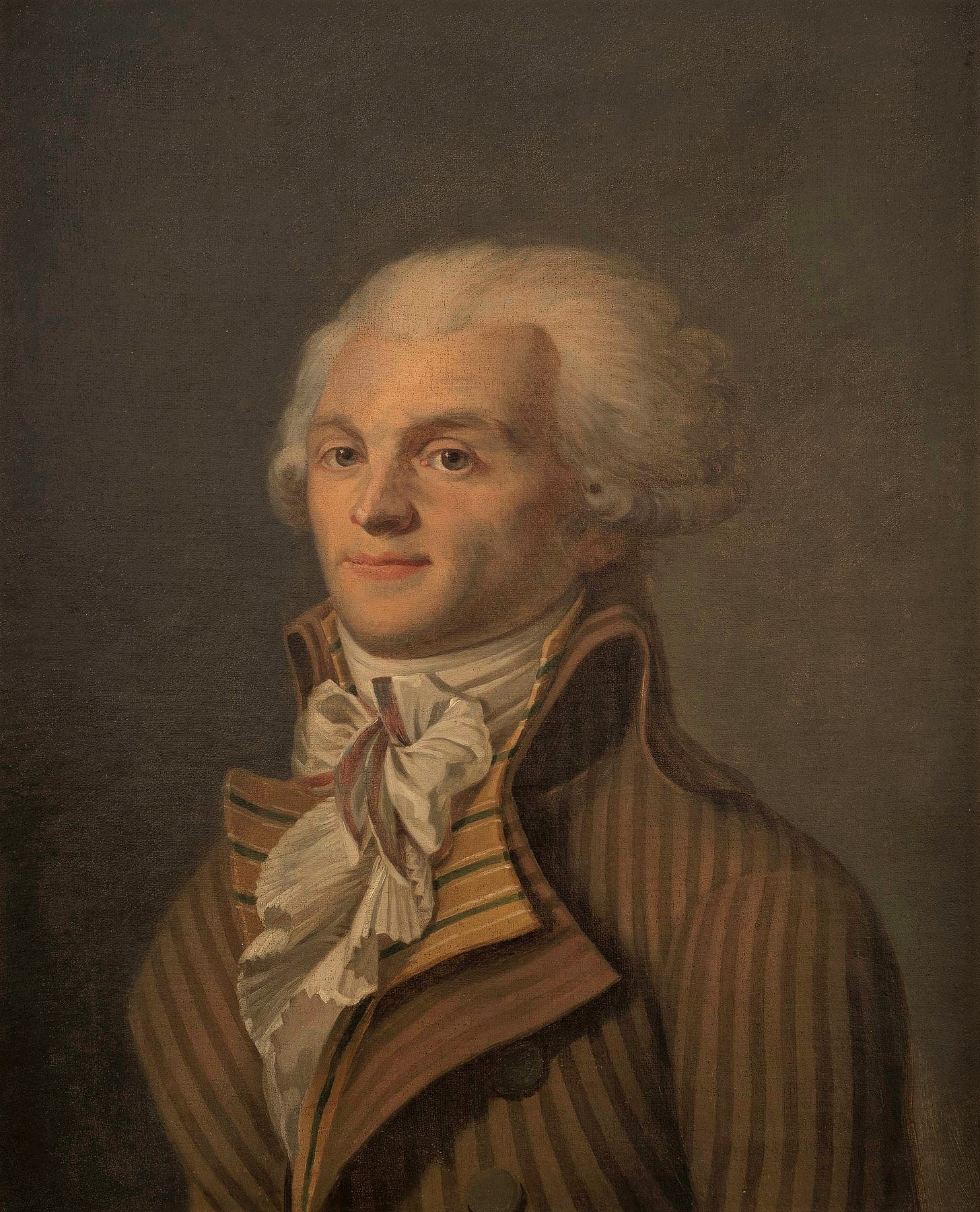

I came across the source text for this translation after becoming interested in Napoleon’s role and activities early in the French Revolution, specifically his relationship with Augustin Robespierre, brother of the infamous Maximillian. Early on in his career, Bonaparte was somewhat of a favorite of the younger Robespierre, who protected him after his final flight from Corsica and worked with him during his time in southern France. What then, in that case, was Napoleon’s relationship with the elder Robespierre?

Despite his revulsion at the popular excesses of the Revolution, see the Tuileries Palace, in his early career Napoleon was a confirmed revolutionary. This can be seen directly in his fight for Corsican freedom couched in republican terms, in his delight at the removal of those barriers that his relative lack of nobility put up to his promotion, and finally in the Souper de Beaucaire, an essay he wrote campaigning in the vicinity of Avignon. In it, with seeming sincerity, he denounces variously the aristocrats, the false republicans and those who would crush the true friends of freedom. You may also deduce it indirectly in that he shared many of the cultural references of the more infamous revolutionaries, though it might be recalled that these authors were the bedrock of the time’s cultural milieu. From his love of Rousseau, “Oh why did you have to live only 60 years, in the interest of the Truth, you should have been immortal,” to that of Voltaire, along with his idolization of Rome and Sparta derived from Plutarch, but for his provincial Corsican upbringing and military education, he had the makings of a Jacobin.

His revolutionary sympathies, and more particularly those for Robespierre, can also be found in the following text, a contribution to Annales Révolutionnaires by E. Gallo, that takes the form of a heated post-dinner debate. Gallo’s source is an obscure poet by the name of Jean-Pierre Collot, who, in the notes to his unfinished poem, La Chute de Napoleon, began the year of the return of Napoleon’s ashes to France, offers some autobiographical details and more interestingly an account of a conversation at Ancona in 1797 to which he was party involving the then General Bonaparte. To give credence to this tale, Gallo writes that Collot was a soldier in the Army of Italy, assigned to the supply department where he rubbed shoulders with the Comptrollers General of the aforementioned army, Chauvet and Lambert. In this capacity he would have reasonably had the opportunity, if not to converse with the general, at least to be present when he was holding forth, as he did in this instance.

Even if this account is not entirely correct, it does however shed light on how Napoleon was perceived after his fall. The poem was written in the 1840s, a date by which Bonapartism had coalesced as a political stream, and though not to the extent of the monarchist factions, it was nevertheless a ‘conservative’ element in French politics. This was one way of seeing Napoleon’s legacy. Another one, whilst not progressive in the modern sense, sees Napoleon in continuity instead of in rupture with the Revolution, a current that figures such as Chateaubriand would perhaps have appreciated, comparing Napoleon as he did to Nero, “vainly does Nero prosper.” A current embodied by figures such as General Lamarque of Les Misérables fame. Lamarque was an ardent critic of the restored monarchical regimes and used his position as one of Napoleon’s generals as a source of legitimacy. Louis-Napoleon even once joked of being a socialist…

Regardless of whether you see this obscure note on an obscure poet’s obscure poem as entirely apocryphal, or conversely a faithful account of Napoleon’s true sentiments towards the one who, as Jacques Olivier Boudon writes in his book Napoleon: Le Dernier Romain, was the last man before him to really embody the state, it is at any rate an interesting exposé, using Robespierre as a model, of the Napoleonic conception of the raison d’état and personal power. Napoleon found these ‘qualities’ lacking in the early years of the Revolution, as men from Louis XVI to Brissot, through Barnave and La Fayette, failed to grasp the situation for what it was and impose themselves.

Throughout the account, Napoleon expresses unbridled enthusiasm for Robespierre’s ruthlessness and cunning for the salvation of the patrie. And whilst Napoleon was appalled at the lawlessness of warfare at sea, complained of the treatment of French prisoners held in Great Britain, and applied a humanistic model to the treatment of his own men, he really was no stranger to extremity in service to raison d’état. Napoleon is said to have decried la guerre à l’eau de rose (war through rose tinted glasses or war fought sentimentally), that tendency for modern armies to hold back from the total destruction of the enemy. He praised the Romans “at the battle of Canae,” who, “redoubled their efforts, for fear of being raped, murdered or pillaged, whereas modern wars are fought à l’eau de rose.” He also ferociously combatted that tendency of officers to surrender in battle, especially in open field, even when heavily outnumbered. “We must in that case, proceed with decimation, like the Romans,” he wrote. See also his willingness to submit all Europe to his Continental System, a measure unheard of in scope for the time, and to embark upon the monumental 1812 campaign to bring Russia back into the fold, all to secure France’s territorial gains and the security of his new state. In this episode he appears almost as the incarnation of raison d’état. This attitude, along with the emphasis on the virtue of antiquity, demonstrates Napoleon’s break with the statecraft and war-fighting philosophy of the proceeding age. With his references to Agustus, this side of Napoleon is amply represented in Collot’s account, apocryphal or not.

Napoleon sought to create a state that was administratively revolutionary: a uniform law code, subordination of the church, merit-based promotion, and social reform, without the ideological radicality, represented by a slow return to personal then dynastic power. There is some evidence in this account that he recognised this aim in Robespierre’s policy, though in an exaggerated and polemical manner to my eyes. See his prediction of a restoration of public religion whose first steps was the Cult of the Supreme Being, organised by the deistic rather than atheistic Robespierre, his affirmation of Robespierre’s disillusion with the excesses of the revolutionary Committee of General Security, a claim with some historical validity, and finally his praise for Robespierre’s lifting himself above factionalism to finally impose both himself and social peace.

Now to the account itself. Cited below is an extract of JP Collot’s poem, the one to which the account was appended as a note, and which was inspired by Napoleon’s attitude to statecraft, absorbed through the poet-soldier’s interactions with the general.

What the ignorant call crime of state,

Can be judged but by its result.

When by my long efforts, my tireless cares,

I have made our arms feared far and wide,

Forced peace upon our enemies,

And to my subjects given glory and wealth till they can receive no more,

Who will reproach me for my fleeting harshness,

That which the public interest judged necessary,

And of which I purged of all shameful excess.—JP Collot

“Since its origins,” he said to us, “France has had but one strong government, and it was Robespierre’s.”

The terrifying impression that this man’s memory had left in everyone’s mind was so fresh and deep that one struggles to imagine the surprise that this opinion aroused and how ferociously it was fought.

Far from abandoning it, General Bonaparte justified it with tenacity. “What is,” he said, “a strong government? It is one that has a well-defined aim, the unbending will to achieve it, the brute force to achieve the triumph of that will, and the intelligence necessary to channel this brute force. Let us look closely as to whether Robespierre held all of these. What was his aim? The triumph of the Revolution. He felt that a counter-revolution would be bloodier and would entail crueler and longer-lasting evils than those our revolution had already demanded and would demand yet. He thus wanted to see it through whatever the price. The utility of this aim does not seem to me to be open for debate.”

“His will to achieve this aim was as clear as day. The number of victims that he sacrificed, the number of families who wanted a reckoning for the blood of these victims, had convinced him that he would die a death of the cruelest and most ignominious sort if he failed. Hence, he could not take one backwards step.”

“Did he have the brute force required to achieve the triumph of his will? There has never been so formidable a display of force as his. He had but to give an order for it to be executed with neither delay nor obstacle from one end of France to the other.”

“He acquired it by declaring himself the implacable enemy of the royalty and the tireless defender of the people, those to whom he had opened up advancement, given work and whose unlimited purchase of state property he had facilitated. He further strengthened it by organizing on every square inch of France that Jacobin Club, imbued with his principles, animated by his spirit, and blindly submitted to his Code. It was with this instrument he had his blood-soaked decrees executed, and by having the Club participate in them he shackled it to his cause. Anyone who dared manifest opposition was obliterated, crushed, in that very instant. This man’s brute force was therefore without limit.”

“By it he triumphed over all the parties. Royalists, Cordeliers, or Girondins, all were either terrified into submission or annihilated. By it he was able to give France those powerful, well-manned, disciplined armies that spared us from the misfortune of seeing her invaded, pillaged and divided up for spoils. By it, in the hour of our most desperate need, he was able to obtain weapons, munitions and victuals and it was what kept the soldier who lacked shelter, uniform, pay or sometimes even food, from deserting. Could Robespierre have performed these miracles without that colossal power?”

“And yet could he command this force? No, and that is what doomed him. Not being a man trained in the military arts, he had to entrust his arms to a soldier. He dared not choose from amongst our best generals, feeling that he could turn him into a blind instrument, or perhaps fearing to give himself a rival. So, he put that pathetic Hanriot at the head of the garrison of Paris, a non-entity with neither experience nor ability. When the time came, the worm lost his nerve and did not enter the fray. Yet, following 8th of Thermidor’s session, he should have seen as clear as day that if Robespierre and all his followers were not rescued that very day from the assembly members, who from the speaker’s dais had dared attack and accuse him, they were doomed. Payan, a more farsighted man that Hanriot, pushed him to have them arrested and sent that very night to the guillotine. The forces he had to hand were more than sufficient to carry out this coup de main, and if he had followed through, the next day Robespierre would have been more powerful than ever.”

Murmurs followed these words. “What! You think that monster could have kept himself in power? And yet he had been marked for death for two months. His power waned daily. His accomplices, terrified by the excesses they had committed, no longer wished to follow him, several had distanced themselves. Besides, all those representatives that he could not have or would not have dared slaughter on that day, threatened with the same fate as their colleagues whose death they had just witnessed, would not have rested until having rid themselves of their executioner.”

“Doubtless,” he replied, “had he persisted, had he not reassured them. But finally secure in victory, he would have as early as the next day halted the executions, forbade all arrests, and created a clemency committee charged with, starting with the least dangerous, steadily freeing prisoners. He had been preparing the groundwork for such a measure for some time. He no longer made an appearance at sessions of the Committee of General Security, sharply criticized its excesses, and marked out the perpetrators.”

“And could France have put much stock in his voluntary return to human feeling? No, we would have all attributed it to fear. Do you think that rescued from the Terror we all could have continued to tolerate that monster? No, not at all. The torrents of blood shed on the scaffold cried out for vengeance and would have gotten satisfaction. Besides, his accomplices themselves, alarmed by this backwards step, would have murdered him before he could have despoiled them of their power.”

“He would not have done that, he needed them far too much. He would have simply focused on squashing the factions, playing them off against one another. He would have said, “look Jacobins, if you cause my downfall, you are all doomed. I am doomed if I cause yours. My only strength is your strength. Your only strength is mine. Let us therefore endeavor to sure up our power. Yet to achieve this end we must change course. Enough blood has been shed, perhaps even too much. France cannot tolerate the sight of it for much longer. Let us stop with the bloodshed. We will put all that nasty business on the heads of the traitors that we have put to death. They pushed the Revolution to excess, to make it fail,” we will say. “If we want to reap the Revolution’s rewards, we must bring it back within sensible limits. The only one I desire it to be able to repay you for your noble efforts.””

“To the Royalists, he would have said, ‘Beware of provoking even the smallest disorder, of creating the fear of even a hint of counter-revolution. You will worry the terrorists. They will demand a crackdown, quick and bloody both. I would no longer be in a position to put up any opposition. They would murder me if I tried. You would then see the Terror reborn. I alone can keep a lid on things. But only as long as you stay calm and no longer think of the past. You must forget it, under threat of seeing your blood flow once more. I have reduced your suffering. I want to reduce it further, remove it all together if possible. But do not be difficult, be happy with the guarantees I have already given you. I will not be long in giving new and better ones. Let my position consolidate if you want me to be able to heal your wounds.’ This tone and carefully given favors would have kept the peace.”

“This arrangement would not have fooled anyone. The wounds were too fresh, too deep, for the injured parties to content themselves with such a remedy. But even supposing that they were happy, the worm would have been soon finished off by the state of the finances. Every day, whether by the unbridled printing demanded by government expenditure or more likely by the introduction of forged notes within our borders by foreign powers, the assignats (paper money) were losing value. The creditworthiness of the state was tending to zero, and the requisitions, without the backing of the Terror, would have dried up. Our armies would have disbanded for lack of food, foreign powers invaded hand in hand with the Royalists, and Robespierre, thrown to the dogs.

“Stop fooling yourselves. He would be able to produce his own resources. He would only to have pushed the armies onto foreign soil and have them live off it in abundance, much as they do today. As for the death spiral of the assignats, much like what was accomplished afterwards, he would have taken them out of circulation, justifying this measure by the necessity of putting an end to the invasion of fakes, and pronounced at the same time that those confirmed as legal tender would continue to be accepted in payment for biens nationaux (confiscated state and church property sold to the public). He would then have demanded that taxes be paid in specie, raising them as required to fulfill his needs, and easily produced all the resources necessary for the functioning of his government. In deft hands, France is too rich a country to die from the state of its finances. The party chiefs, smothered with favors, would have preached these measures, the papers and the best writers, handsomely paid-off, would have exalted his genius and the goodness of his government. Whilst those who would dare attack it either intimidated or struck down, but either way reduced to silence.”

“To increase the number of his followers he would have rebuilt the altars, reestablished religion and protected the clergy, the Festival of the Supreme Being was the first marker along this route. He was far too clever to ignore that the law was insufficient to hold the people in obedience, that you must bind them with religion. He would have gone about it with that unrelenting skill that he applied to all his designs. The priests, charmed by this unhoped-for return to grace, would have supported him, and once he had succeeded in returning to them their standing and consolidated their position, they would have preached that the heavens had deigned to enlighten his mind and flood him with grace. Perhaps they would have ended up making him a saint.”

“Look at Augustus. He had bathed in the blood of his friends, kin and mentor. But when he had rid himself of [Mark-]Anthony, had brought all the factions low, put an end to the bloodshed, brought his triumphant arms to every corner of the empire, and returned abundance and the games to Rome, the foremost authors of his time sang of his clemency, his genius, and the brilliance and goodness of his government. The foremost patrician families accepted his laws, and the Senate proclaimed him emperor and father of his country. And, after reigning in glory and peace for forty years, he died in peace and was missed, after which the Romans made him a God. How true it is that what we call law is in fact force.”