Summary of the Draghi Report

The EU roadmap for the next 20 years

Over the last month, 26 European lawmakers, power-brokers and senior civil servants faced their nomination hearings for their new positions as EU Commissioners. While covering these long procedures, bored news reporters came up with a rather amusing game: every time a nominee mentioned the word “competitive,” you had to take a shot.

While I can imagine these journalists were trying to have some fun, many of the people in the Brussels-EU complex did understand that there had been an important vibe shift, especially felt during those hearings. Green policies, “equality,” “democracy” were of minor importance when compared to the bigger issue: EU lagging behind the US in innovation and decreased competition with the rest of the world’s major economies.

EU companies spent around EUR 270 billion less on R&D than their US counterparts in 2021, largely because we have a static industrial structure dominated by the same companies and technologies as decades ago.

The top 3 investors in R&D in Europe have been dominated by automotive companies for the last twenty years. It was the same thing in the US in the early 2000s, with autos and pharma leading, but now the top 3 are all tech companies.

The core problem in Europe is that new companies with new technologies are not rising in our economy. In fact, there is no EU company with a market capitalisation over EUR 100 billion that has been set up from scratch in the last fifty years. All six US companies with valuations above EUR 1 trillion have been created in that period of time.

This lack of dynamism does not reflect lack ideas or lack of ambition. Europe is full of talented researchers and entrepreneurs. It is because innovation often lacks synergies, and because we are failing to translate ideas into commercial success. Innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by the lack of a Single Market and an integrated capital market, stopping the cycle of innovation in its tracks.

As a result, many European entrepreneurs prefer to seek financing from US venture capitalists and scale up in the US market. Between 2008 and 2021, close to 30% of the “unicorns” founded in Europe – that is to say, start-ups that went on the be valued at over USD 1 billion – relocated their headquarters abroad.

—Mario Draghi on the presentation of the report on the Future of European competitiveness, September 17th, 2024

At least on a surface level, the American business model, which has produced the largest amount of wealth in history, seems to be more oriented towards innovation, whilst the business model of an EU country is more oriented towards keeping a certain status quo (“like a museum”). Although it would be interesting to analyze the reasoning behind this observation, and whether it holds up against thorough scrutiny, today I will focus on the Draghi report, the most explicit and lengthy roadmap ever produced by the EU and the most open attempt to reverse the competitiveness problem.

This document published on September 2024 was overseen by Mario Draghi, a.k.a. Super Mario. The ex-PM of Italy, ex-Goldman Sachs managing director, MIT alumni, is one of the brightest minds on economics today. A decade ago, a single well-delivered line from him on a forum would give assurances to the world financial system of the credit capacity of the ECB and the EU’s worst-performing economies.

“Within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough.”

—Mario Draghi speaking at the Global Investment Conference, July 26th, 2012

His credentials are, however, hindered by the fact that he is, indeed, a boomer (terminal case). His misconstrued worldview affects some of his views on innovation, economics and social organization, hence the viewpoints on certain parts of the document (like the sections on AI) becoming indistinguishable from a consulting agency report. Despite this, Draghi and his team not only correctly identified most of the issues weighing down the EU economy (red tape, fragmentation, financial system, infrastructure, and energy grid), but also bigger more unstoppable factors like the severe upcoming population decline, labour shortages, dependency on rare raw materials.

Though the usual sensibility towards environmentalism is present throughout this document, anything related to DEI is quite simply absent (gender equality is barely mentioned in passing, with a single graph on ‘Gender gap across fields of study’ on page 263). The few mentions of European values, like “democracy” (lmao) and appeals for citizen engagement read like intentionally cynical lip-service rather than actual statements of belief. Vague geopolitical predictions on the direction of the continent (like Jean-Claude Juncker’s 2017 white paper on the future of Europe) are left out. Policy proposals, numerical analysis, elaborations on previous policy papers and case studies take center stage. For all this, Draghi’s report deserves a deep-dive.

The longer Document B (In-depth analysis and recommendations) contains two sections detailing various types of policy proposals (sectorial and horizontal policies). Here we will divide it into two main areas: economic reforms towards innovation, and internal dynamics of the private sector.

Reforms on the internal dynamics of the private sector

The EU member states present enormous asymmetries between each other despite forming a compact economic bloc. Poland has effectively had full-employment for the last half-decade, unparalleled growth for the last three decades, relatively good governance for its citizens, and a solid welfare state. However, it has no major national industries, no tail-end industry, no national car brand and the ranking of the biggest employers in the country is mostly comprised of subsidiaries of foreign multi-nationals. Though there are nuances, these characteristics are more or less common in the ex-Warsaw Pact countries that joined the EU. In contrast, Germany has a century-old industrial base that survived two world wars and various occupations, yet it remains quite erratic on basic government policies such as public transport, energy, and education.

Each country has since the beginning of the continental union 70 years ago, worked on unifying certain policies for convenience, but also on reducing costs on redundant areas. Barring those policies that affect the members states planning (monetary policy, agricultural handouts, information processing for bureaucratic ends and international treaties), each country manages its own affairs with room for manoeuvre. In this document, integration takes center stage on a few key areas which had remained relatively untouched during the last decades.

Energy

One of the major issues regarding volatility and exorbitant energy prices, both in industry and for households, has been the reliance on a small number of energy sources. Though the energy spikes during the first year of the Ukraine war haven’t been as bad and prolonged as other non-EU countries (like, for instance, the UK) they showed the vulnerability of relying on Russian LNG for much of the energy mix of various EU countries. However, it also highlighted the redundancy of separate energy contracts for all the EU states with near identical consumption. Both single procurement by multiple state parties, as well as data gathering and co-ordination, aim to secure favorable deals on market-sourced contracts.

A continent-wide grid unification, as an end-goal, remains out of the table for now. Instead, harmonization on an administrative level and a diversified energy mix is proposed so as to favor cross-border energy production. Countries are delivering energy surplus (whether planned or not) in peaks of energy production, such as in the North Sea wind farms, on a recurring basis. Because of differences in power transmission infrastructure and simple lack of communication between governments, such connections between neighboring countries have often been unfeasible until now. Hydrogen storage and production is alluded to as an important energy source “in decarbonizing hard-to-abate sectors”, though its widespread use remains far on the timeline and its adoption is still a hard call to make by these industries (i.e. chemicals).

Energy-intensive industries and Clean technologies

Though the report proposes considerable cuts on red-tape in order to favor lower energy prices for industrial businesses, a main concern in this part of the private sector is the rollout of the CBAM (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism). This form of tariffs on imported goods is aimed to push foreign manufacturers to reduce their ‘carbon footprint’, establishing a more leveled operating framework for those industries aimed at reducing their carbon emission targets.

Scenarios in which circumvention takes place by non-EU actors is expected to continue (such as deliberate scrap-generation for highly recyclable materials). Because of this, externalities on the green energy agenda, considering the weight given to ‘competitiveness’ into the future, are to be closely followed and reconfigured during the next few years. Manufacturers of finished goods compliant with low-emission regulation may find better buyers in the domestic EU market than elsewhere, incentivizing integration of supplies; that is, if they find actual buyers at market price.

“Subsidizing green energy production... cement, chemical, steel, this goes everywhere in the economy.”

—The future of European competitiveness: a conversation with Mario Draghi at the Bruegel think-tank, September 30th, 2024

The establishment of green regional industrial clusters around the energy-intensive industries is especially significant. The report proposes incentives for businesses which unify their whole recycling process, considered as integrated manufacturing units.

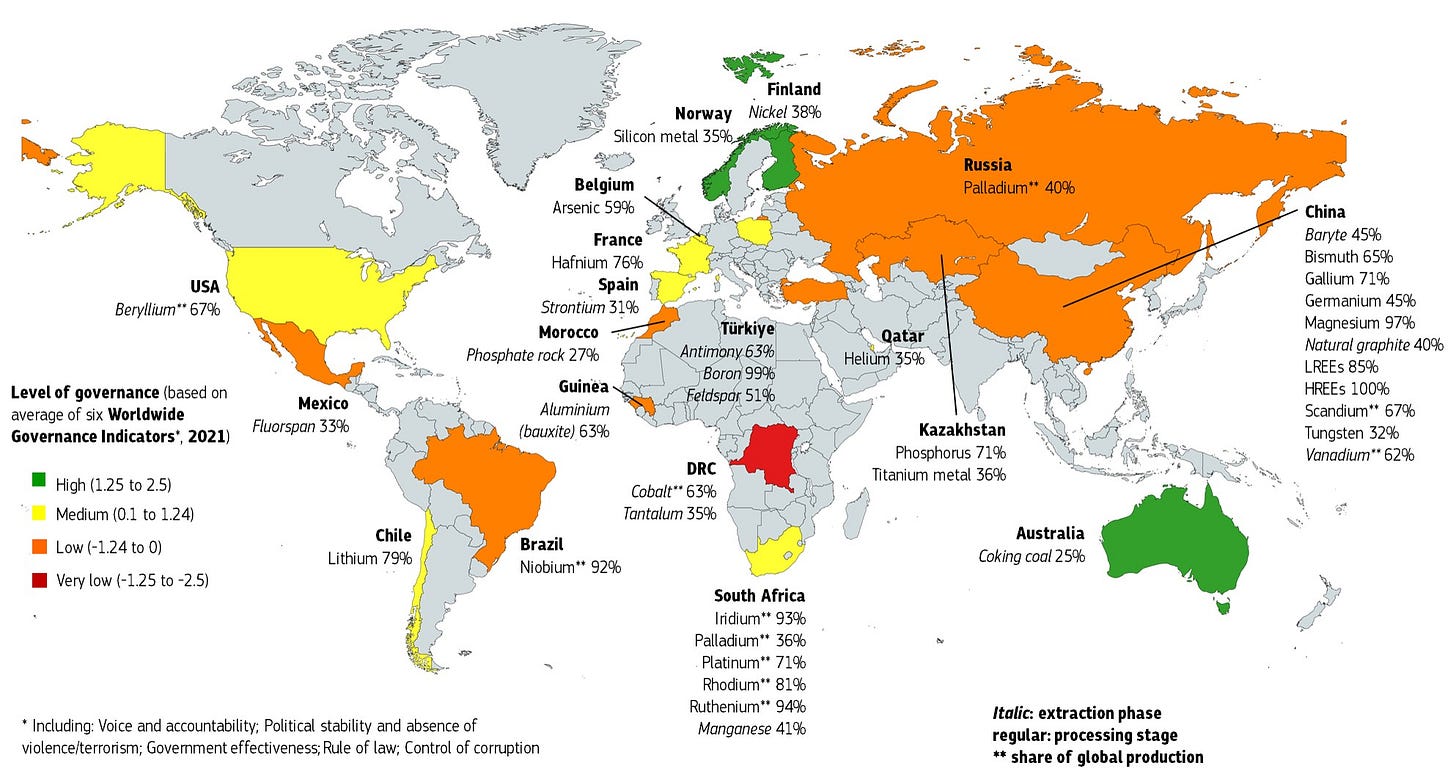

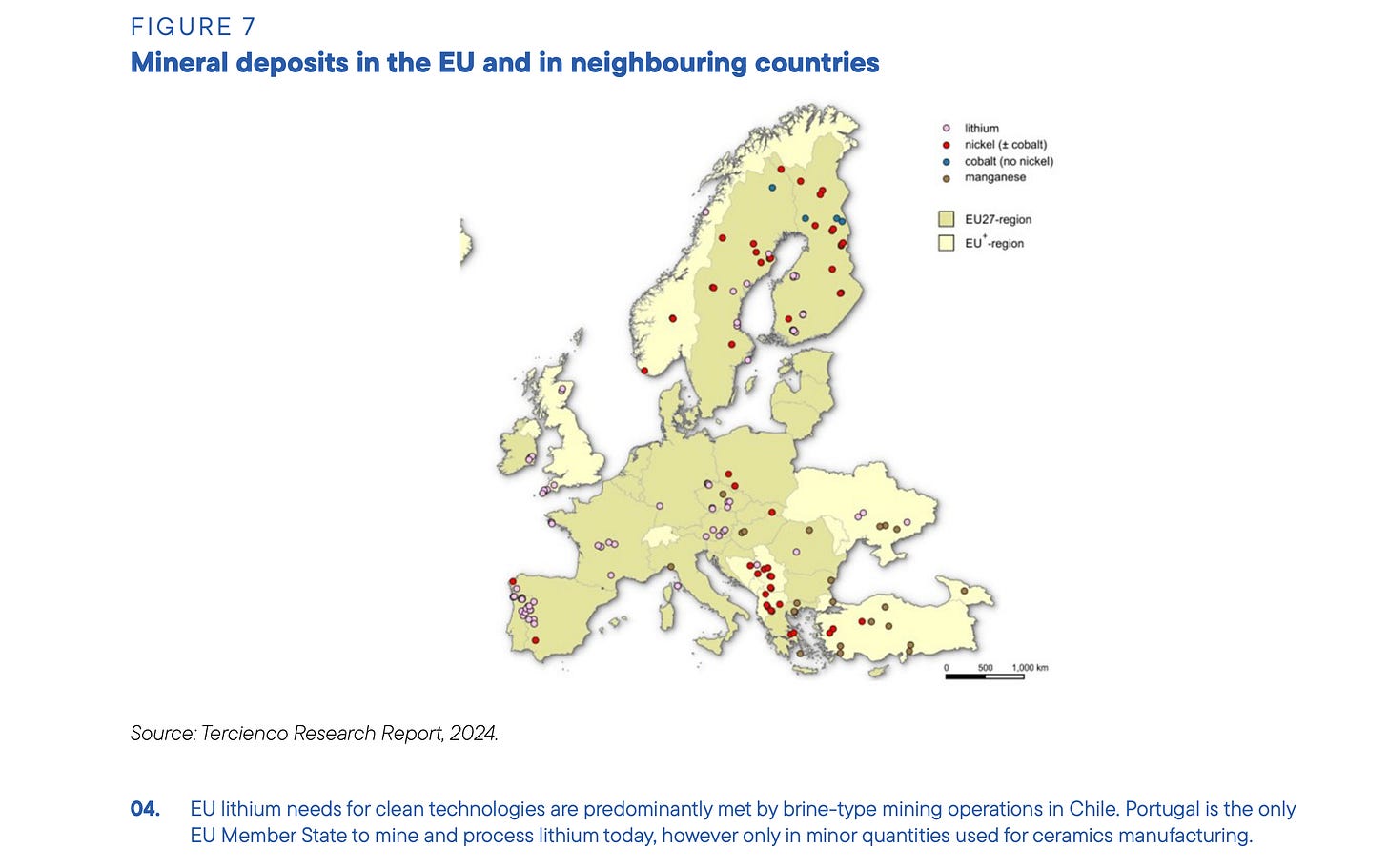

Critical Raw Materials (CRMs)

Self-reliance will grow in importance in a world where free trade becomes less so, but Mr. Draghi makes no quibbles when talking about the current reserves of raw materials on EU soil.

We are different from the United States. We cannot build a protectionist wall, we cannot do it and we wouldn’t be able to do it, even if we wanted to do it, because we would harm ourselves. [...]

The WTO rules were the child of a world where there was geopolitical harmony, were there was basically overall agreement, and where free trade was basically agreed by everybody. Although, this is a very interesting thing, the first violation of the WTO rules [was spotted] in a report by the then president of the WTO in 2003, by the Chinese government! And it was a big violation. Nobody did anything, nobody said anything. Why was that? Well, because it was good business at the time! It was a good thing to ignore this. And the geopolitical configuration would allow to do that. So things have changed.

—M. Draghi, Bruegel

The EU is limited on its natural resources and has to export a significant amount of raw materials to feed its industries. For the last decade, the European Commission keeps an updated list of CRMs evaluating its importance, as well as giving important information on its supply and economic importance. The mention of CRMs in this document serves as a reminder of future instability rather than a major policy drive. New mining operations may open, more specifically, for the materials needed for EV batteries.

It is a given that there may be shortages of certain materials, either because of tariffs or conflicts. To reduce risks and avoid price peaks on the LMEX due to external factors (like those that took place during COVID and its aftermath), certain sectors are already considering the use of replacement materials (for instance, aluminium replacing copper for some types of power distribution lines).

Closing the skills gap

As population continues to shrink and youth unemployment rates in southern Europe remain at incredibly high levels, different proposals are discussed to restructure employment. Previous multi-billion euro programs, such as Erasmus+ (meant for cross-country employment offerings), have been rather ineffective over the last decade. In the report, a focus has been put on sector-specific initiatives and incentives for businesses to invest on academic and educational courses (despite SMEs showing less interest).

Still, the issue is rather complicated to address in a single way. Job programs tend to be captured by different organizations and used for self-serving means, like filling vacancies with immigrants for such courses as a pipeline to low-skilled jobs in the private sector (though the report doesn’t mention it). Something quite common and especially acute in countries like Germany.

The case study of Finland offers some interesting insight. Despite the worsening of the education system all around the continent (as the report suggests), Finnish institutions, both private and public, have developed special programs for workers to learn new skills at a variety of different levels and areas of the economy. The impressive figure of ‘2 of every 3 adults’ participating in formal or non-formal learning activities every year offers a model to replicate continent-wide from the country with one of the best standards of living and lowest unemployment rates.

Defense

Here we find a different proposals based on seemingly-neutral geopolitical assumptions. Because of each country’s preserved national sovereignty on these areas, complete coordination under a single policy framework is tricky and depends not only on how countries outside the EU operate, but also how the member states deal with each other.

On defense, EU countries have, at least at present, no ambitions of expanding their borders, but rather on guarding them against different types of external threats. Considerations on the use and deployment of weapons of war are, then, taken within an evolving environment. Leaving nuclear deterrence out of the equation, the actual warfare involved in EU defense looks less like Predator missiles against Taliban targets and more like tailored hardware for specific cases, such as the CAESAR, reviewed in a previous article.

CAmion Équipé d'un Système d'ARtillerie (CAESAR)

In the late 1990s, there were two artillery systems available for the use of the French Armée de Terre (Army of the Land aka Army):

Interest on increasing expenditure follows a desire for self-dependence in a world more prone to conflict. This, however, hasn't been well-received by US defense representatives.

It's all quite fascinating and encouraging in that the EU is readying itself to take on a greater share of the burden when it comes to defense and security. Does the U.S. have some concerns about the ways in which some of those initiatives are unfolding? Sure. [...]

When Europeans do state that they should purchase defense equipment or weapons only within Europe, we ask the question: Given the needs, given countries' determination to get the best capability and at the best price, wouldn't you want to allow countries to look to wherever they can find the assets that they need, in the timeline that they need it? And sometimes that takes you to countries that sit outside the European Union.

I appreciate what their medium and long-term view is, but I'm not sure that limiting purchases to the EU will really get assistance on the shortest timeline, to either our friends in Ukraine or to the countries across the alliance that have some real acute shortfalls.

—Remarks to POLITICO by Julianne Smith, former U.S. ambassador to NATO, October 22nd, 2024

Whether such comments are a well-measured criticism or a byproduct of a conflict of interest with the US “military industrial complex”, I’ll leave the reader to consider.

Transport

Regarding transport, similar deliberations must be taken. Setting aside the ever-expanding Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T) remarked on in the document, with the upcoming inauguration of new landmarks (ie, Brenner Base Tunnel, Rail Baltica, and the Turin–Lyon high-speed railway), there are circumstances by which hard limitations on the construction of new infrastructure have been put in place. These decisions fall to the purview of each member state, which may have vested interests (legitimate or not), to not have such highways built in the first place.

For example, much of the highway system in Spain nearing its border with Portugal remains unbuilt, without a clear reason given by the government in Madrid. Because of this, trucks dispatched from Bragança, Mirandela, or Porto (misrepresented on the map above) delivering goods to the rest of the continent have to take the slower national road or the long way north through Galicia, adding an extra hour to the trip. This situation hampers the transportation of Portuguese goods, worth billions of euros, every year.

On the other hand, we find the unfinished “Motorway of Freedom” that cuts through the middle of Poland. Over the last decade, plans to finalize the Eastern part of the A2 autostrada, connecting Warsaw with the Belarusian city of Brest, have been deliberately stopped by the Polish government. Trucks coming in and out of Western Polesia and the cities of Siedlce and Biała Podlaska have to use the National Road 2 instead, adding between 30-60 minutes on each trip. A similar situation takes place between the Polish city of Białystok and the Belarusian city of Grodno.

The reasons for not building these roads are simple: a highway connection with its Moscow-aligned, non-EU neighbor would facilitate a quick land invasion, with Warsaw sitting less than 200 kilometers away from the border.

Sustaining investment

Because of the custom, spread all around the continent, of saving rather than investing, as well as fragmented capital markets and preference for banks to fund new ventures, newer European companies remain relatively limited on size and growth. In order to facilitate the creation of a unified capital market, a proposal is made for turning the coordinating role of the ESMA to one of a sanctioning authority over EU financial decisions (a “European Security Exchange Commission”, à la US, as described in page 292).

Issues involving regulatory uniformity will be an inevitable headache for the legislators, as many of Europe’s stock markets give preference to different business and investors’ trends. Also, equity markets have a tendency to collateralize on real estate, which are based on centuries-old property law (specially on ius in re) and administrative customs. This remains one of the most nuanced areas of the legal code in each country and could cause major issues if large financial instruments were established on irregularly-priced asset-backed securities.

The case study of Sweden (which has had a bigger number of IPOs than France, Germany, Spain, and the Netherlands combined) is worth mentioning. Because of the deep involvement of pension funds on its investment environment, the country has had a moderate success story which may serve as a model once the wider EU capital markets unification has taken place.

A Common European Safe Asset is also proposed, though the nature of this security is only hinted at in the document. Its aim is to be incorporated on corporate and banking balance sheets as a sort of reserve currency of its own. It would most likely consist in low-risk, long-term loans with EU member states and the issuing EU institutions. By account of Draghi himself, “it’s not an essential ingredient” for these economic reforms.

These measures sum up to a push for scale, based on specialized industries and a circular economy as a founding stone for full financial integration.

If there is one common theme in the whole report is that we should strive to increase productivity growth [...]. The second message I want to leave is that the most important step that we have to undertake to achieve the objective is to integrate our markets; first, the single market.

Why is it so important? Because if productivity is the objective, scale, in many of the sectors we’ve analyzed, is the essential ingredient. And scale, you only get it if you integrate single markets, and then we’ll have money, and then, will have the need for financial integration. But the very first thing is to be able for the small innovative firms to scale up. We save a lot! We have plenty of money! What we don’t have is scale, which is hampered by cross-national barriers and cross-national regulation.

—M. Draghi, Bruegel

Economic reforms towards innovation

Though innovation is often associated with freedom from innovation, there are circumstances that facilitate it. The US economy, current manager of the world’s reserve currency, carries a big advantage (which could also be seen as a self-imposed responsibility) on this domain. At present, the EU plans to at least rival this position with an expanded financial sector set on the reforms mentioned above, as well as in a variety of specific policies on key areas.

Revamping competition & strengthening governance

A brief analysis of the EU institutions and their own competitiveness proposes a few specific reforms on coordination, simplification and cost-reduction, with the main goal being more effective decision-making (especially from the Directorate-General for Competition, as the reports points out). Because it is in the interest of each country to push the EU institutions to become as effective as possible whilst paying the least amount of money. Their issues are not of inefficiency exactly, but of wrong time and resource allocation, which is still contingent on each country’s national interests. Grants, for example, may not paid to all countries because they still have to ask for it; but date extensions will be delivered.

With these considerations, one can see how this part of the EU civil service remains relatively self-aware of its costs and inefficiencies and seems to understand how they can reduce them, despite the image they tend to give as over-spenders. Expenditure on NGOs and aid to foreign countries, which reaches the low billions, is linked to various political and financial interests, making it harder to remove from the EU’s budget (170 billion € in 2022, paling in comparison to the 2022 US federal budget of 6,1 trillion $; 6,4 trillion €).

Pharma, automotive, and space

These three sectors are, to varying degrees, some of the better-performing parts of the European economy compared to other economic blocs, despite an increase in competition from emerging economies.

Both the pharmaceutical and the aeronautical sector remain somewhat competitive on an international level. Cooperation between national health and space agencies of the EU countries for information sharing, testing, and coordinated action follows previous proposals on the EU agenda. Increase in R&D spending through various proposed EU institutions seems like a break in the trend in this relatively austere part of the EU budget.

The automotive sector, one of the major industries in the continent, faces the menace of a decreasing customer base, foreign competition and an increasingly growing second hand market, which offers better prices when compared to the new overly-gadgetted car models. Rather than proposing new policies for this area, the report advocates for the continuation of previous policies set up in the past (green transition, regulatory uniformity, increase in coordination on the supply chain).

Despite a deficient economic performance, it is relatively easy to find similarities on innovative capacity and on areas adjacent to these sectors. For instance, Airbus’ new A321XLR recently became the first single-aisle commercial aircraft to complete a transatlantic flight, whereas Boeing has grown a habit of inadequately assembling parts of the aircrafts on their production line, and whistleblowers dropping dead.

High-speed / capacity broadband networks

On the strangest part of this report we find a push for mergers in the telecom space. EU Internet speeds are among the highest in the world in many countries, and though there are wide variations between countries, broadband and mobile connectivity services are overall superior and cheaper than most of the world. The reasons given for this are rather peculiar:

In the telecom space we don’t want to have 27 national monopolies. What the report wants is to have a certain number of pan-European competitors that compete fiercely in national markets. These are the objectives, and to this extent I think these objectives are shared by, I think, everybody in this room and most people even in the European Commission, and perhaps not by national operators. But that’s what the report aims to have.

The second fact is that Europe suffers from a gap, an infrastructure gap, and especially an investment gap with US operators [...]. We have something like 35 main operators and 370 or so marginal operators. The US has 4, China has 5. So isn't this a cost for lower investment in Europe? The answer is yes. The investment CAPEX is way lower.

By the way, the whole thing starts from the fact that we need to fill this gap in infrastructure, in broadband, in 5G and so on. And the ones that invest in this infrastructure are telecoms.

—M. Draghi, Bruegel

Mr. Draghi wouldn’t say it out loud, but these infrastructures were either the effort of national public companies which laid out the original broadband, mobile and telephone installations on their own, or a private company which effectively held this monopoly. Such an infrastructure is expensive to maintain and is often rented to much smaller, regional operators which manage to easily turn a profit on more compact business models with considerable fewer indirect costs. Though this situation varies on each member state, it has been quite prominent in countries with larger telecom companies, such as Romania and Spain, in contrast with countries which never carried out a centralized infrastructure project, such as Germany, with much lower Internet speeds and reduced mobile coverage.

This legislative change is the final result of a long lobbying effort from various telecom companies to expand their business model towards their area of expertise, obtaining assurances that the deployment of newer, standardized networks will favor them over the smaller operators. If done right, it would allow for a faster, less congested broadband (very much needed for the upcoming AI effort) whilst keeping competitive prices for the EU customer.

Semiconductors

Here too, we see that geopolitical circumstances remain prescient. Almost all of the world’s states are completely dependent on computing technologies to process enormous amounts of information, data processing, and communication. Conventional thinking suggests that, despite an increasing possibility of new conflicts breaking out, the far-reaching world will continue spinning free of restrictions on trade in this indispensable area for all the countries, at least for some more decades.

European companies working on this domain (ie. ASML) are expected to carry a significant weight in importance. Nevertheless, the report advocates for their own initiatives, “focusing on supply chain segments where it has or can develop a competitive advantage”. Various projects will receive various EU grants aimed at procuring the manufacturing of fabs and chips on the continent. The development of new R&D initiatives for every part of the manufacturing process is unlikely, aiming instead on “back-end 3D advanced packaging, advanced materials, and finishing processes”.

Computing AI

The buzzword of the year has filled many pages throughout this document. Though it is early to tell, the full impact of this technology, Draghi and his team highlight its importance and the need for its use on various sectors of the economy (automotive, pharma). On the other hand, it is unlikely to be the real initiator behind these policies.

Because of the over-reliance on EU computer technologies over the last several decades, there’s an enormous gap, especially, on hardware and software development. Instead of elaborating on new AI legislation, the main focus on on these proposals lies on the expansion of data centers cloud services in EU countries, the latter currently provided exclusively by US and Chinese companies.

Competition between the US and the EU appears to not be too much of a concern, as one of the proposals calls for an increase in “cooperation between the EU and the US to ensure access to cloud and data markets.”

Accelerating innovation

Based on a more expansive finance sector, various policies proposals are discussed, most based on previous tendencies of EU institutions (simpler frameworks on R&I and regulating investment on R&D, investment on household names). An out-of-the-ordinary request for a ‘coordinated reduction of labour income taxation for low-to middle-income workers’ could mean good news for millions of workers in the lower earning brackets, especially the younger generations.

However, many of the policy proposals have a distinct flavor to it. If the aim is to revamp “innovation,” it is specially geared towards ICT, which is the area the US economy has aimed towards over the last several decades, facing its own set of downsides.

The dichotomy is that Silicon Valley deals in the world of bits, most of the economy is the world of atoms. The world of bits is computers, Internet, mobile Internet, software, that ensemble; and there’s been a narrow cone of progress around those kinds of industries. But then, you often have less good of an understanding for the sort of industries that involve in atoms, in building things. Real estate, which Trump is on, may be the stereotypical industry involving atoms. Those are the ones that are often much more heavily regulated than the world of bits.

And so, if you are in the world of atoms, you might be very concerned about government regulation. If you are in the world of bits, which is much less regulated, you might be much less concerned about government regulation. There is this big separation just in terms of what they do. I wouldn't blame that on just a blindspot Silicon Valley has. I think this is just a little bit too easy. Perhaps Silicon Valley has focused on the world of bits because it has actually become really hard to do things in the world of atoms.

When I was an undergraduate at Stanford there was a still a lot of different engineering fields you could study in the 1980s. They were all bad decisions. It was a bad idea to become an aero, astro-engineer, it was a bad idea to become a chemical engineer, a mechanical engineer. These were all industries that were all in structural decline because they were getting outlawed, they were getting regulated to death.

—Peter Thiel speaking at the The National Press Club, 31st October 2016

Conclusions

It is easy to foresee how most of these proposals will be implemented in a different fashion from its presentation on the document, with the final roll-out taking different forms (tax-breaks, EU grants, subsidies, increase, and reduction in different types of regulations). Uniformity and integration on key areas will be the most manageable proposals, whilst those involving softer policies, like education, may be achievable but not meet the desirable goals. Subsidies, often considered a dirty word, are a valid tool for reconfiguring certain key areas of the economy against countries which have already used them first for their own advantage (i.e. China’s EV market).

The point of these policies, again, is not to regulate new paths to competitiveness, but to clear these paths in a variety of ways for businesses and institutions. The EU countries have, in the words of Draghi himself, other advantages compared to other economic blocs:

For example, if these industries want to relocate to other parts of the European Union, that’s a process that should not be hampered. And we should do more however, because these industries are often rooted in their environments, they have long histories, they employ millions of people.

So that’s where, in a sense, we are in a better position than the United States. We have a strong welfare system that now it could be well put at profit through a re-scaling of the people in these regions. And it’s not in our values it’s not in our history, so there is no danger we actually abandon people like in fact happened in some parts of the United States in the 90s.

—M. Draghi, Bruegel

Even taking the present-day shinning beacons of American innovation as an example, Tesla and SpaceX, one can see that just a decade ago, they faced an extremely precarious situation due to unstable regulatory practices, arguably the biggest burden on innovative fields. In 2014, Elon Musk had to file a lawsuit against United Launch Alliance for monopolistic practices that favored Russia’s rocket manufacturing industry. Only 6 years later did NASA officially drop the Soyuz for the Falcon-9. In 2015, Germany’s Herbert Diess came close to standing in as Tesla’s CEO position amid significant turmoil from the company’s finances.

EU countries have managed to keep most of its industrial base on a competitive international level. The US, whilst pushing more aggressively for innovation, has sacrificed much of theirs. We will see to what extent the EU manages to catch up on these innovation areas whilst keeping the economic pillars which make it competitive in the first place.