Many of the intellectual, and political, classes of Europe grew up with the mythology of 1968. Whether they were active participants or not, is irrelevant. Many of them in fact made up their contributions. What is important, is that the event is viewed with some nostalgia, even romanticism, among a class of people who view the commotions of our era with some suspicion. They do not appreciate the contemporary magnitude of the damage created by their ideology, but they will nevertheless not let go of it.

It is too easy to believe that one fought for the emancipation of youth, of freedom, against supposedly oppressive forces at work at the time. In an era where many young people are incapable from forging their own destinies, it is comfortable to think that those student protests were the achievement of a lifetime.

It is high time to show with coldness, with lucidity, with disinterestedness, and without the passions which inhabit those people, the sequence of events. To do this, we will use the account of Alain Peyrefitte, who happened to be the Minister of National Education at the time.

May 1968, was in fact one of the first sparks of what we today call “the color revolution.” They began as a simple dispute on the grounds of a university in one of the more enjoyable suburbs of Paris (do note that Nanterre is where the riots of last year originated). The most prominent agitator, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, aka “Danny the Red”, was not even a French citizen. Because of the inaction, or rather weakness of the academics and authorities, things spread to a real crisis of regime. We will naturally also lay bare all of the foreign support for these movements at the time.

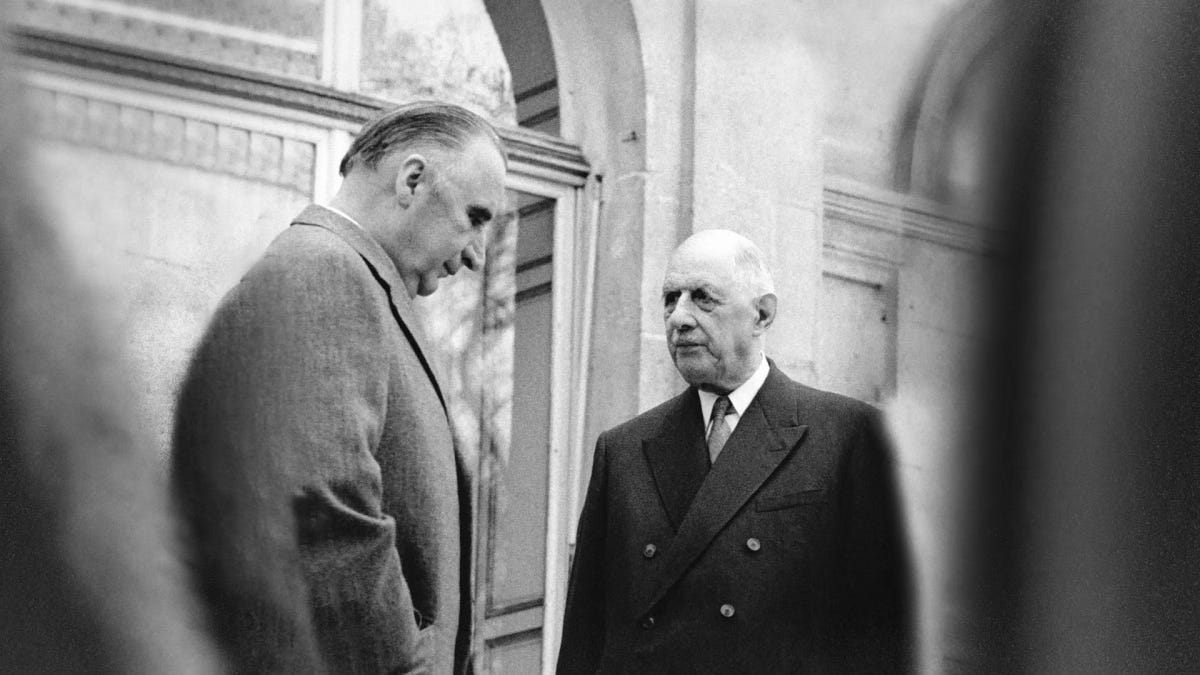

General de Gaulle had given the correct instructions at many points, but his government was either hesitant, or as we will see with Prime Minister Pompidou: actively working against him. The extent of the crisis resulted in de Gaulle’s sudden disappearance. It is often said today that De Gaulle “fled”. I will naturally show how ridiculous those assertions are, and instead let those who were there speak for themselves. General de Gaulle knew that he could not rely on his ministers any longer to ensure order. He had means, that would manifest on his return. But first, he needed assurances that the regime would survive the worst if needed.

What he actually did is leave Paris without informing anyone, took his family to ensure their safety, and sought refuge with his true allies: the Army. He reconciled with many of the Generals he had fallen out with over Algeria. They pledged their full loyalty to him and, armed with this base of support, De Gaulle returned triumphant to put down a brazen attempt to erase all of the work done to resurrect France since 1945, and 1958.

But this happens much later, today we will take a look at what preceded May, the actors involved, and how authorities reacted.

I hope you will enjoy this series, and I am convinced that many of our friends will see General de Gaulle in an even better light after reading it.

Lead-up to the events of May 1968, commotions in Nanterre ; appearance of Daniel Cohn-Bendit

Nanterre, October 1967.

In Nanterre, since the beginning of the school year of the Faculty of Letters, a group of students, in the name of “peace in Vietnam,” has been engaging in daily agitation, organizing meeting after meeting, and distributing leaflets. They use slogans that no one can refute to legitimize their disorder. What do they truly prefer: peace in Vietnam or the delights of disorder?

Quartier Latin, November 10, 1967.

Last night, a violent demonstration took place on Rue Soufflot. Three thousand very agitated students were shouting: “No to selection!” Not because of the projects we were still considering very secretly, but because of the influx of candidates preparing for the medical studies entrance exam.

I called Dannaud: “Are you not concerned about the violent clashes that occurred last night on Rue Soufflot with the police? Do you have any information on these extremist groups said to have organized and led this violence?”

Dannaud: ”Yes. The police prefecture has them under surveillance and creates daily reports. I can ask them to send these to you.”

From that day on, I receive this valuable information daily, just like the Élysée, Matignon, the Interior, and Justice departments. One cannot review this collection without admiring the accuracy of their information, the sharpness of their analyses, and the level of infiltration into the student environment they demonstrate.

Nanterre, November 17, 1967.

An assembly of sociology students in Nanterre decides on a strike. It is a minor technical issue that any reasonably autonomous university would have resolved within a few days. Before the Fouchet reform, one collected “license certificates”; since the reform, the system operates by years of study. Therefore, transitional provisions are needed to translate certificates into years. Naturally, some uncertainty remains. My position is that the faculties should resolve this residual issue themselves. But certain faculties, certain departments — such as philosophy and sociology at Nanterre — experience strong student pressure. The authorities turn to the ministry to find out how far they can go. The minister refers the faculty back to its responsibilities. The result of this back-and-forth between the faculty and the ministry is some chaos and a lot of irritation among the students, among whom there are always those who know how to seize an opportunity to challenge the class-based University and the repressive society.

The problem arises and is resolved in all faculties across France, but it is only in Nanterre, and in the sociology department, that it takes on a larger scale. On November 17, sociology students initiate a strike that extends to the following days. To the demand for generous equivalences is added the demand for student representation in faculty and departmental councils. The movement is more or less taken over by UNEF, which in Nanterre is controlled by the communists, as well as by students from the “Christian Community.” After about ten days of debates, expansion of the strike, classes disrupted by discussions, and a meeting between Grappin and 2,000 students in the large amphitheater, the dean authorizes, with my approval, the formation of “liaison committees.”

Nanterre, Monday, January 8, 1968.

The police prefecture's report notes that “about fifty students shouted some hostile remarks at Mr. Missoffe, Minister of Youth and Sports.”

It attributes the following comment to a certain Cohn-Bendit: “The construction of a sports center is a Hitlerian method intended to steer youth toward sports to distract them from real issues, whereas it is primarily necessary to ensure the sexual balance of students.”

It specifies: “The aforementioned has already made a name for himself at the Nanterre faculty for his active participation in all demonstrations held there. His personal views seem to direct him towards total anarchism, as he has notably worked to sabotage the elections for the board of directors of the ‘Federation of Study Groups of Nanterre.’”

An opportunity presents itself: it must be seized. I call Missoffe: “The guy who attacked you yesterday is German. A basic principle is that a foreigner staying in France must remain neutral. You can't let him insult the Republic through you. You need to initiate a procedure to expel him.”

Missoffe: “You must be joking! Expel a student because he said a few sharp words to me? I made everyone laugh by telling him that if he had sexual problems, he should just dive into the pool.”

AP: “But he responded by saying that your reply was typically Hitlerian.”

Missoffe: “It's a trifle. Forget it.”

I call Dannaud and explain that Missoffe wants to let it go, but that I don’t share his opinion. I insist that Cohn-Bendit should be expelled, even if Missoffe doesn't want to be in the spotlight, which I understand very well. After discussing it, Dannaud advises me to go through the Nanterre police station: “They will take the initiative to bring Cohn-Bendit before the police prefecture's expulsion commission. Let's treat it as a routine matter. We'll take care of it.”

Caen, January 18, 1968.

During a visit to the University of Caen, I enter the large amphitheater where all the faculty members are gathered.

As I reach the podium, accompanied by the rector and the deans, a slight noise from above makes me look up. I barely have time to wonder what is happening when an egg smashes onto the sleeve of my neighbor. Unfazed, we open the session. A friend later tells me, “Just a few centimeters off, and you would have become the minister with rotten eggs, much like Guy Mollet was the man with the tomatoes in Algiers!”

The imaginative leftist militant who managed to climb into the attic, sneak into the space of a false ceiling, crawl to our vertical position, and calculate his trajectory with enough skill, was neither caught nor even searched for.

An attack that has the semblance of a prank: a certain degree of violence has entered my landscape.

Nanterre, January 27, 1968.

The expulsion procedure for Cohn-Bendit is progressing, but not smoothly. Yesterday, at Nanterre, several dozen enraged students gathered to loudly demand its suspension. Dean Grappin requested the police commissioner of Nanterre to send a busload of police officers to put an end to these disturbances. The police officers, upon arrival, found themselves surrounded by a hostile crowd. They quickly retreated, amidst the jeers of a thousand students.

Grappin was deeply affected by this incident. In his view, the troublemakers were only a few at first, but the majority of students “joined them as soon as the police arrived.”

For having called the police, he was booed: “Grappin Nazi.” The former resistant was deeply hurt by this insult.

The presence of the police acts as a catalyst: it is the necessary and sufficient condition to create solidarity among students… Analysts at the police headquarters fear that “the competition between the various leftist groups within the faculty is not likely to calm things down but instead risks provoking a dangerous escalation.”

I call Fouchet first thing in the morning. He takes the incident philosophically. He has seen other such events during his four and a half years in the Ministry of National Education. “And I'll see more. Tell me about the violence related to the workers' demonstration that took place in Caen. That was a real fight, and those workers are real fighters. That genuinely concerns me. But Nanterre, that's just child's play.”

Paris, February 1968.

Bourricaud, a good connoisseur of foreign universities, tells me: “Do not complain about the agitation of our students. We are probably one of the countries in the world where they are the most peaceful. What has happened in the United States, Japan, Germany, Italy, has spread to Spain, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Look at the Eastern countries, Latin America. Everywhere, students are protesting. Often, they do so with incredible violence. Cohn-Bendit declares that they do not want to reform society; they want to destroy it. Consider yourself lucky that, here, they are content with words.”

The CAL — High School Action Committees — are starting to create disturbances in the high schools of the Paris region. They are showing a new level of aggressiveness. In the name of “peace in Vietnam,” they are loudly demanding the right to political expression within the school. There have been incidents at Buffon and Condorcet, from which a student was expelled.

Nanterre, Tuesday, February 13, 1968.

The main center of agitation in Nanterre is in the university residence. The militants of the FRUF, the association of residents, are at the forefront. They have decided that, starting tomorrow, the internal regulations will no longer be enforced and that student pickets will ensure “free movement” among the girls and boys on all floors: thus, the residence will be both liberated and occupied by the militants.

Council meeting of February 14, 1968.

I had a communication added to the agenda, without announcing it to my colleagues or reporting it through the spokesperson, regarding student unrest, particularly in university residences. I wish to keep it secret to avoid giving ammunition to those seeking a confrontation between the government and the students, between the regime and the youth.

AP: “The phenomenon is not specifically French, but international. For several months, especially in recent weeks, there has been a wave of often violent unrest —Germany, Japan, Venezuela, Prague, Madrid, Amsterdam, Quebec, Montreal, Rome, Louvain, Algiers. This unrest has spared neither the United States nor the Soviet Union in recent months, in protests against the sentencing of writers, nor China, with its university in Beijing, the 'vanguard' of the cultural revolution.”

“Some of these movements are, in a way, part of a tradition. In Madrid and Prague, it's a form of struggle for political freedom. In Louvain and Montreal, it's a linguistic, that is to say, national claim. Others have a new character. They, in liberal and prosperous societies, advocate violence as self-affirmation, as a mode of protest or action on events. Three themes are used to rally people: sexual freedom, euphemistically called ‘freedom of movement’ or ‘right of visit’; the desire to be masters in the university space (‘the Red Guards’ of Louvain — the supporters of ‘Rudi the Red’ in Hamburg); the Vietnam issue.”

“What is the situation in France? There have been incidents in Nanterre, Nantes, Clermont-Ferrand, in 1967, in the name of the struggle for the abolition of internal regulations. The FRUF is launching a week of unrest on the same theme, unrest that is to be manifested by the massive intrusion of boys into the girls' dormitories and girls into the boys' dormitories. It started yesterday in Nice, with tires being slashed and the director's house of the residence being besieged. It will continue in the coming days.”

“The theme of freedom of movement, the right of visit, is advanced primarily because it better rallies the hesitant than any other. But they also hold dear the unlimited right of assembly and expression, spaces allocated to student union or political organizations, and the total management of cultural animation funds.”

“The language is new: it is necessary, I quote, ‘to progressively paralyze the proper functioning of the University, because accepting this proper functioning is to accept the survival of a system that meets the current needs of the dominant class.’”

“In high schools too, a crystallization attempt is developing, with the creation of ‘High School Action Committees’ for a national action campaign on the theme ‘no to the barracks-like high school, freedom of expression.’”

“These activist minorities are essentially under the influence of the Revolutionary Communist Youth, the JCR, who are a branch of the Trotskyists, and the so-called Leninist communists who are actually pro-Chinese.”

“The Communist Party is still hesitating to follow or lead. For example, the communist mayor of Nanterre told Dean Grappin that the PC had nothing to do with the demonstrations of two weeks ago. But it seems obvious that if things were to escalate, the PC would avoid being outflanked on its left.”

“Facing this situation, and regarding freedom of movement, it is unhealthy to prolong a situation where facts and regulation agree so little. We once counted the girls leaving a boys' dormitory in the morning where they were not allowed to enter in the evening: 132! It is therefore better to get closer to reality. A new internal regulation would be based on a double distinction: boys and girls, adults and minors. In no case would boys be allowed to visit girls even if they are adults, visits from adult girls to adult boys would be the only ones authorized. Everyone should be home by midnight. As for minors, the parents would be called to take responsibility by requesting, if they wish, adult status for their son or daughter.”

“For the future, experience shows that the isolation of campuses is a factor of fermentation and unrest, failing to be able to make them Anglo-Saxon type campuses where professors live among their students. It is much better that university residences are integrated into an urban environment.”

“Finally, after discussing it with the Minister of the Interior, I sent precise instructions to the rectors yesterday on the conditions for potentially calling in the police forces.”

CDG: “Your residences, in any case, are anarchy. This agitation movement is due to the weakness of the leaders. Everyone gives in. No one has the courage to resist. And the regulations are not respected. You propose a solution, fine, but it just as well won’t be respected. If you take measures, wait until the end of the movement, otherwise nothing will be applied.”

Fouchet: “The unrest is not confined to the residences. We see organized and brutal movements emerging among the young, but they are elusive. This brutality is a new phenomenon. The Communist Party feels outflanked on its left. With it, we can agree on order. But with them?”

Pompidou: “There is some confusion and it needs to be distinguished. There are the specific problems of the young. The campuses gather young people outside the cities. If we build campuses, sexual freedom is inevitable. It is the freedom of mores, like in the Scandinavian countries. The Minister of Education must pursue a campus policy, or else we must mix students into city life.”

AP: “The campus policy, it’s done, unfortunately! Everything we've built in recent years are campuses. There are already 23…”

Pompidou: “There is a climate of protest, of violence; it is a fact of today's youth. And there is an extreme-left, Trotskyist movement. We find it abroad. There are means and organizations. They act in a concerted and simultaneous manner. Against this movement, we must not hesitate to act firmly.”

Nanterre, Wednesday, February 14, 1968.

According to the police, a coalition has formed between UNEF activists and FRUF activists with a common goal: “obtaining union and political freedoms.” A demonstration for this cause is planned for tomorrow, in “hall B,” at noon, the end of the midterm exams, ensuring a large audience: there could be a thousand students.

The prefecture, curiously, seems to place the responsibility for any potential disorders on the administration: “The slightest misstep could trigger violence and give weight to the extremists' incitements.” These incitements are indeed quite concerning: “The CLER students advocate a massive incursion of protesters into the dean's office.”

On the evening of the 14th, following instructions from the residence director, “the heads of the lodges let it happen: about a hundred militants broke down the doors of the two girls' dormitories and forced their way in. They stayed until 10:30 PM, but a minority remained all night to ensure ‘freedom of movement’...”

Nanterre, Thursday, February 15, 1968.

The demonstration took place, typically loud. But afterward, as announced, around sixty CLER militants broke down two doors leading to the administration tower. They went up to the 4th floor. “Mr. Grappin then came out of his office. They handed him a petition, which he refused to sign.”

Grappin's physical courage does not surprise me. The militants withdrew, announcing that he is now one of the targets of their guerrilla actions.

Irritated by his resistance, they went downstairs, gathered reinforcements at the campus restaurant — it was lunchtime — and ended up with 300 people in an amphitheater. The psychology professor who arrived to teach his class asked to speak and was met with jeers, insults, and hard-boiled eggs.

Paris, Saturday, February 17, 1968.

Dannaud announces the bad news to me: the expulsion commission ruled negatively yesterday on the request concerning Cohn-Bendit. His lawyer, Mr. Sarda, had invoked the young age and clumsiness of his client. He said his client “will heed the nuance of restraint he must observe.”

I fear this nuance will remain quite vivid…

Mr. Sarda didn't have to exert much effort. He could simply present the exchange of letters that took place between “Mr. Cohn-Bendit” and François Missoffe.

Here is the student's letter, written in a style as little “enraged” as possible:

“Mr. Minister,

You know that I am threatened with expulsion for various reasons, but it is clear that the request is mainly based on the remarks I made to you during your visit to the faculty of Nanterre. I believe there was a misunderstanding on that occasion, and I want to address this letter to you personally. I asked you why your report completely ignored sexual issues while addressing all the sociocultural aspects of youth problems. You responded that these were individual issues, like religious problems. I replied that every sociologist considers sexuality to be a social issue. You then answered that everyone could solve them and that the Nanterre swimming pool was precisely there to let off steam. I made the mistake of responding too briefly that this answer, which substitutes sport for sexuality, fit into the theories of the Hitler Youth. It is clear that I did not mean to call you a Hitlerite. The misunderstanding lies in the fact that this theoretical reflection could have been taken as a personal attack, or even as an insult to you. Believe me, Mr. Minister, that I regret it and would be distressed if you considered it as such."

The signatory did not regret or retract anything he had said. He only regretted that he had been misunderstood, due to his brevity. To which François Missoffe magnanimously replied on February 8:

“I had personally completely forgotten your intervention during my visit to Nanterre... The best thing would be for you to come and see me one day at the ministry. We could have a personal conversation, as I do, believe me, with many young people regardless of their opinions.”

Dannaud points out that the commission could hardly give an expulsion opinion for a young man who was clumsy and brief, whom a minister had invited to meet him, even if he hadn't taken up this kind invitation.

I remark that the commission's opinion does not bind its minister; he replies that the latter will surely not go against it.

Nanterre, Sunday, February 18, 1968.

As if to make me regret even more the non-expulsion of Cohn-Bendit, today's report from the PP subtly defines the actions of this character: “Since the beginning of the year and without ever exceeding more than fifteen members, the group of anarchist students has managed to be more or less directly at the origin of all the incidents that have occurred and to have sabotaged the union reactions following the events they themselves had created. (...) Their total critique, their complete disrespect for any authority, and their constant interventions have highlighted the contradictions of the various tendencies within the AFGEN.”

The report includes the “Grappignole,” the “war song of the Poles of Nanterre,” which mainly mocks those closest to the students: Grappin, but also Touraine and Lefebvre...

February 17-18, 1968.

Three hundred and fifty ultra-leftists of the JCR participated in the international days of “solidarity with the Vietnamese revolution” in Berlin on February 17 and 18. They have been learning from the SDS of “Rudi the Red.”

They will soon put into practice the lessons they learned; their anti-police aggressiveness has been noted by the prefecture, as well as their techniques, which are still new on the streets of Paris: monitoring police arrangements with messengers on mopeds, multiplying action through small commandos, “hopping” movements, etc. This will earn them some successes against an occasionally overwhelmed police force.

Matignon, February 21, 1968.

Multiple demonstrations are announced to conclude the “anti-imperialist days”: the pro-Chinese “Base Vietnam Committees” want to march on the Champs-Elysées; Fouchet denies them permission. However, he authorizes a demonstration by UNEF and JCR in the Latin Quarter, with the police prefect ensuring he can negotiate the terms with the organizers. The parade in the Latin Quarter is calm. But the Maoists defy the ban. Repelled from the Champs-Elysées, they head to the Vietnamese embassy, brush aside the few guards on duty like straw, and, in the blink of an eye, cover the facade with red graffiti, hoist the Viet Cong flag, before disappearing when the police finally arrive in force.

Pompidou tells me two days later, on February 23, 1968, after leaving a restricted Council at the Élysée: “Grimaud is quite impressive. He proves that it is better to negotiate with protesters to get their commitment to behave correctly, rather than banning demonstrations and ending up with underhanded tricks that no one had anticipated. This is what we need to do: de-escalate, bide our time, treat the protesters gently, instead of unleashing baby-like tantrums. This is the kind of police prefect I like.”

Nanterre, Saturday, February 24, 1968.

I need to see for myself what this much-talked-about Nanterre is like. But if I announce my visit, the authorities will want to await my arrival. This will surely lead to chaos, perhaps even brawls. The Missoffe incident is enough. So, this Saturday afternoon, I decide to go incognito.

Upon arrival, my driver, an African, agrees to leave the car and accompany me. We walk around for a long time between the restaurant, the university residences, the pool, the lecture halls, and the classrooms. There are few students. They do not recognize me.

The construction of the library is not yet finished. The construction of the socio-cultural center, which I had announced last May in the Assembly after Michel Debré's approval, has not yet started, as the financial controller stubbornly blocks the funds.

Is it this environment that drives students to revolt? Is it the feeling of being somewhat abandoned, left to their own devices? Is the environment of professors and assistants too distant? Or, conversely, is it too close? How can one not question the contrast between the calm of the law faculty on the same campus, where professors and students are moderate, and the chronic agitation of the humanities, especially sociology, where a few eminent professors of revolution teach?

What a paradox, that a faculty with so many masters who came around Grappin, with their enthusiasm and prestige, should drift away: Jean Bastié, François Bourricaud, Éric de Dampierre, Henri Lefebvre, Annie Kriegel, Robert Merle, René Rémond, Paul Ricoeur. All eager to innovate in this new university.

Amiens, Saturday, March 16, 1968.

The Amiens colloquium, like last year's Caen colloquium, stirs up many good ideas. However, the unions occupy more of the space. The new secretary-general of SNESup, Alain Geismar, gives a notable speech, ending it by hinting at the threat of a “solution in the streets.”

Paris, Sunday, March 17, 1968.

According to the prefecture's report, a general assembly of the Student Action Committees gathered around a hundred delegates.

Paris, Tuesday, March 19, 1968.

During the night of March 17 to 18, three American establishments (two banks and the TWA offices) were bombed.

Today, mobile groups, wearing helmets and armed with clubs, provoked the police forces in the Opéra district. One of them smashed windows at the American Express office. A few of these activists were picked up by the police; among them was only one student, Langlade, of whom I soon learn is enrolled at Nanterre.

Nanterre, Friday, March 22, 1968.

Langlade is a windfall for Cohn-Bendit. He is the missing link between the Nanterre agitation and the urban violence that has, since early February, put a somewhat surprised police force into conflict with determined but marginal revolutionaries, both in Paris and beyond the university campuses. Cohn-Bendit is gathering all the radicals from Nanterre to organize a “response” to the “police repression.” He proposes to occupy a symbolic location. After discussion, the chosen site will be the administration building, crowned on the eighth floor by the faculty council room. This is accomplished by 8 P.M. The revolutionaries joyfully settle around the table in this sacred space of the university.

I am quickly informed of this. After contacting Fouchet, it is decided that the police forces will intervene at 2 A.M.: the radicals have trapped themselves. However, warned in advance, they will slip away at 1:45 A.M., not without having named themselves the “March 22 Movement,” a reference to Fidel Castro's “26th of July Movement.”

The manifesto of the Movement, written during the night, declares in particular: “For us, the important thing is to be able to discuss these issues at the University and to develop our action there.” What issues? “The offensive of capitalism in need of modernization and rationalization.” The repression of the ruling class. The goal is the “critical university,” modeled after the Berlin example.

Paris, Saturday, March 23, 1968.

I call Fouchet: “The trap was foiled. But we can still catch the biggest fish. We won't have peace as long as this Cohn-Bendit remains in France. He exerts a real fascination over his peers. He must absolutely be expelled. I have been requesting this for more than two months. He instinctively finds the words and situations that win the crowd over. Young people find him amusing; he has pulled all sorts of outrageous stunts and there have never been any consequences. This time, we need to take action.”

Fouchet: “After spending four and a half years in the Ministry of Education, one knows that university privileges are a taboo. The university space is taboo. All university staff and students are taboo. What you accuse Cohn-Bendit of doing, he does within the framework of the university. Therefore, the university officials must take action. I know your deans and professors as if I had made them myself. They want the government and the police to take the authoritative measures they lack the courage to take. Later, they would blame us for the mishaps they have provoked. They need to be forced to take responsibility! I promise to expel him as soon as the university jurisdiction has pronounced his exclusion because, at that moment, he will cease to be protected by university privileges, but not before.”

I can only resign myself to accept the deal he proposes: expulsion from the country in exchange for exclusion from the university. The ball is in my court.

Direct expulsion would not have prevented protests. But it would have had the advantage of being a fait accompli. It would have deprived the protesters of their charismatic leader. The lengthy exclusion procedure, on the other hand, puts him in a heroic posture and allows him to lead the dance his way.

I did not appeal from Fouchet to Pompidou. Later, Pompidou would tell me that he regretted that. Later, I regretted not having done so. But how could one really imagine what was going to happen? Even the leaders of subversive groups did not foresee how successful they would become. Anyone who held authority rested on the soft pillow of... the absence of doubt. We had complete confidence in the solidity of the State that the General had rebuilt. How could a few students shake it when three-quarters of the army and most of the political class had failed to do so? That hypothesis was nonsensical.

Paris, Monday, March 25, 1968.

I call Rector Roche: “My colleague from the Ministry of the Interior is willing to expel Cohn-Bendit since he is a foreigner; but, out of respect for university privileges, he believes it is up to the university jurisdiction to speak first.”

The rector seems frightened by this prospect: “We must ensure that the university council will indeed decide to condemn him. It’s not a foregone conclusion. In any case, it’s a cumbersome procedure that we cannot initiate before the Easter holidays. Moreover, I am going on a study mission to the United States. But we could consider this procedure for the end of April.”

I call Grappin. I act as the advocate for the Ministry of the Interior’s reluctance to use its usual repressive means: “It is within the campus, with your colleagues, that you need to try to restore order.”

Grappin (overwhelmed): “But I have no means except for closing Nanterre! What do you want me to do about the emotions of these boys and girls? What do you want me to do about American policy in Vietnam? What do you want me to do with my forty janitors, half of whom are unreliable? What do you want me to do with my teachers, half of whom, and probably even more among the junior faculty and assistants, think the leftists are right and are determined that no harm should come to them?”

AP: “The only effective way to act is to strike at the head. The head is Cohn-Bendit and the dozen or so most excitable agitators surrounding him. The deal I made with my colleague from the Interior Ministry is in your hands. If you prepare a dozen files on these agitators, we have a good chance of obtaining their exclusion from the university, and Fouchet has committed to expelling Cohn-Bendit immediately in that case.”

Grappin (he pauses for a moment; I can sense that he feels crushed by the difficulty I am placing him in): “Since you are asking me, I will prepare a dozen files, but that does not guarantee that the university jurisdiction will agree to sanction them. And it also doesn’t guarantee that they won’t rally more comrades! This promises to be quite something.”

He seems to be in despair: “Last year, at the start of the academic year in 1966, when I saw that human tide advancing through the halls without even recognizing or seeing me, I thought: they are going to crush us. We were not made to accommodate fifteen thousand students in such precarious conditions. In Paris, the mass is tempered by absenteeism: they go to the bar, on the street, and to the cinema. Here, they are like hostages. The journeys are too long to return to Paris between classes. Since the start of the academic year, things have only worsened: now we control nothing. We have far surpassed the stage of dissent. We are at the stage of pre-revolution. The radicals have gathered and inflamed all the leftists. They have their stronghold, the residence halls. They have now become accustomed to interrupting classes in the lecture halls. The professors see no other solution but to close the faculty. In any case, we will have to suspend teaching for two or three days whenever the atmosphere becomes unbearable.”

AP: “Precisely, you have had to take on responsibilities this year that are not those of a dean. At the start of the academic year, there will be, side by side, the faculty of letters, the faculty of law, an Institute of Political Studies, and a University Institute of Technology. To manage this whole set-up, don’t you think we need a vice-rector, whose sole task would be to oversee the daily life and proper order of this whole structure, with each dean returning to their natural task, which is the management of teaching?”

Grappin: “What a relief that would be for me! I had thought of it myself; I would only ask for that.”

The incidents continue at Nanterre, now pitting marginal groups of all kinds against each other — communists, leftists, legalists of the FNEF, and the tough guys from Occident. The accumulation and unpredictability of the minor incidents of this guerrilla warfare are enough to disrupt the normal life of the faculty and the residence.

Salon doré, March 25, 1968.

The General questions me. I sense that he is not so much worried as intrigued.

CDG: “Why are these students agitating so much? What is driving them?”

AP: “They are Marxists who view the communists as mere pretenders to revolution. They see themselves as the true revolutionaries. They want to make the revolution now, not just talk about it. They want it immediately, not at some distant future.”

CDG: “Should we tolerate or ban their demonstrations?”

AP: “It depends. It seems to me that they should be banned on university grounds, which must remain neutral. But outside the university, at the Mutualité or even on the street, they can be tolerated, provided we can ensure with the organizers that their marches will not escalate. But this is not my responsibility; it's up to Fouchet and Grimaud. They are more inclined towards tolerance.”

CDG: “And what do you want to do practically?”

AP: “What can I do? The university authorities, the rector and the deans, are reluctant to take forceful measures — which they wouldn’t even have the means to implement — if they do not find a consensus within the university councils. However, the professors are divided, hawks and doves. The liberal university system relies on the idea that everyone, professor or student, respects the rules and plays the game. But, precisely, they respect nothing, they provoke authority. The University does not have the immune defenses to protect itself from those who want to destroy it.”

CDG: “So, what do you propose?”

AP: “It seems to me that the police and the judiciary should be able to handle the situation. They effectively got rid of the OAS; why not deal with the leftists? They have the means to overwhelm them with searches, surveillance, wiretaps, seizing their archives — in short, to hunt them down, paralyze them, scare them. It's not my area, but what is the purpose of the State Security Court if not to eliminate subversive movements? And these are subversive movements.”

CDG: “You think so? These kids? These jokers? Well, I'll talk to the Prime Minister about it.”

Nanterre, Thursday, March 28, 1968.

The exasperated professors support the dean’s decision to close Nanterre until next Monday, especially since a major “anti-imperialist day” is announced for the 29th.

Nanterre, Friday, March 29, 1968.

The leftists from Nanterre abandon their attempt to break into the closed university, but they move to Paris. Although Rector Roche has closed off access to the large auditorium at the Sorbonne, they gain entry using skeleton keys. They hold a meeting there and announce that the major event planned for the 29th is postponed to Tuesday, April 2nd — still at Nanterre.

Temporary closure of Nanterre, with the agitation shifting to the Sorbonne: a strange preview of the May 3rd sequence, albeit on a minor scale, which we adapt to.

Lunch at Matignon, Monday, April 1, 1968.

As promised, the General must have spoken to Pompidou: but the circle closes in on me.

Pompidou (irritated): “Listen, I was a student once. I marched, I protested, I even fought. But I have never seen such disorder. It can't go on like this! It is unacceptable that groups of rabble-rousers interrupt a class or occupy a university building overnight.”

I tell him what Fouchet and I have agreed upon. We are preparing the files on a dozen “troublemakers.” As soon as the Easter holidays end, the disciplinary committee and then the university council will be convened, and Fouchet has committed to expelling Cohn-Bendit as soon as he is excluded from the university.

On the other hand, Pompidou is much more lenient about what can happen in the dormitory rooms: “Let them mix together. In the meantime, they won't be thinking of causing trouble. And why should everyone go home at midnight? That’s exactly when it becomes the most enjoyable!”

AP: “In short, your approach with them is like Sganarelle’s attitude towards young women who cheat on their husbands.”

“It's not good to live as a strict censor;

You win over minds with a lot of gentleness...”Pompidou bursts out laughing and responds quickly:

“And defiant remedies, locks, and gates

Do not make virtue in women and girls”I laugh too, but I add, “Between unlimited gentleness and locks, the betrayed husband might be better off trying defiant remedies.”

I recount that a few weeks ago, on an evening when a meeting on this issue had run late, I arrived very late at Wladimir d'Ormesson's place, who had organized a dinner with François Mauriac. I apologize by saying, “I have serious troubles with some ginger. And besides, the boys in the dorms only think about one thing: screwing the girls. But how can you stop them?” François Mauriac then proclaims with his breathy voice, “The important thing is to be virtuous!” He repeats, “Nothing is as important for youth as being virtuous!”

Pompidou: “No doubt, but is it the role of the State to impose virtue?”

[…]

Nanterre, Monday, April 1, 1968.

Nanterre reopens. The reopening is almost symbolic, as the Easter holidays begin on Saturday. But symbols, everyone strives to shape them to their liking.

Students are welcomed by a message from the dean, broadcast through loudspeakers: “Freedom of expression is not contested, but it must be regulated.” A meeting room will be available for student organizations, which will manage its use through a commission where all of them will be represented.

Half an hour later, about a hundred leftists choose an auditorium to proclaim: “The spaces we need, we will take.”

Nanterre, Tuesday, April 2, 1968.

Two very different meetings have crystallized the Nanterre contradiction.

A meeting of the “enragés”. It starts in darkness. Anger rises. The police take note of Cohn-Bendit’s fiery remarks: “If the power is not restored in ten minutes, we will hold the meeting in the faculty council room... There will be no more informational meetings at the faculty, but political meetings... The dean asks that academic work and exam preparation proceed normally. This is precisely what we are saying no to... Accepting the culture provided by the bourgeois University is accepting to participate in capitalist exploitation. Is science neutral because it is proclaimed as neutral? It has been involved in all the massacres of our time, whether under Hitler, Stalin, or Johnson. Neutrality serves the bourgeoisie since it endorses adherence to the existing social system. We must denounce the cynical and repressive nature of bourgeois science.”

The newspaper Combat, under the signature of C. C., had previously described Cohn-Bendit as a “madman” and a “walking pile of dung.” Now, the same author is charmed: “From this adolescent, Germanic Danton-like face came a surprisingly soft voice that contrasted with the violence of his remarks.”

Cohn-Bendit then hands the floor to Carl-Dietrich Wolf, president of the SDS, the revolutionary movement of West German students; he translates the speech as he goes: “Do here,” concludes the German revolutionary, “what we did in Berlin, the Kritische Universität.” His speech is punctuated by applause, chants, and slogans that resemble cha-cha-cha tunes: “Che Guevara Che-Che” or “Ho! Ho! Ho! Ho Chi Minh!”

In the second auditorium, another meeting brings together around a thousand students, but moderate ones, who come to proclaim their desire to work peacefully and force the “enragés” to submit. Didier Gallot, president of the Law Faculty’s student body of the FNEF, declares: “We need to show that there are not just bearded and long-haired students who want to avoid end-of-year exams. The rise in agitation over the past fifteen days is not accidental; it is the same across Europe. The presence of a German student this morning at the ‘enragés’ meeting was entirely unacceptable. The ‘enragés’ demand freedom of expression. Their freedom of expression is dictatorship. You demonstrate that the majority of students are not behind 300 agitators.” He calls for the agitators to be expelled.

The history department, for its part, adopts a resolute resolution: “It informs the higher administration that historians and geographers will not be able to continue teaching under the scandalous and degrading conditions that currently prevail.”

The “resolution” adds a message directed at me: there is outrage that the Grand Master of the University supports extremist group theories in his statements and questions the value of our teaching. This is a reference to my speeches from the fall and the remarks I make whenever I am interviewed on the radio: students have as much right to demand a reform of university life as leftists are wrong to make it impossible.

The press diverges. Le Figaro, Le Parisien libéré, and Paris-Jour clearly support the moderate students. “In the corridors, you could see girls and boys accepting leaflets and leaving with a shrug, saying: ‘We’re fed up with their meetings, their noise; they should do it somewhere else.’” “Students who have no other ambition than to work in order to attempt their exams are becoming increasingly exasperated by the political agitation maintained in the faculty.”

In contrast, Combat does not hide its sympathy for the “revolted.” “The term ‘enragés’ may be excessive when applied to young people whose rebellion stems from concern and whose ideals are not without generosity... Adults, and particularly those responsible for education, should show a bit more concern for the youth, which has no reason to be a perfect reflection of its parents’ generation. (...) But perhaps a society has the University it deserves. And beyond the University, it is society that needs to be questioned.”

Dean Grappin is encouraged by the meeting of moderate students and by the resolution from the history professors.

Bourricaud provides me with a written account of the day's events and draws the following conclusions:

“A draw and ‘suspense’: this is Mr. Grappin’s impression of the day. The worst has been avoided. For the dean, the most important thing is that events proceeded calmly, if not in an orderly manner. It seems as if unofficial contacts had been made to work out a modus vivendi. The protesters committed to sticking to the rooms allocated to them, without attempting, as they had initially intended, to spread out freely into all the rooms and auditoriums. This gentlemen's agreement having been respected, a sort of coexistence was established between the two faculties, that of Cohn-Bendit and that of Dean Grappin.”

Nanterre, Wednesday, April 3, 1968.

Dean Grappin made a statement last night on Europe 1 regarding the exams: “Even if we have to deploy 500 riot police on the campus, the exams will proceed as planned at the faculty. Strict controls will be enforced in the examination rooms. The incidents that have occurred several times recently during partial sociology exams will not be repeated.”

Meanwhile, 27 of the 31 assistant professors of French are calling for the preservation of academic freedom within the faculty, opposing any police presence or intervention on the campus. How can the proper functioning of academic institutions be maintained if we refuse in advance to call upon law enforcement?

A new meeting takes place in the evening: “We do not want permission to be free; we want to be free without permission,” declares Cohn-Bendit. “Culture is the recuperation of creativity as a commodity,” states another speaker. He glorifies graffiti: “From now on, the walls of the faculty should become blank pages where poetry, that is to say, each person's creative violence, can be expressed.”

Sorbonne, Friday, April 5, 1968.

In the morning, the Prime Minister and I meet at the Richelieu Amphitheater. After President of the Guillaume Budé Association, Jacques Heurgon, and Pierre-Henri Simon, we deliver our speeches on Latin and Greek. I have the feeling that we are discussing the sex of angels.

110 rue de Grenelle, the same day.

In the afternoon, a meeting takes place in my office concerning the reorganization of Nanterre and the maintenance of order in the Parisian faculties. I ask Grappin to discuss the situation at Nanterre, the balance of power between Cohn-Bendit and Gallot, and the stance of the “swamp.”

Grappin: “Last week, I was pessimistic, which is why I thought there was no other option but to close the faculty for three days; but the way this week has unfolded, without violence or even incidents, makes me more optimistic.” Rector Roche wholeheartedly agrees and believes the same is true for Paris.

This lingering attitude troubles me. I point out that the “enragés” were 50 on January 26, 150 on March 22, and 300 at the beginning of April, capable of gathering a meeting of 1,000 students who become unruly upon hearing a German revolutionary leader.

Why not take advantage of the upcoming Easter holidays to undertake a decisive action by closing the residence?

The rector and the dean, supported by Laurent and Olmer, agree that the residence is a weak point on the campus. It is where movements are born or regroup. However, cleaning out the residence would currently be impossible without damage. It must be done during the summer vacation.

The action to be undertaken immediately after the Easter holidays before the disciplinary committee and the University of Paris council seems to be the maximum feasible. It will lead to the expulsion of about fifteen “enragés” from the university and the deportation of Cohn-Bendit to Germany. This would be a strong deterrent. We cannot go further before the summer dispersal.

Dean Grappin makes two proposals:

Create a university security force: men robust enough to act on campus like peacekeepers in the streets or bouncers in nightclubs;

Establish a disciplinary committee for each campus, endowed with the powers previously held only by the university council, which is too numerous and whose procedures are too cumbersome.

I fully approve of these two proposals. It is agreed that the necessary time for the texts, funding, and signatures will prevent these two innovations from being implemented for the Easter semester; they are to be added to the set of measures that must be put into action by the end of June: cleaning the residence, expulsion of the illegal occupants, allocating part of the residence to teaching, changes to the status of the residence and campus.

As for the exams, they will be held at the Palais des Sports or at CNIT. Those who refuse to attend the exams will lose access to the university services and will be barred from returning to Nanterre in the fall. Those who disrupt the exams will face immediate procedures and will be permanently expelled from the University.

Paris, Saturday, April 6, 1968.

Jacques Aubert, the Secretary General of the Police, informs us that a file on Cohn-Bendit regarding the Cinémathèque affair should provide the basis for an expulsion operation. We confirm that we naturally have no objections.

Paris, Friday, April 12, 1968.

Pelletier, my chief of staff, contacts Aubert to check the status. He is informed that the police have had to negotiate with Cohn-Bendit to ensure that the demonstration planned to protest in front of the German embassy against the attack on Dutschke proceeds peacefully. It is impossible to expel someone with whom one is negotiating.

Paris, Thursday, April 18, 1968.

Domerg complains to Pelletier about Grappin's laxity. He emphasizes that if this approach continues, we will face an irreversible situation. Pelletier responds that the motives of the agitators go far beyond the university: ultimately, firmness means sending 500 CRS1 to Nanterre; the decision is beyond our control.

Today's police report states that UNEF is calling for a demonstration tomorrow evening in the Latin Quarter. It thus joins the initiative of the JCR led by Krivine. One can be concerned about this rapprochement between UNEF and JCR, which are the most active leftists and closest to the “enragés.”

During a meeting held in Nanterre, Cohn-Bendit criticized the French Communist Party for “supporting students and Vietnam only with fine words,” and announced that tomorrow's demonstration in the Latin Quarter “will be marked by acts of violence.”

The Union of Communist Students is preparing another demonstration for Monday, April 22, “against American aggression in Vietnam.”

It is also peculiar that we are being informed by the police prefecture about meetings taking place in university buildings. I ask Pelletier to request that the rector and deans notify us of meetings that are becoming completely unacceptable.

Friday, April 19, 1968.

It is both the resumption of studies after the Easter break and the beginning of the protest season.

In the Latin Quarter, a spontaneous demonstration gathers between 1,500 and 2,000 activists led by Cohn-Bendit, Krivine, and the leaders of the CAL (Student Action Committees). Seven red flags lead the march, and three black flags bring up the rear. They parade throughout the Latin Quarter, as if to take possession of it. A few projectiles are thrown at a police car. The Ministry of the Interior does not seem to be disturbed.

Sixteen professors from the Faculty of Letters at Nanterre, known as the “hawks,” sign a motion threatening a strike if order is not restored: thus, the only resistance considered or conceivable would be to stay at home! The hawks are not about to pounce on their prey.

Sorbonne, Sunday, April 21, 1968.

Extraordinary General Assembly of UNEF, held from 3 P.M. to midnight in an annex of the Sorbonne. This is the major confrontation between two irreconcilable factions.

After a day of verbal and physical violence, only the intervention of the police managed to separate the opponents. Under police protection, UNEF delegates left the hall at midnight without having been able to complete their work.

The UNEF president, Perraud, resigned “for personal reasons.” In reality, because the national board found him too weak. The current vice-president, Sauvageot, who does not face the same criticism, will temporarily replace him until the next general assembly, scheduled for June.

Nanterre, Monday, April 22, 1968.

The academic year is in full swing! A partial sociology exam takes place in disorder. A report from the police describes: “In the first hour, students worked together, and around 3 P.M., the professor announced that the exam would be conducted with the aid of photocopies. These documents were delivered to the candidates by UNEF officials, allowing everyone to continue their work with the course material in front of them.”

Grappin takes control of his council again: he persuades his fifteen “hawks” to withdraw their motion. No ultimatum, no threat of an absurd symbolic strike.

April 22-25, 1968.

In the Latin Quarter, Occident vandalizes the UNEF headquarters on the 21st, the Comité Vietnam national's offices on the 22nd, and throws a grenade into the UNEF offices on the 24th.

On the 23rd, the leftists retaliate by vandalizing the FNEF offices and do so again on the 25th. A student, a member of FNEF, Hubert de Kervenoaël, is assaulted, injured, and robbed. He files a complaint against Cohn-Bendit, who is alleged to be the leader of the commando.

Whether in Paris or in Nanterre, Cohn-Bendit has become a sensation: his outbursts, interspersed with pranks, inflame the lecture halls and provoke laughter. How dull and boring the professors seem in comparison!

Paris, Tuesday, April 23, 1968.

Today's police prefecture report revisits the UNEF general assembly. It humorously notes: “On March 17, for a meeting in Colombes, the UNEF national board had to seek the assistance of orthodox communists to thwart the efforts of CLER activists. Paradoxically, it was these same CLER activists who, on April 21, provided the security for the general assembly. This reversal highlights the progress, in just a few weeks, of revolutionary elements within UNEF, which they now practically control.” This situation concerns the note's author, who seems to hope for a resurgence of control by the Communist Party.

Nanterre, same day.

The organizing committee of the “March 22 Movement” writes to Dean Grappin:

“Dear Dean, the March 22 Movement has decided to hold a general meeting on Friday, April 26. Consequently, it will occupy Amphitheater B1 from 2 PM, as it is the only one capable of accommodating all its members. We kindly request that you ensure the amphitheater is available for this purpose.”

Thus, Cohn-Bendit issues his orders to the dean, selecting his amphitheaters: Dean Grappin will have no choice but to comply.

Nanterre, Friday, April 26, 1968.

In the afternoon, at Nanterre, Cohn-Bendit prevents a lecture by the communist deputy Juquin from taking place in an amphitheater where 150 students have gathered, but where orthodox communists are in the minority. Cohn-Bendit greeted Juquin, who shook his hand: “What an event, a communist shaking hands with a leftist.” Juquin responded, “I am not shaking hands with a leftist, but with a student.” He was unable to speak and had to leave the premises, white with rage, telling journalists: “I will come back, I assure you.”

On the other hand, Cohn-Bendit allows a lecture by Laurent Schwartz to proceed in the amphitheater nicknamed Che Guevara. Schwartz began with: “Comrades, revolutions always start thanks to students.” Cohn-Bendit then called him a “bastard” due to his stance in favor of selection in faculties.

Laurent Schwartz confides to a France-Soir journalist, Nicole Duhot: “I don’t understand anything; I wonder what these students want.”

Do they know themselves? Claude Gambiez of Le Figaro reports Cohn-Bendit’s comments: “Many divergences are breaking out from all sides. The demonstrations will regress due to the exams, because students are afraid of failing.” Cohn-Bendit doubts he will succeed in boycotting the exams.

But here comes support from the teachers. The SNESup-Humanities section of Nanterre votes for a motion in favor of a “critical university” in the German style:

“The student movement expresses a real and general crisis of our societies. The current University is characterized as a class University. (...) The critical academic practice is inseparable from a generalized critical social practice. It must be articulated with all other aspects of class revolutionary struggle, primarily with labor struggles.”

Friday, April 26, 1968.

In Nanterre, the “Mouvement du 22 Mars” distributes a Bulletin No. 5494 bis (sic) that is very explicit about the ideology and ulterior motives of the “enragés.” After twenty pages that exalt anti-imperialist struggles, struggles in Eastern countries, creative culture, the critical university, and condemn conservatism, false revolutionaries, and police repression, the Bulletin provides the recipe for a Molotov cocktail.

3:00 PM.

The leftists have expelled an English professor and his students from an amphitheater to hold a demonstration there.

Is this the last straw?

The Prime Minister has asked me to act with extreme firmness. He said to Domerg: “What are we waiting for to deport Cohn-Bendit?”

Pelletier reminds Domerg that after the occupation of the administrative tower by the “enragés” on March 22, Fouchet agreed to proceed with an expulsion only if it was preceded by an exclusion from the university, a procedure that is cumbersome and slow. It is currently underway but will not be completed until around May 10.

Pelletier calls Nanterre to check on the progress of Grappin regarding the preparation of exclusion files for the disciplinary council. Grappin is not available. The assistant, Beaujeu, answers. He knows nothing about the exclusion procedure. Thus, Grappin, who is aware that his faculty council is hostile to any such measures, has not dared to inform his own assistant of the procedure he was supposed to implement. And he is a courageous man... deported by the Germans because of his courage.

Pelletier calls Rector Roche and asks him to file a complaint against the publication of the Molotov cocktail recipe.

4:15 PM.

Pelletier reports to Matignon. Jobert will involve the Places Beauvau and Vendôme regarding Roche's complaint, which should officially reveal the names of those responsible for the Bulletin. This will allow for both disciplinary and legal action against them.

4:30 PM.

Roche informs Pelletier that the complaint has been filed with the prosecutor.

Saturday, April 27, 1968.

In the late afternoon, upon arriving in Chambéry for a conference on higher education planning, I am astonished to learn from Pelletier that preparations are being made to release Cohn-Bendit, who was arrested this morning near his home on the complaint of Kervenoaël and Roche.

I immediately call Joxe: “How can you release Cohn-Bendit now that you have him? This Kervenoaël has dared to do what neither the university authorities, nor the police, nor the judiciary have dared to do in three months. The criminal police have been questioning Cohn-Bendit all day and have not managed to find any serious charges against him? It means they don’t want to find them.”

Joxe takes a somewhat condescending tone: “We are not in a banana republic. To arrest someone, we need evidence of their guilt. This Kervenoaël claims that Cohn-Bendit threatened him with death, but Cohn-Bendit denies it. In the scuffle where Kervenoaël was injured and had his wallet stolen, Cohn-Bendit insists that he only intervened to help him. As for the Molotov cocktail recipe that appears on a page of a bulletin from his group, he laughed loudly and said it’s a hoax.”

AP: “But the hoax is claiming to the police that it was only a hoax! He has distributed thousands of copies of a method to set vehicles on fire, which is commonly used by his allies from the German SDS. According to what my officers have told me, this recipe is the real deal! It would be a hoax if it suggested mixing water and flour, but it specifies how to mix gasoline and sand and even the length of the fuse. It’s nothing like a hoax. It’s a clear act of terrorism. And isn’t the State Security Court meant to handle such crimes? It’s been almost four months, since the beginning of January, that I’ve been demanding his expulsion, and every time, excuses are found to avoid it! Do we really need to be so cautious about expelling a foreigner residing in France as the leader of a revolutionary movement?”

Joxe ends the conversation: “Listen, I’ve just had a long discussion with Fouchet, and Pompidou himself shares my sentiment. Pompidou told me in no uncertain terms: ‘We cannot allow ourselves the ridiculousness of incarcerating a student who has committed a prank.’”

Discouraged, I hang up. If I call Fouchet, he will tell me that he is still adhering to our agreement, meaning that he will expel Cohn-Bendit as soon as he has been condemned by the university jurisdiction, since what he is accused of takes place within the university premises. And if I call Pompidou, he will not be able to reverse his decision after having rendered such a verdict. There’s really nothing more to be done. This Cohn-Bendit is truly elusive!

Matignon, Monday, April 29, 1968.

After discussing the schedule for reforms, I talk with Pompidou about the schedule for agitation.

AP: “My plan is to hold out until mid-June, trying to avoid the worst while taking all necessary measures to deploy the police if the students come to blows. In the meantime, the disciplinary procedure will proceed, and when Cohn-Bendit, along with his seven comrades, has been sanctioned by the university council and stripped of his student status, he will be escorted to the border.”

Pompidou gives me the impression of being very cautious, even though last week he expressed his keen frustration over the troubles in Nanterre:

“Yes, Fouchet and Joxe called me on Saturday about Cohn-Bendit. It was difficult to hold him since we didn’t have any obvious evidence.”

For the upcoming term, I outline the measures I am considering:

— Evacuate the university residence, detach it from Nanterre University, and open a technical institute (IUT) there;

— Relieve Grappin of the vice-rector functions he is actually performing; at the start of the term, appoint a strong-willed deputy rector to head the entire Nanterre University.

Pompidou warmly approves these two projects.

On educational reforms and relations with the youth

Restricted Council, Thursday, April 4, 1968.

The time has come. The General in the Restricted Council must finalize the selection process. I present my plan, which everyone around the table already knows.

An inter-ministerial council chaired by Pompidou at Matignon on March 26 allowed for better determination of the points of contention. The Prime Minister does not want entry “quotas” to be publicly displayed. He prefers a more discreet system: the rectors would provide the faculties with “specific but unofficial” indications about the numbers to be admitted. I align myself with this fragile hypocrisy.

Our views on the baccalaureate also differ: Pompidou wants to maintain this barrier that still holds; I wish to gradually turn it into a tool for guidance, shaped throughout the second cycle. But this evolution will be slow, and the baccalaureate as it is can serve temporarily: I am willing to acquiesce, though not without defending my idea before the General.

More delicate is the issue of an appeal examination for candidates rejected based on their files. Pompidou insists on it, because an examination “cannot be questioned.” I fear it, as its rigidity undermines the informal flexibility of a contract between the university and the student, flexibility which seems to me to be the only way to humanize the harshness of the selection process.

The General opens the discussion on the simplest subject: “de-stocking.”

CDG: “The intention is good, but the implementation is questionable. Who will decide to stop re-registering confirmed unfit students? Your academics. Will they do it? Won't they grant exemptions to everyone?”

Pompidou: “On the terminology, let's avoid talking about stock and de-stocking; these are not goods. On the substance, I share your concern. We can toughen the system by reserving exemptions for the rector on the proposal of the dean, in precisely enumerated cases: illness, etc. There is nothing regarding disciplinary breaches or expulsion procedures.”

AP: “That would require another decree. I can think about it.”

CDG: “Good. Let's move on to the main point: university admission.”

Debré (leading the charge): “First, a general observation. There are twice as many students in France compared to the population, and even compared to the number of young people. There are half as many in England; the same in West Germany. This wildly expanding university system is a danger to the nation. We must reduce the number of students starting this year.”

AP: “It would not be reasonable to cut the number of students in France by half. What is reasonable is to slow down the rapid growth we have seen over the past ten years and to slow it down even more in fields with limited career prospects. This is already a huge shift in mentality. We can indicate the way, set the principles, and undertake a gradual implementation. Stopping inflation, yes; but we cannot undertake a brutal deflation!”

“We cannot prohibit baccalaureate holders from enrolling in university without offering them an alternative; namely, the possibility, while entering the workforce, to study part-time, by correspondence, through audiovisual means, and evening classes, which is much less expensive per student than regular studies.”

Debré: “Less expensive, that remains to be seen; it will create a vacuum. People will flock to enroll, demanding resources, which will lead to a resurgence of university inflation. It’s true that we cannot close the universities to baccalaureate holders and not take care of them. But we must not end up with something that costs more than this waste.”

“The baccalaureate, you maintain it but strip it of its value. I understand moving the baccalaureate towards a school performance assessment, a certificate of completion. But then, we lower the only existing barrier. Organizing an entrance exam is materially very difficult. Plus, it will inevitably create a preparatory year. That would guarantee inflation! Setting quotas? But on what criteria? We would need to diversify the faculties, create technological universities, but that’s costly, very costly!” (I sense he is negative and uncertain, which pains me.)

Pompidou: “The question is about entry into higher education. We cannot decide to abolish the baccalaureate as an access system. That would be brutal. Moreover, we cannot handle 180,000 candidates for entry into the faculties. So I approve of everything regarding preparation for orientation in the months leading up to the baccalaureate, the ‘pre-registration.’ In June, the baccalaureate provides an initial sorting. Baccalaureate holders could enter higher education if they have a distinction, if they are very young, or if they have average grades in all subjects corresponding to their orientation — and in Paris if they live there. That would be about 30% of baccalaureate holders. The rest submit their files: the institutions decide. For those who are not accepted by any faculty, we can foresee an entrance exam in the faculties where there are remaining places.”

“What are the alternative pathways? There are the chambers of commerce programs: sure. There are the IUTs: they need to be developed, but they should not be the refuge of rejects. They should have the image of semi-grande écoles.”

“Then your part-time university? I am opposed to it, except for those who have had a job for at least three years. In that case, it becomes social promotion.”

“The resit exam for entering the faculties should be in September, which means removing the second session of the baccalaureate. Otherwise, preparatory classes would reappear.”

Debré: “It’s not the first time someone wants to abolish the September session! But the baccalaureate is a huge injustice, and you will be forced to reinstate the second session.”

AP: “The baccalaureate is a huge injustice because it is a one-time event. We can improve it gradually. We can transform it bit by bit into a baccalaureate assessment that would specifically facilitate the orientation of young people and the decisions of the faculties. I agree with refining the selection criteria: distinction, average grade; we can, moreover, combine these criteria. But I insist on the necessity of opening up part-time university education. It will not cost us more, but less. Since those who will be admitted are currently admitted into full-time faculties. It’s an essential consolation prize. We already have a prototype in the distance education in Vanves.”

Pompidou: “It's not just about saving money. We want to avoid having people working for nothing. Your idea is essentially vocational training...”

AP: “We would only open these universities for certain disciplines and under specific conditions, the first of which would naturally be having a baccalaureate.”

Debré: “Full-time university is already a part-time university! What will it be like!”

CDG: “Why dismantle the baccalaureate?”

(He didn’t like my idea of evolving from the baccalaureate exam to a baccalaureate assessment.)

“It’s a barrier, and it creates motivation. We can use it as a criterion, with age conditions. We can also consider grades by subject. And for others, aptitude can be assessed by university councils, with your pre-registration system.”

“However, I don’t believe in part-time universities. I prefer that we administer an exam to a small number of people after two or three years in the professional world. There should be a baccalaureate session in September.”

Pompidou: “I insist on having an exam that allows revisiting a negative decision from the university.”

AP: “I am against a re-examination. It would undermine everything. We can question doubtful candidates with tailored tests or in an interview, but not through a formal exam. We must not recreate a system of rote learning.”

Pompidou: “Interviews are deceptive.”

AP: “Let’s not forget that to be refused, it would require that four juries, in four different faculties, have said ‘no’! As compensation for my strictness, we need something presentable: part-time universities. Let’s at least adopt the principle.”

Pompidou: “In this part-time university, you will have a huge influx of people. Let’s specify that it can only be for law and literature. And that it does not prepare for the degree!”

AP: “I agree.”

CDG: “No university diplomas!”

The General summarizes his decisions: “The baccalaureate is maintained and its value preserved. To enter university, candidates will make formal requests. Admission will be automatic for those who have obtained the baccalaureate under good conditions of level or age. For others, their aptitude will be assessed by a jury specific to each institution, possibly with verification tests. The creation of new IUTs (Instituts Universitaires de Technologie) will be accelerated. New training opportunities will be offered to young people not admitted to higher education. For the organization of schooling, the minister's proposals are accepted, but exemptions will only be granted by the rectors.”

"In total, it will be a significant progress to direct students towards various, appropriate pathways, rather than just enduring the current system. A bill is therefore being prepared for this session."

I have saved the principle of the open university but have significantly emptied the shell. Pompidou has adopted the idea of automatic entry for the best baccalaureate holders: I don't mind that. I managed to avoid the introduction of a re-examination, which would have undermined my approach based on the contract. The General, following Debré, seems to have maintained the second session, which complicates everything.

After the restricted Council meeting, I get into the Prime Minister's car. He gives me his approval for the imminent departure of the Secretary General and his replacement. I present a new project — a model university, selective and competitive, to be opened at the start of the 1968 academic year, with voluntary teachers and quality students, all committed to developing a new higher education program together: “Why not choose to open it in Nanterre? In any case, significant work is needed there to erase the signs of vandalism, sow lawns, plant shrubs and flowerbeds, to improve this bleak environment. We could take advantage of the vacation period to ‘clean the casbah,’ meaning the residence, where all sorts of undesirable people live. At the start of the year, we would only take back the students who have successfully passed their exams, and we would carefully select first-year students. We would treat the first cycle like preparatory classes in high schools. It would be an experimental university, a center of excellence whose model would progressively expand in the following years if it succeeds.”

Pompidou seems very interested. Once his car stops in the courtyard of Matignon, he remains there; the driver and inspector step away. He reflects for a moment, then concludes: “For the following years, we will see. But I agree that you should make arrangements for the start of the year at Nanterre.”

[…]

Council of April 24, 1968.

Approval of the “individual measures” gives me the floor to present the appointment of the first director of the ONIOP, André Bruyère. The General hesitates, as the decrees establishing the Office have still not been issued.

CDG: “Naturally, you will only announce his appointment after the publication of the decrees.”

Pompidou convinces him that it is a matter of a few days and that it is good to officially get Bruyère to work.

But I am especially waiting for the moment of communications. Nothing should leak from my presentation on the selection process before I convene the bodies that are supposed to inspire our decisions. We cannot put the Capelle commission in a position where it is faced with the completed fact: I need to make it my ally by showing that the government is following its recommendations. The same goes for the deans of the five faculties, along with their advisors, from whom I need to gain approval, while they are still unaware of the details.

Addressing all my colleagues, at a moment when student agitation is beginning to spread political unrest, I outline the ins and outs of the ongoing reform. I describe its modalities, which are still open: “Before the baccalaureate, there will be information and orientation operations and the creation of an academic file; after the baccalaureate, automatic enrollment for certain baccalaureate holders; for others, examination of the academic file by institution-specific juries; for doubtful cases, a verification exam.”

“Controlling access to universities is not a Malthusian policy but a condition for a policy of university expansion. It is not about restricting the total number of entries into various forms of higher education; it is about normalizing their growth within reasonable limits. Our country must be able to support a student load with a total number that is regularly increasing, provided that this load is properly distributed between educational programs that can jointly match students' aptitudes and national needs.”

CDG: “Avoiding submersion and waste is what needs to be done. The submersion of universities. And the waste of young people who enter the faculties but are not capable of succeeding, who do not achieve anything. It is a major task to clear the faculties of such students.”

“There are also those who are not admitted to the faculties at the moment: they should have the possibility of appeal. For them, we need to provide facilities to obtain higher education, but practical — higher vocational training.”

“As for the IUTs, they have made a good start. They are increasingly appreciated. They need to have their own character. They are not substitutes for the faculties.”

Pompidou: “We are pragmatic. We are not setting up a barrier. We are not conducting a classical exam. We are implementing an orientation system, which is based both on individual abilities and employment opportunities.”