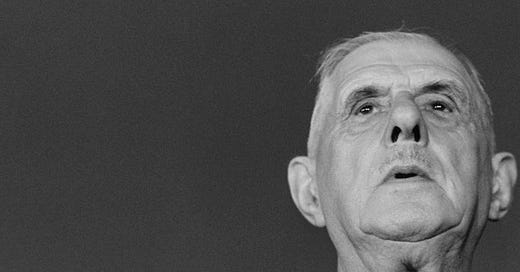

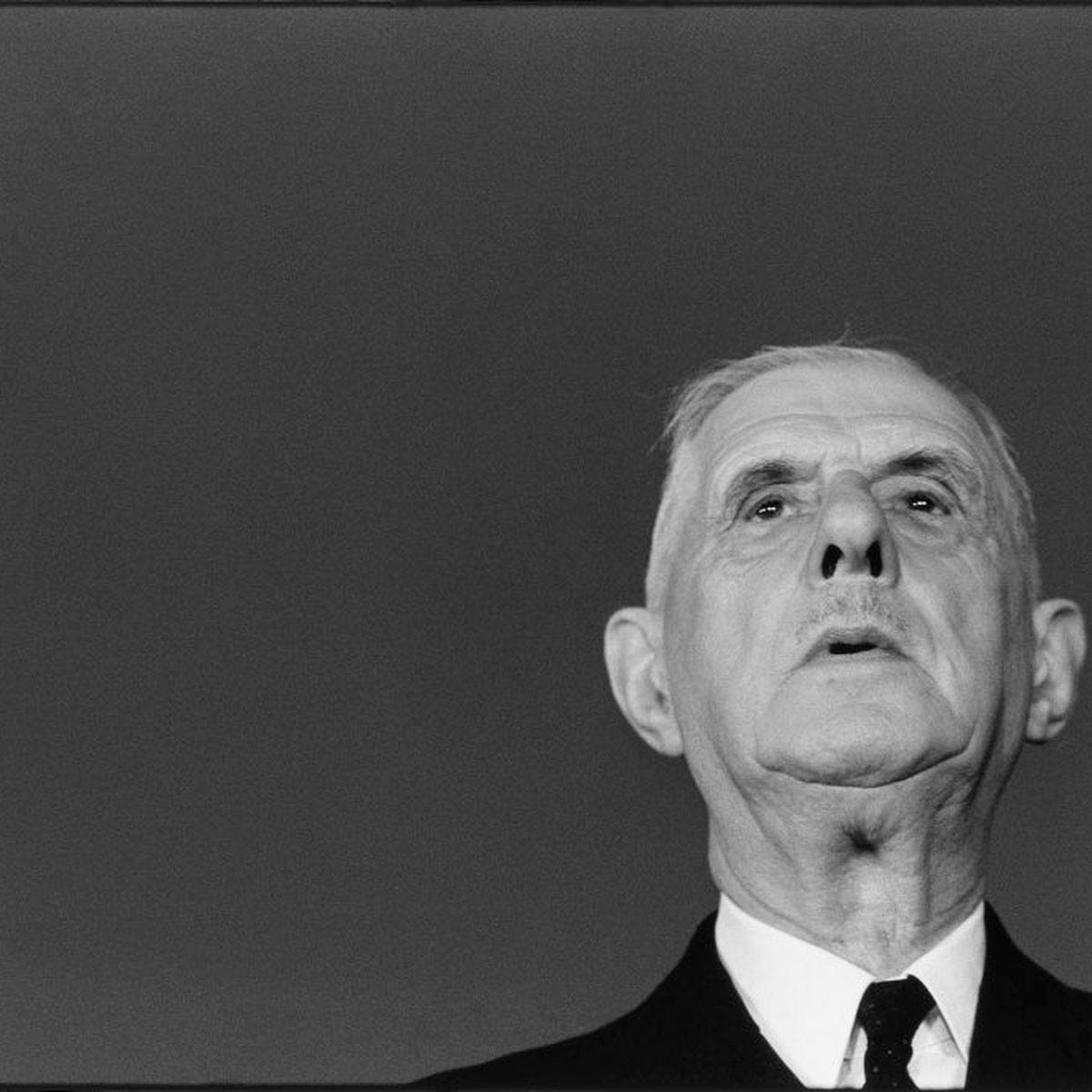

De Gaulle summons Peyrefitte for farewell visit

Provins, Saturday, June 1, 1968.

When Xavier de La Chevalerie calls me in Provins to ask me to come to the Élysée for a “farewell protocol visit to the General” on the afternoon of Pentecost Sunday, I initially decline the invitation: “I organized a celebration at the same time for the garage owner in Sancy-lès-Provins, you remember, the one who smashed Geismar's convertible. I really don't want to cancel it. Besides, how can I find enough gasoline to make the round trip to Paris? Please excuse me to the General, but I am facing a material impossibility.” La Chevalerie hangs up without arguing, but without hiding his surprise.

Then, upon reflection, I tell myself that I cannot sulk at an invitation from the General. His letter from Tuesday touched me. I cannot respond in such a cavalier manner. I arrange to move Maurice's celebration earlier, to find some gasoline, and to ask the aide-de-camp to add my quarter-hour to those of the other dismissed ministers…

The gasoline: I later learned that the General, at the end of the Council on May 30, had uttered this sibylline phrase: “We must carry out a gasoline operation.” The “gasoline operation” had been set up in the strictest secrecy by Guichard, the Minister of Industry, and André Giraud, his director of fuels. They had concentrated significant reserves of the precious liquid in Bois de Boulogne, to release them only at the opportune moment. It was therefore the General who gave the green light at the precise moment it was needed, so that Parisians could regain the freedom to take to the roads for an almost normal Pentecost on May 31. The General had regained his commanding instincts.

Salon doré, Sunday, June 2, 1968, 7 P.M.

The General must be tired from having devoted his Pentecost weekend to ten executions. Yet, he does not seem rushed, as the four “institutional” figures of the evening are not there on Sunday to report to him.

CDG (paternal): “In a great crisis like the one we have just gone through, the battle quickly wears out men. It is normal, after such a shock, to relieve the men who have been in the thick of it. I have always done this, even for much lesser shocks, since I have been in office. It is like in combat. A unit that has been heavily engaged is brought to the rear, while the reserves take its place on the front. You were relieved first because you were the first on the breach; it was better for you.”

(He must have served the same benevolent reasoning to all those who preceded me, even if the last sentence is more personal.)

AP: “I do not dispute your decision at all. I spontaneously offered, after the first night of the barricades, to put my portfolio at your disposal, in case you judged that a change of personnel in this position would help resolve the crisis. After hearing the Prime Minister's speech that same evening, I wrote to him to give him my resignation outright. Since the policy he announced was contrary to the one you had prescribed for us, a new minister could more easily re-establish ties with the academics as well as with the students. What surprised me was that it took seventeen days to follow up on this offer, and that my departure was separated from that of my other colleagues who were relieved of their duties.”

CDG (somewhat sternly): “Your resignation was made public a little earlier than the others because you had offered it at the beginning of the events, while none of the others had done so. This relief was necessary, for you and for all those who were engaged in the thick of the battle. But for the others, an occasion presented itself only two days later.”

AP: “What surprised me was that my resignation was announced on the day when everything seemed to be collapsing, when the Grenelle agreements were being rejected by the base, when the Communist Party was demanding a popular government, when Mitterrand was announcing his candidacy for the Élysée… Not only did the announcement of my departure appear as an insignificant detail amidst a national tragedy, but in the political arena, I seemed to be the cause of this general collapse.”

CDG (persuasive): “The Prime Minister had been telling me for a few days that we needed to make some concessions. You were convenient because you had taken the initiative; the others were more difficult because they had not taken the initiative. And then, he wanted to appoint a mediating academic to reconnect with the rebellious academics. You could not have accepted being deprived of your prerogatives. But you should not attach importance to those forty-eight hours. Revolutions move quickly. Events accelerate without anyone expecting them. What matters now is the future. With the age you have, the horizons are wide; whereas for me, the horizon is very near.”

I let a silence pass, then I softly continue:

AP: “What surprised me even more was that the Prime Minister made you accept, on the evening of his return, much more than what I had proposed. He granted all the students’ demands without any concessions, while you had just given me your agreement for a carefully balanced plan.”

CDG (with a weary gesture): “He did not leave me a choice; he put his mandate on the line. If I did not accept his plan, it would have been a regime crisis.”

This is the first time I hear of a threat of resignation from the Prime Minister on May 11, in case the General did not align with his strategy. While Pompidou and his close associates made known the resignation offered by the Prime Minister on May 30 to obtain the dissolution of the Assembly, they were silent about the resignation he might have offered on May 11.

He continues:

CDG: “We had the regime crisis anyway. It might have been better to have it that day. It was the evening when Pompidou reopened the Sorbonne that the authority of the State collapsed.”

No more today than I have ever done in over six years, will I criticize the Prime Minister in front of the General. I remain silent, astonished to hear him pass such a severe judgment on the one he keeps as Prime Minister, in front of someone he does not keep as a minister.

He continues, in a benevolent, almost affectionate tone: “But you stay with me. You are young. You are lucky. I am old. The future is on your side. Think about what awaits you a little later. Prepare yourself.”

AP (to change the subject): “In the end, all it took was for you to snap your fingers for everything to fall back into order! The vast majority of the French did not want this mess.”

CDG: “They did not want it, but they did not dare to oppose those who were causing the mess. They did nothing against the picket lines that prevented the resumption of work. They are ready to let the country deteriorate when determined groups do what is needed for that.”

“The French always have the temptation to give in. How can I prevent them from doing so? It has worked sometimes, in 1940, in 1958, in 1961, the other day. But it cannot always work. I cannot hold the French up all the time. I cannot substitute myself for them. And the French will have to do without me.”

AP: “In any case, they have come to their senses, they have emerged from their apathy. They were waiting to be commanded. They will have, in each constituency, the choice between a candidate who will commit to supporting your government and a candidate who will support those who want to resume revolutionary action. There is no need to worry.”

CDG: “We shall see.”

He ends the meeting:

“I will not keep you any longer. I wrote to you that I have nothing to reproach you for. I repeat, you were caught in a storm where you could do nothing but be swept away by the wave. Now, what matters for the country is to win the elections; and what matters for you is to win yours. An election is a trial. You will not be showered with praise. You will certainly be heavily attacked. Your opponents will blame you for everything and more. For being too harsh and for being too soft. Try to get through it. It's like the ordeals of the Middle Ages. Come back in two weeks to tell me how your campaign is going.”

“If you win, you will have to take on responsibilities in the next Chamber, while waiting to return to affairs.”

For him, the “Chamber” is not the “affairs,” it is the chatter, the endless discussions, the backroom deals. It is purgatory. The “affairs” are the government.

But first, we must elect a good Chamber. Without alluding to my personal case, I reassure him about the overall situation.

AP: “I am not worried about these elections. From the beginning, I felt that the deep country, apart from the organized groups, was not marching for the revolution. You gave the stopping blow on May 30. The people will give the final blow.”

He repeats: “We shall see.”

Superstition? Humility? He does not want to give in to optimistic impressions and leaves the future to God.

This invitation to come back and see him warms my heart. His letter of consolation, it was very much in his manner to send it to one of his ministers on a day when he knew he was grieved. But the invitation to “tell him about my campaign,” I did not expect that.

Peyrefitte returns to the Elysée two weeks later

Élysée, Friday, June 14, 1968.

The campaign is in full swing, and I come to tell the General about mine, as he has not forgotten his promise.

The Odéon was evacuated early in the morning without any resistance. The General will be in good spirits.

In the car, I review my lesson. I would really like to question him about the mysterious day of the 29th. But it is not easy to force a confidence from him. Joxe told me that he tried to “grill” him during his farewell audience: “He sent me packing.” Trying to make him talk so quickly about such a secret subject was obviously a mistake. After fifteen days, will he open up more easily?

Aides-de-camp Salon.

Arriving from Provins, I am well ahead of time, which gives me the opportunity to exchange a few words with Flohic.

AP: “Astoux, who came to record the General's speech on a tape recorder, told me that the General was so tired, his features so drawn, that he looked twenty years older: he was dreadful to see. That's why, according to him, the General did not want to appear on television.”

Flohic: “No, it was surely because he hadn't had time to memorize his text: he needed to read it. In fact, he wasn't as tired as that. He had slept well in Colombey. He was rested, comfortable in his own skin. It was upon arriving in Baden that he looked terrible. He hadn't slept for at least a week, plus the fatigue of the journey. Massu must have thought the General was at rock bottom. That actually served the General. He arrived exhausted, saying: ‘It’s all fucked!’, in order to provoke the reaction: ‘No, General, with your prestige, you can turn the situation around.’”

“I'm telling you all this under the seal of secrecy, although it has been revealed —but incorrectly — by some who want to make people believe that the General simply fled. The General recommended absolute secrecy to me upon our return, and I have kept it since then, even though my superiors have tried to make me talk. Upon returning from Baden, the General told me: ‘I forbid you to say anything to anyone, not even to Pompidou and Messmer. The commander-in-chief is me!’ This is a prerogative he absolutely insists on. He can give orders to any military personnel, bypassing the entire hierarchy. He likes to say that Louis XVI was the first sovereign to give up being the commander-in-chief and that it led to his downfall.”

I tell Flohic that the General took the trouble to write to me on the evening of Tuesday, May 28, when he was supposed to be in a state of distress. No detail escaped him: he knew what he would do on Wednesday, that he would return on Thursday, and that he would see me at the end of the week. This was not the act of a man who is floundering, but of a leader who has planned everything.

Flohic agrees: “On Wednesday morning, d'Escrienne, who was on duty, called me around 10 A.M.: ‘The General asks you to arrive in uniform with a campaign bag.’ Strange, since we were always in civilian clothes to go to Colombey. He wanted me to be immediately recognized by my uniform and able to give orders when landing on a military airfield among soldiers. In fact, this allowed me, at the Baden-Oos airfield, to ask a non-commissioned officer to let me use the phone to call the commander-in-chief: if I had been in civilian clothes, he could have sent me packing.”

“When I arrived at the office in uniform, the General told me: ‘Get navigation maps beyond Colombey.’ I asked him: 'In which direction?' He replied: ‘Towards the east, but make sure no one sees you take them.’ When we left for Issy-les-Moulineaux around 11:30 A.M., the General told me: ‘We must not pass through the quai de Javel, take another route.’ I consulted with the security officers. He said that because of the Citroën strikers. So we had to pass through the right bank. De Gaulle had thought of these picket lines, and we hadn't.”

“As soon as we took off, the General gave me precise instructions: ‘Direction Colombey’, then ‘We are not going to Colombey, we will refuel in Saint-Dizier’, and so on until Baden.”

This escape on May 29 was therefore entirely planned, foreseen in its smallest details, and surrounded by total secrecy. It is the punctual implementation of the precept from The Edge of the Sword about the mystery that must surprise the adversary.

Flohic opens the door to the Salon doré for me. The General stands up, comes towards me, and extends his hand.

The kindness of his smile puts me at ease, but the fatigue that still shows worries me. His wrinkles have deepened. Two weeks after the miracle of May 30, he has not overcome his weariness. He speaks in a lower voice, to the point that I would miss some of his words if the rest of the sentence did not indicate their meaning. He seems exhausted, but at the same time relaxed, probably because of the morning's event.

I congratulate him on the evacuation of the Odéon.

CDG: “What needed to be done has been done. Or rather, has finally been done… It should have been done a month ago, but Pompidou let everything slip. He let go of everything. He let go by opening the Sorbonne without conditions, which led to a contagion of occupations throughout the country. He let go at Grenelle by accepting that the SMIC be increased by 25%, without even asking for it to be done in stages. He dealt a terrible blow to the economy, to the finances, to the currency.”

“Yes, Pompidou has often remained passive. This is not the first time. It is in his character. But I accommodated it. He is a fixer. He lowered the tensions. While Debré caused permanent tensions: he worried. With Pompidou, I was shielded from daily troubles; I could focus on the great affairs and on France in the world.”

I listen to him, astonished. Once again, the General levels a terrible accusation against the Prime Minister whom he has kept at the head of his government. For four years, I had noticed many signs of bad mood, and even many jabs, against Pompidou. Since 1964, I had guessed that he was determined not to let Pompidou run for the Élysée, but to run himself. Since 1965, I knew that he had considered replacing Pompidou with Couve de Murville. But I had never heard such a severe statement.

Yet, how will he be able to replace Pompidou if, as everything suggests, the elections are a success, given that Pompidou appears to the French as the one who best understood the situation and acted best to control it?

It would be unpleasant to continue, or even to let him continue, on this theme. I have other questions.

AP: “I was surprised, on May 30, that you were firing canons at the Communist Party, when for most of the month, it had been the only protection of the State against the leftist excesses.”

CDG: “Well, that was Pompidou's idea… Of course, the communists had no desire to make the revolution until it started. They didn't even want to go on strike. But when people started playing at rioting without them, they wanted to outdo them. They set up trained pickets to paralyze businesses; it paralyzed the whole country.”

“When they saw that it was going so well, that the opposition parties were rushing into the breach to amplify this movement, that the government was reacting more and more weakly, then the communists changed their tune, they started demanding a popular government. (He laughs.) We know what that means, the popular democracies. (He laughs again.)”

“When they realized that everything was collapsing, that the newspapers, the radios, the television were complicit, and that public opinion remained apathetic, what they wanted was for me to abdicate in favor of a so-called ‘left-wing’ regime. At first, they would have been content to be part of it. In the second stage, they would have taken control, while keeping a few non-communist figureheads. You can be sure that they did not want to be outmaneuvered by Mendès.”

AP: “Because they do not forgive him for rejecting their votes for his investiture after Dien Bien Phu, as if they were not French?”

CDG: “Naturally! And it is not Mitterrand who would have prevented everything from falling into their hands! They controlled the streets, the factories, and the public services. With them, it would have been the Prague coup all over again. And, believe me, it could have worked very well, just as it worked in all the countries where they established themselves. First Kerensky, then Lenin. The new government would have owed its existence only to the power of the CGT, that is, the communists.”

AP: “But in Prague, the Soviets were nearby. Here, they are far away.”

CDG: “Not as far as you think. Do not be mistaken. The Communist Party was very close to tipping into insurrection. It had not planned it in advance, it was surprised by the violence of the leftists, whom it had despised until then, and especially by the weakness of the government. Since the insurrectionary strikes of 1947 and 1948, it had renounced violence, because it found that it backfired on them. When it saw last month that the leftists were benefiting from impunity, it completely changed its strategy. What the leftists were succeeding in, it understood that it had the means to succeed much better.”

AP: “Did you really fear that the communists would attack the Élysée?”

CDG: “The communists and the CGT were preparing a large demonstration, the first one that was their own. It was converging on Saint-Lazare, two steps away from the Élysée. For two days, they had been calling for a ‘popular’ government. There was a serious risk that the demonstration would want to storm the Élysée. The first thing to do was to avoid letting ourselves be caught off guard.”

AP: “Is that why you had your son and his family come? You did not want them to be taken, nor yourself to be taken, as hostages?”

CDG: “Of course! My son was locked up at home with his family, and CGT strikers were standing guard under his windows. But above all, I had to ensure the loyalty of our troops stationed in Germany. I had to ensure the loyalty of Massu and his staff. I had to know the state of mind of the contingent. (A silence.) I also had to be sure of myself. And there were many other stakes.”

AP (timidly): “Which ones?”

CDG (a bit gruffly): “I have already told everything to Michel Droit.”

AP: “We were left wanting more… When you boarded the helicopter at Issy, were you decided to return the next day, or to leave without returning?”

CDG: “I had to take a step back. I left all possibilities open. I said all, including my departure. I was assailed by doubt, as has happened to me several times in the past.”

(Indeed, how many times! Not to mention his temptations to “give up everything” during and after the war, which ultimately led to his withdrawal on January 20, 1946, I have witnessed two bouts of depression: after the result, deemed by him to be poor, of the referendum in October 1962; and after the second round of voting on December 5, 1965.)

“I planned to return to Paris the next day after a good night's sleep. But I did not rule out leaving for good. I would have made a final appeal and we would have seen. It would have been an instant referendum. If the French did not want me, well, they would do without me. Too bad for them. You know, they never miss a chance. I have done enough for them. So, I would have gone to Ireland, where I would have stayed quietly. On the contrary, if they agreed to shake themselves, I would have come back to take command. Well, but between these two eventualities, I did not rule out installing the government in Strasbourg, or in Metz. I would have brought my government there; I would have told the French: ‘I have left the capital where, in a few hectares, people have lost their common sense. I have come to this province where people remain reasonable and patriotic. It is from here that we will together restore the State and the institutions.’”

(Thus, he would have resumed his technique of the Rocher Noir: to escape the administration of Algeria from the furnace of Algiers, he had installed the general delegate and the heads of service at a distance, far from the “flytrap” where the street is agitated, where people get carried away, where crazy rumors spread.)

“I would have applied the Constitution.”

(This is his way of designating Article 16.)

“In any case, I thought of making a solemn appeal to the French, if it seemed it could be heard.”

In summary, three solutions: either to restart the “Free France” from the East; or... what he actually did on May 30; or exile, like Charles X, Louis-Philippe, or Napoleon III. It is enough to evoke these fleeing sovereigns to think that the other two hypotheses had all their chances.

CDG: “In any case, it did me good to leave the furnace. When I flew over eastern France, my courage returned. It was enough for me to see Massu, his staff, their composure. The contrast between the agitation of the hornet’s nest and the resolve of the army was striking. Some military leaders let me know that they were determined to crush the subversion if I asked them to. But their messages were transmitted to me by intermediaries; I had not heard them directly. Massu, on the other hand, had not given me any sign. We spoke. He was who he needed to be.”

AP: “But then, General, did you want to rely on the army to reconquer the national territory?”

CDG: “Of course not to reconquer! It was rather the opposite! I had to ensure the army in Germany did not do anything stupid.”

“In May 58, I forbid the army to move: if the paratroopers set out for Paris, we risked the worst: triggering a civil war. It should not have been done neither in 68 nor in 58. So, I had to ensure that the army was ready to intervene if I asked them to, but that they would not do so without my asking.”

“I was ready to leave, but ready to stay. I wanted to see how the army would respond to my call, if I called on them. I wanted to be sure of them and I was not entirely sure, given the way they had behaved a few years earlier.”

AP: “And Massu answered your expectations.”

CDG: “Massu was Massu. He made me feel that the army was not contaminated, that it would obey me, that it would do what I asked of it, but no more, that it would not take any untimely initiative against the chaos. It could set up static guards everywhere, protect the ministries, the prefectures, the train stations, the public buildings. It could reconquer the territory from the strike pickets. Massu restored my confidence in the army and in myself. I did not even need to stay in Baden to wait for the response from the French. An inspection had sufficed. I could wait in Colombey or in Paris for the French to respond.”

AP: "The response came the same day. Pompidou told you, when you called him: ‘You have won.’”

CDG: “Above all, the response was confirmed, after my call, by the procession on the Champs-Élysées.”

A silence, then he continues: “Understand, things were moving so fast that we could not wait for the referendum on June 16 to resolve them. We had to accelerate, we had to ask the French immediately: ‘Do you want me to stay in my post, or to leave?’ It was an immediate referendum. The formal referendum, if it could have been held, fifteen days later, would only have had to ratify the surge.”

“Organize civic action everywhere and immediately”: that was the essential message of his speech — calling on citizens to demonstrate. The referendum, and failing that, the legislative elections, were for later, as a confirmation. But he needed the immediate demonstration that the country trusted him, as he trusted himself.

The General had spoken to some — not to me — about “weakness.” How understandable that he let himself be discouraged and still bears the traces of it! He knows that among the most faithful of the faithful, many have abandoned him. He has felt his isolation as he probably never felt it: neither at Carlton Gardens facing the English, nor off the coast of Dakar, nor at the Villa des Oliviers, nor even at the Palais-Bourbon, where everyone voted for him at the end of 1945 without even hiding that they only thought of getting rid of him. Rarely has he been so disgusted by the behavior of men. Fifteen days later, he still seems wounded deep down, refusing to rejoice in a turnaround whose signs are yet so visible everywhere. And then, “he cannot hide that he has the age he has.” The instant referendum of May 30 did not erase everything.

AP: “Wasn't it annoying that this meeting took place in Germany?”

The General raises his chin: “In Baden, we are at home. It is our Headquarters. When the troops of a country are stationed abroad, the military leaders and especially the commander-in-chief can inspect them whenever they want, without having to alert anyone.”

Indeed, during his state visit to Germany in September 1962, the General had gone to inspect, in the camp of Münzgen south of Stuttgart, the 3rd Mechanized Infantry Division in maneuvers. No German troops participated in the demonstration. The military band played La Marseillaise and La Marche lorraine. Mirage jets flew overhead. It was a French affair.

He adds: “It was necessary for the army in Germany to be a trump card, but it was better not to have to use it.”

Then he abruptly changes the subject, as if he did not want to dwell on the mysterious day:

CDG: “So, how are these elections looking?”

AP: “I have never seen any so easy.”

CDG: “Do you really think so? Well, we’ll see.”

I was sure he would say: “We’ll see.” He has never liked optimistic predictions. If only to ward off bad luck, he always tempers them with skepticism. But he said: “Do you really think so?” as if he did not believe it himself. He is more pessimistic than I thought.

CDG: “So, if we win these elections, what should we do afterward, in your opinion?”

AP: “Of course, we must first restore order, since the elections will be held against disorder. But then we must announce generous reforms, make the naive who believed they could change society understand that we are not going to crush them to go back, but that we will make them participate in the choices that affect their lives. This campaign is based on the momentum of your call on May 30; but after the elections, we should place ourselves on the momentum of your speech on the 24th.”

He does not respond, but nods his head, seemingly with satisfaction. I continue.

AP: “Now that the fracture is reduced, the State will get back on track. Confidence will return.”

CDG: “We must not delude ourselves. Many things we have undertaken are being called into question. In this month of May, a planetary event was taking place in Paris: the talks between the United States and Vietnam. It was the crowning achievement of our peace policy. It should have filled all French people with pride. It was spoiled by the chaos.”

“In the country, order will undoubtedly be restored, since now we are doing what is necessary for that. But we must not refuse to hear what has been expressed during this month. There was, after all, a rejection of a system that does not respect the dignity of people. We must implement participation. If we had done it, or at least if we had engaged in it with sufficient energy, I believe we would have avoided this mess… Otherwise, one day, everything will end up collapsing and we will have won only a Pyrrhic victory.”

“You can be sure that this month of May will not be erased from the history of France so soon.”

Nor from his memory.

I believe I can guess that he has lost some of his confidence in himself.

Peyrefitte reflects on his way back to Provins

To these testimonies, one should add that of Philippe de Gaulle, which he has not yet published. He told me the scene — definitely repetitive — of his meeting with his father on Monday, the 27th. It unfolded according to the same provocative scenario: “Everything is falling apart. Nothing is holding. I cannot stay here. I must leave.” His son replies: “If you go to Colombey, it will serve no purpose. The French will think you are going there for a weekend, it will have no effect on them. If you want to regain control of this uncontrollable situation, you must go somewhere other than Colombey.”

Philippe de Gaulle has known for a long time that, to counteract “depression,” one must feed his father's imagination with action, evoke a battle. He launched an idea. It would make its way…

Indeed, after about three hours of uncomfortable travel by helicopter, where he must have ceaselessly pondered the pros and cons of the situation, the General did not have to force himself to play the part of “it’s all fucked.” He put his fatigue, his bad mood, his discouragement, and perhaps even his humiliation at having to be there — seeking advice — into it.

The fact remains that the General entered Massu's house at 2:50 P.M. and gave the order at 4 P.M. to prepare the helicopter for Colombey. Seventy minutes, half of which was used for refreshment and a small part for a conversation with his host: if half an hour of conversation was enough to set him straight, it is because he was not really disoriented.

Flohic, who stayed with Mme de Gaulle and Mme Massu, recounts that the latter said, not without boldness: “One does not reenact a June 18 at the age of 78.” This is a clear sign that she, at least, had not doubted the General's fighting spirit1.

Massu did not have the same impression. But he agrees with Boissieu in the same response: “The army is composed of officers who have devoted their lives to the service of the fatherland and are ready to fight all those who threaten it, both externally and internally. It is also composed of conscripted soldiers who consider the revolutionary students to be shirkers, deferrers who take advantage of the fact that they do not have to serve to sow disorder. If you give the order for the troops to move, they will obey without the slightest hesitation.”

Between his morning conversation and the afternoon one, there was an exhausting journey in the vibrations of a helicopter; but surely nothing that disturbed his two permanent convictions:

The State and France were where he himself was.

He had to be certain that he could rely on the army if necessary to regain control of the situation.

Spending the night in Baden, or in Mulhouse with his son-in-law, or in Strasbourg at the prefecture, or in Colombey, did not matter. The essential thing was to be far from Paris, to sleep well, and to calmly prepare the brief appeal necessary to turn the situation around, inflated with the implications that his displacement allowed.

Exile in Ireland, a stay in Baden, the government in Metz: yes, he considered everything — but what strikes me the most is that, all things considered, it was the scenario that he had, in my opinion, planned as early as Tuesday that unfolded without the slightest modification.

On the evening of Tuesday, the 28th, he informs me that he will not receive me on Wednesday afternoon as planned, but at the end of the week: he had therefore already decided to make his escape.

On Wednesday morning, he announces that the Council of Ministers will not take place but is postponed to the next day at 3 P.M. Why tie his hands, expose himself to having to announce a new postponement, if he thinks of making his stay in Baden? The Council takes place at the scheduled time.

He had worked out a minimum scenario on Tuesday, the outcome of which would be in Paris and within two days. He was certainly open to all other “eventualities,” ready for all improvisations. But he had his program, and it was not dictated by panic.

By insisting that de Gaulle leave his military environment and return to Paris as soon as possible, Massu merely prompted the actor, momentarily troubled, with the text of which he was also the author.

Their meeting was decisive in confirming the starting point of the offensive: not Baden, but Paris. But it would never have been enough to transform a man truly drained of all energy into a leader resolved to subjugate the French. This transformation had its secret within de Gaulle himself.

[…]

I recall what the General told me on September 9, 1964, as he was leaving for South America:

“I could sign decrees aboard the Colbert, just as I could do it wherever a French force is stationed; I could sign them in Dakar or in Baden.”

Like Napoleon reforming the Comédie-Française in Moscow, could de Gaulle have governed France from Baden? It is not surprising that he thought of it. But was this position tenable beyond a few hours? An invasion justified the legitimacy taking refuge in London in 1940. In 1968, where was the invasion? It was internal, and legitimacy could not be reconstructed from abroad.

But de Gaulle could have had this strange idea: to reconquer France from Strasbourg or Metz. Metz, in this Lorraine that Louis XVI wanted to reach in 1791, and from which he planned to reconquer the country by isolating the capital and relying on the province. What a symbol: to succeed in the “flight to Varennes”! Always this obsession with resuming the history of France at the points where it went astray.

Yet, this was not his choice. He knew this constant of our history: regimes are made and unmade in Paris: July 14, August 10, Thermidor, Brumaire, the Three Glorious Days, February 48, December 2, September 4. And provincial revolts have never spread to the rest of the country. Those of Toulon, Lyon, the Vendée, after so many peasant revolts or city uprisings, did not lead to contagion, but were crushed. Henry IV only won when he opened Paris; and it is the descent of the Champs-Élysées in August 1944 that consecrates the call of June 18. It is in Paris, through Paris, that the country is threatened with dissolution. It is in Paris, through Paris, that it must regain confidence.

The General had all the more need to feel the pulse of the army, as Messmer, supported by Pompidou, had worked to rule out any possibility of military intervention.

The army had been pulled out of the Algerian furnace; Messmer had organized this withdrawal; he had oriented the army towards the axis of deterrence. He feared seeing this fine technical instrument thrown into a new political furnace.

This concern had led him to support the strategy of Pompidou, Fouchet, and Grimaud: at all costs, bloodshed had to be avoided, confrontation had to be avoided, appeasement had to be sought. Not only should the army not get involved in this crisis, but one should avoid even mentioning it as a possible recourse.

Dannaud wrote to me ten years later:

“I remember the day when, distraught at having to strip the provinces of all the squadrons of mobile gendarmerie and the companies of CRS, to throw them at Grimaud's request into the Parisian abyss, and aware of the superhuman task we were giving the prefects to hold the provinces with their bare hands, I asked the Minister of the Armed Forces to place at least one infantry section inside the gates of the prefectures and at sensitive points, with no operational mission, but to statically affirm the presence of the State. The Minister of the Armed Forces categorically refused to ‘get the contingent involved.’”

I also ponder these terrible phrases about Pompidou. Are they not unjust?

Pompidou, Fouchet, Grimaud, the three men on whom public order rested, did they really do the opposite of what was needed? If the rifles had fired other projectiles than harmless tear gas canisters, the crowd, after forming a procession behind dozens of corpses, would undoubtedly have wrecked everything, overthrown everything, as it had done in 1830, 1848, and 1871. But if de Gaulle had not alarmed the French with his disappearance and had not galvanized them with his brief harangue, who can say that the revolution would not have prevailed? Together, they had avoided the worst.

Pompidou reflects with Peyrefitte

At the beginning of September 1968, during the parliamentary days in La Baule, Pompidou came, all smiles, towards Fouchet and me, who were chatting. He invites us to lunch in the second half of the month. “It's better to have two tête-à-tête lunches; with three, you don't say anything.” As soon as he walks away, Fouchet whispers to me: “I'm sure he wants to talk to us about May. He is worried about what we might say about it. He wants to charm us and bring us to his side, for fear that we might ratify the severe judgment that the château has on him. You know what the General says to anyone who will listen: that the flood came because he opened all the floodgates wide upon his return from Afghanistan, and that he let everything go again at Grenelle.”

Maison de l'Amérique latine, September 27, 1968.

Strange lunch that brings together the deputy from Cantal, former Prime Minister, and the new president of the Cultural Affairs Commission of the Assembly, who was his minister for six years. We finally have the conversation on the substance that we had avoided — when it would have been useful.

Pompidou first tries to make me talk.

Pompidou: “What is your explanation for this strange phenomenon: why did the same dramas erupt almost simultaneously in universities in the United States and Germany, Italy and Spain, Tunisia and Egypt, Algiers and Warsaw, Prague and Tokyo, Rio and Amsterdam? Even though these are such different political regimes and even civilizations?”

AP: “Everywhere in the world, there is a rapid growth in school and university enrollment. Everywhere, there is a problem of adaptation to a society in transition. Everywhere, a gap is widening between the new generations and those that preceded them. This creates a terrain of frustrations, doubt, and uncertainties. And on top of that, there was a contagion that spread from east to west and from north to south, thanks to very small but very active revolutionary groups in close contact with each other; notably between Germany, France, the Netherlands, and Italy.”

Pompidou: “But in our case, the contagion spread to society. Everywhere else, it stopped at the gates of the faculties. How do you explain that, in such a general movement, France is the exception — that is, it behaves much worse?”

AP: “It is our extreme centralization that we must blame, don't you think? Our system lacks flexibility. Under the Third and Fourth Republics, the government would jump. Under the Fifth, everything goes to the top. Tocqueville said: ‘Only God can, without danger to Himself, be all-powerful.’ A student riot at Berkeley or Columbia, it is the university president who manages the situation, who calls the police or not. No one thinks of blaming the American government, let alone the President. In France, a disturbance at Nanterre or the invasion of the Sorbonne by armed extremists, and the government is on the front line, the Élysée is shaken to its foundations. It is so true that we were not even surprised by it.”

“And then, as I told you when you gathered us upon your return from Kabul: the gamble you took, allowing revolutionaries to occupy the Sorbonne without any concessions, exposed us to the risk of contagion.”

Pompidou makes a dismissive hand gesture as if shooing away a fly: “The element of surprise played in favor of the students. Neither the French people nor we ourselves expected this onslaught. The people had to realize for themselves that these revolutionaries were crazy and that they had to be neutralized. That's what happened. We couldn't avoid this realization. We couldn't do without educating the public, and it couldn't have been done better.”

(He says “the students” — not the “leftists.” I don't point this out; I also don't respond that the element of surprise shouldn't have caught us off guard, since the daily reports from the police prefecture clearly indicated that revolutionaries were preparing a revolution. We knew everything in advance. We shouldn't have confused the revolutionaries with the students, nor should we have spread this confusion through our own language.)

AP: “Today, with hindsight, it seems to me that we can establish the following sequence without error.”

“1) Small leftist groups, originating from the unfortunately fragmented Communist Youth, infiltrated the student milieu between 1966 and 1968. They took the revolution seriously and trained for it.”

“2) Cohn-Bendit, starting in January 1968, coached and galvanized them; he gave them a leader who attracted some and amused others.”

“3) The week of riots, from May 3 to 10, showed that Cohn-Bendit and his ‘enragés’ were ready for no compromise, no de-escalation. They wanted the defeat and discrediting of the government.”

“4) In this climate, the reopening of the Sorbonne was interpreted by the leaders, and those who had been watching from the sidelines, as an unconditional surrender.”

“5) In the following days, the young leftists from Renault-Cléon, Sud-Aviation, and Odéon did the same. The contagion spread.

“6) The PC and the CGT, having failed to eliminate the leftists, understood that they had no choice but to jump on the moving train to wrest control from them. They succeeded. The few hundred leftist leaders were excluded from the game.”

“7) Grenelle almost succeeded, but having failed, it led straight to the end of the regime; the turnaround on May 30 saved us and the legislative elections, which you imposed, ensured the triumph.”

Pompidou: “Of course, the social sector caught fire. It was inevitable. But it would have caught fire even more if we had wanted to maintain a position of strength.”

“There is a very important moment that you do not mention: it is the demonstration on May 13. Its magnitude proved that the working class was in solidarity with the students. But it also drowned them in its mass. It marginalized them. We were back to classic problems. If this demonstration was peaceful, it is because I demonstrated that the government was not the aggressor, but that it was reasonable. I brought the French to my side. Believe me, it was my gesture of appeasement that saved the Republic, and the General along with it.”

“On Saturday evening, returning from Kabul, I told him: ‘For your historical image, you cannot have blood on your hands, the blood of students, the blood of youth. You were unfortunately engaged on the front line by my absence. Now that I am here, let me act. Regain your stature. Stay sheltered from all the troubles.’ That's what needed to be done, and the subsequent events proved it.”

AP: “Between bloody repression and what was interpreted as the victory of revolutionary violence, I think we needed to find a middle ground. You avoided the worst when the crisis exploded. But before the crisis, it seems to me that we could have, if Justice and the Interior had been less timid, quickly neutralized the leaders. We would have spared ourselves weeks of great turmoil, from which we will be long to recover and from which the General may never recover.”

Pompidou, with a slightly annoyed gesture and a somewhat disdainful tone: “One can always rewrite history.”

AP: “Still, if it were to be done again, what would you like me to do — that I did not do; or not to do, that I did?”

Pompidou (he thinks for a moment, without taking his eyes off me): “One thing. When you asked Fouchet to expel Cohn-Bendit and he refused, you should have appealed to my arbitration, because I only found out about it afterward.”

But he is right: the conditional writing of history is vain. He shakes his head: “There is such a disproportion between the insignificance of the causes and the magnitude of the consequences that no intellectual analysis is satisfactory to the mind. I have heard only one rational explanation for these irrational events. An astronomer demonstrated to me that during this spring, there were very powerful solar eruptions, resulting in radiations that affected the most vulnerable people, that is, the young. That would explain this simultaneity in so many countries.”

He says this as if he believes it. I am so taken aback that I prefer not to delve deeper. But this must be his way of devaluing explanations that claim to be rational. He chooses the most delusional one to dismiss them all. He sticks to the irrational — defeated by common sense.

I change the subject.

AP: “How do you interpret the trip to Baden?”

Pompidou: “It's quite simple: he left to never return.”

(I keep to myself, of course, the explanation that the General gave me on June 14.)

AP: “But when he returned in the afternoon to Colombey and called you, you did tell him: ‘You have won.’ So you thought that the anxiety into which he had plunged the French had been effective.”

Pompidou: “It was only effective because he really wanted to leave.”

AP: “Wasn't that precisely his game? Since 1940, how many times has he played it: ‘It's over, I'm leaving!’ He pretended to leave ten times, but he only left once, in 1946, and he saw what it cost him. Don't you think that once again, it was: ‘Stop me or I'll do something terrible?’”

Pompidou: “I think that this time, it was for real... At least according to Massu, who is the best placed to speak about it. And also because of the way he left me in the lurch without informing anyone… Do you realize the situation I was in?”

AP: “But a few hours later, you were reassured.”

Pompidou: “I was reassured for France. But put yourself in my shoes! Imagine the hours I spent! In the morning, he calls me saying: ‘I’m going to rest in Colombey. You represent the future. I embrace you.’ And then he goes to Massu! Do you find that acceptable? I was determined to give him my resignation. I could not accept that he put me in front of a fait accompli… As for the rumor that circulated on May 29, according to which I would have wished for the General's departure, that's absurd! I could only act under his cover. It was essential that he give me, while remaining in office, the means to regain control of the situation. Otherwise, everything would collapse, and the street would win.”

He chews silently for a moment between his powerful jaws before continuing:

Pompidou: “I felt that things were turning when Mitterrand announced his candidacy, according to a procedure that was a coup d'état. He had committed the irreparable mistake. I told the General that very evening: ‘The game is won.’ He replied: ‘You are very optimistic from the beginning.’ I said to him: ‘My optimism was justified! I had announced to you that public opinion would turn in our favor. It has turned. I had announced to you that we would reach an agreement with the unions. I obtained it. Séguy and Frachon made the mistake of not preparing the crowd at Renault, but I can't do anything about that.’ The General had to acknowledge it.”

AP: “Still, the fright that he communicated to the French with his disappearance on the 29th, and then his speech on the 30th, greatly contributed to turning the situation around.”

Pompidou: “Of course. But the General only took note of the turnaround that was already happening.”

“When I took the market in hand for de Gaulle to renounce the referendum and change it to legislative elections, the General corrected the draft of his speech, then handed it to me and made me read it: ‘So, are you happy?’ I replied: ‘Yes, I am happy,’ and we both smiled. I have the feeling that I saved the Republic that day. We were heading for a disaster in the referendum, on the theme: ‘Bonapartist plebiscite!’ And we went to a triumph with the elections, against which no one could rise.”

AP: “Except the revolutionaries, with their slogans: ‘Elections-betrayal,’ ‘Elections-trap for fools.’”

Curious: the General has never spoken to me since then, nor has he ever spoken to anyone to my knowledge, about any pressure that Pompidou might have exerted on him on May 30 by threatening to resign. But he strongly insisted to me on the pressure that Pompidou had exerted on him on May 11, by threatening to resign if he did not accept the “unconditional surrender.” Conversely, Pompidou has never spoken to me — and I do not believe he has spoken to his cabinet — about any threat of resignation that he might have made to the General on May 11, but he insisted on the one that allowed him to prevail on May 30 with his wish for elections.

Who to believe? Both of them, each insisting, as is natural, on what valued them more and avoiding emphasizing what could value their partner.

The conversation turns to the present. One senses that Pompidou is on the lookout for errors and difficulties. If he is merciless toward Couve, it is not to spare the General.

Pompidou: “Politics is not being conducted properly. We have reduced tax exemptions on inheritances while abolishing exchange controls. And we continue to talk about participation without knowing what it means, which is causing panic. We are heading straight for a devaluation, which was inevitable anyway.”

“And then, the leftists are not admitting defeat. Their new slogans are successful: ‘This is only the beginning, let's continue the fight.’ ‘Power is not given, it is taken.’ They are even announcing a ‘red October.’ They are resuming their violent actions.”

“You know, everything the General undertook was based on the idea that the fatherland reconciled the French, beyond their pathological dissensions. But today, we must acknowledge that the young people couldn't care less about the fatherland. Until the First World War, because of the blue line of the Vosges, everyone was patriotic. Between the two wars, there was still the rivalry between France and Germany. Today, Franco-German reconciliation has removed patriotism’s leaven.”

“Do not delude yourself, everything the General wanted to do has collapsed…”

I cannot help but startle: “Oh! Do you really think so?”

Pompidou: “Or at least, everything is shaken. Never had he raised the prestige of France higher than in this month of May when the Americans and the Vietminh came to discuss in Paris. Today, the lessons he gave to the world appear to international opinion as boasts. His attacks against the dollar have become derisory. For the tenth anniversary of his taking power, the balance sheet would have been celebrated worldwide. Today, this balance sheet is presented everywhere as disastrous.”

“What we will have to do when the General is no longer here is to find a compromise between the Republic of the General, with its hard and pure aspects, and the Third and Fourth Republics, with their good aspects. Just as Napoleon established a compromise between the Ancien Régime and the Revolution, which allowed the gains of the Revolution to be saved while ending the disorder.”

Throughout the month of May, I could not stop admiring the skill with which Pompidou reconciled loyalty to the General and his concern for preserving the chances of the Fifth Republic, should the General disappear. But three months after the electoral triumph that the French attributed to him, and after a painful eviction from the government, how his tone has changed!

Dannaud will write to me ten years later: “Without a doubt, Pompidou, like others before and after him, discovered in May the supreme intoxication of the solitary exercise of power.”

On the speech De Gaulle gave on his return

I am not the only one before whom Pompidou boasted of having made the General renounce a referendum he was going to lose, in order to substitute it with elections he was going to win. This version of their meeting, through being repeated and spread, has become like an official truth. It is enhanced by an indication of atmosphere. Between the two of them, only rational arguments would have been exchanged. “I put the market in his hands...”

The expression strikes me all the more because the General, in June, used it in front of me, but in reference to May 11, not May 30. He had kept a very bad memory of the way Pompidou had imposed the reopening of the Sorbonne on him, not at all of the way Pompidou had convinced him to dissolve.

Of these contradictory versions or impressions of the conversation on May 30, which one to retain?

It turns out that the General's papers deposited in the National Archives contain the essential of the answer, in the form of the two successive drafts of his speech.

The two pages of the first document are covered with the General's handwriting. The two pages of the second are typewritten with his handwritten corrections.

In the first document, one can quite easily distinguish a first draft. The handwriting is large, the lines are evenly spaced. A few corrections have been made as he wrote, almost all of them before the sentence begun was even finished.

Here is this primitive version, respecting the layout on the page, line by line, and the crossed-out words.

“1.

I examined the legitimacyBeing the holder of national and republican legitimacy, I have examined all the hypotheses that would allow me to maintain it. I have made my resolutions.”“2. In the present circumstances, I will not change the government. It is capable, coherent, devoted

towardsto the public interest. I will not dissolve Parliament. It has not voted for censure. I have proposed a referendum to the country. It is possible that the maintenance of the present situation materially prevents it from being held. It would be the same for legislative elections. In other words, they intend to gag the entire French peopleas theypreventing them from livingas theyby the same means that they prevent students from studying, teachers from teaching, workers from working, I mean by intimidation carried out by groups organized long ago for that purpose.”“3. France is therefore threatened”

After starting the point 3 this way, he stops. He returns to point 2, in order to conclude it with an essential sentence, which reveals his intention to use Article 16.

“If this situation of force continues, I will take other means than the immediate polling of the country to maintain the Republic.”

To write this sentence, he must skip over the beginning of point 3. He carefully crosses it out, and moves the beginning further down, which is no longer quite the same.

“3. For France is threatened with dictatorship. They want to force it to resign itself to a power

out ofissued from national despair, which would then obviously and essentially be that of the victor, that is to say, that of totalitarian communism. Naturally, it would be colored at the beginning with a less assertive appearance, using the frenzy of wallets and the hatred brought to the regime by politicians of the past. Well! No! The Republicwill not allow itselfwill not abdicate. The people will get a hold of themselves.”“

FreedomProgress, independence, and peace will prevailinalongside freedom.”This first draft has established a structure, a progression, on which the General will not return, and which the numbering underlines.

The approach is clear: I maintain the public powers as they are, which have held firm; but the exits are blocked, the French are gagged, they are being prevented from expressing themselves democratically, through the referendum or legislative elections. The country must therefore regain control, otherwise it will soon be the dictatorship of the Communist Party.

Based on this outline, de Gaulle then proceeded by making corrections and, above all, additions in the margins and between the lines. The manuscript becomes almost illegible, but once deciphered, the enrichments stand out.

The General specifies that he is not resigning. That went without saying. It will go much better by saying it.

He pays a strong tribute to Pompidou to personalize this maintained government and mark the unity of the executive. The General has understood that Pompidou's personality has become a decisive asset. He plays it up. Of the compliments he gives him (“value,” “solidity,” “capacity”), he will have nothing to change.

He develops the objective of the referendum, not wanting to abandon it without defending it: he wants to make the opinion take note that it was both a reform and a democratic way to express support for de Gaulle or his disavowal. Alas, the blocking of the referendum by force was possible; it becomes probable.

Finally, the call to civic action appears, as well as the mission given to the prefects, commissioners of the Republic.

When the General arrives at the Élysée on Thursday at 12:30 P.M.., he calls his secretary and gives her his text to type. The result of this typing, we know: it is the basis of the second document.

However, surprisingly, the typed text is not entirely identical to the General's draft: about a dozen modifications, which do not change the substance but refine the style.

What happened? The General must have rewritten his first, barely decipherable draft (although the secretary is capable of feats), and in the process of this clean-up, which has disappeared, he would have introduced these corrections of an attentive, perfectionist writer.

The General has a quick lunch. When Pompidou arrives at the Élysée at 2:30 P.M., half an hour before the start of the Council, the typed text has not yet been passed on to the General. But he has kept his first draft.

And it is on this draft that he makes, in front of Pompidou, the two major modifications that their conversation will entail. The first concerns the dissolution; the second, the governmental reshuffle.

The General looks for the place where he wrote: “I will not dissolve the Parliament which has not voted for censure.” Above the line, in tiny handwriting, he writes: “dissolve today the Nat. Ass.”; then he crosses out the line below, forgetting in the process to strike out the negation “not” In the conversation, he has finally noticed an impropriety: it is not the Parliament, of course, that he will or will not dissolve, it is only the National Assembly. The Senate is indissoluble...

Moreover, Pompidou has obtained the reshuffling of the government. The General amends his text accordingly, crossing out with a clean stroke what concerns the government and leaving intact only his tribute to the Prime Minister, already so eloquent that it does not need to be reinforced:

“I will not change

the government. It is capable, coherent, devoted towards to the public interest. It is composed ofthe Prime Minister whose value, solidity, capacity, deserve the praise of all.”But he stops there with the corrections. This text is already too muddled to retype. Besides, it is time to go down to the Council.

When he comes out, half an hour later, the typed text is available. He has one hour left to put the final touches on it. He first makes the two essential corrections, those he had already noted on the draft. Then he adjusts the entire text to the new arrangements. The allusion to “another government that would arise from panic” disappears, and is replaced with “He (the Prime Minister) will propose to me the changes that he deems useful in the composition of the government.”

Regarding the referendum, already abandoned, there is not much to change, except to be even clearer. We move from the possible or probable: “I note that the current situation materially prevents it from being held.” But precisely because it is being abandoned at this moment, it is important to specify that it is not being abandoned in principle; therefore: “This is why I am postponing its date.” The previous drafts contained some ambiguity: this time, it is clear, the referendum will not be part of the resolution of the crisis. But it remains in perspective, to address the French malaise at its core.

The sentence about the legislative elections (“It would be the same for legislative elections”) could simply be discarded. But the General is concerned with linking it to what follows, that is, the evocation of the French people being gagged. Masterfully, he rebounds on the question of the delay: “As for the legislative elections, they will take place within the timeframes provided by the Constitution, unless one intends to gag the French people, etc.”

The General still has a little time to improve his text. He loves to write. He has written a lot. He is a man of the written word. And yet, he struggles. “I'm having a hell of a time.” He constantly seeks the right expression and conciseness. It is both suffering and enjoyment.

Could he say that the Communist Party was nothing but a totalitarian enterprise? It is much more than that. The “is nothing but” is too much: “a party that is a totalitarian enterprise.” That is enough.

The General returns to the aid that “civic action” will provide. Aid to the prefects? That is not enough. He adds: “to help the government first, and then locally the prefects…” The government remains the primary impetus, and it is the summit that the base must support first.

Throughout the versions, he circled around the relationship to be expressed between the power that would replace his and despair. His first draft was the simplest: “resign oneself to a power

out ofissued from national despair.” Did he think that this despair conferred a sort of legitimacy? The typed text, on the contrary, seeks to oppose them: “a power that would abuse national despair.” But that is obscure: abuse it for what purpose? It is only at the last moment that de Gaulle finds the right expression: “a power that would impose itself in national despair.”A power of usurpation, whose only source would be usurpation, and to which national despair would pay homage.

De Gaulle now feels his text. He has made it increasingly incisive. He thinks of Mitterrand, Mendès, Lecanuet who are already preparing for the kill. “Politicians on the sidelines,” yes, of course. That will hit home. But he must drive the point home: these politicians, the mask of communism, would soon be its victims: “After which these individuals would weigh no more than their weight, which would not be heavy.”

What is striking is the continuity of the reflection. The primary objective remains the first: that the people regain control and manifest themselves, without delay. The whole reflection stems from the observation that the classic recourse to the ballot, referendum or election, is blocked by the revolutionary situation. His referendum will not be able to resolve the crisis, he knows. He has no prejudice against the idea of resorting to legislative elections. If he rules out this possibility, it is obviously not because the Assembly has not voted for censure, a facade argument. Nor is it because he distrusts legislative elections in principle. It is because he does not believe them to be any more materially feasible than the referendum. But when Pompidou explains to him that neither the supporters of the Fourth Republic nor the communists can obstruct legislative elections, that they have demanded them, that they hold them sacred, that they therefore cannot shirk them, the General is easily convinced. He is quick to grasp that legislative elections are a trap that the opponents have built with their own hands and that he can lock them into it. He is happy to see a possibility of recourse to the people opening up.

The X-ray analysis of the texts shows this luminously, as it can show the touch of a master on an obscured canvas. Pompidou did not have to change the General's mind about the referendum. This did not prevent the General from listening to him attentively, as if his decision had not been made. That was indeed his way, and it could have left Pompidou with the impression and illusion that he had won on this point as well.

On the other hand, it was indeed he and he alone who made the General understand that the feared sabotage of the referendum was not to be feared for the legislative elections. I doubt that to convince him, he had to “put the market in his hands.” The recourse to legislative elections naturally fitted into the General's scheme, as he had sketched it in his first draft in Colombey. It is an easy and useful modification of the tactical arrangement, a clever maneuver that he makes his own.

But the strategy remains the same, that of a battle to regain the confidence of the country in the moment. Without waiting for the electoral deadlines, which the constitutional delays postpone for several weeks. With the assets he has immediately at his disposal: his charisma as a leader, which he feels reviving within him; his Prime Minister, whom he discovers has his own charisma and whom he spectacularly associates with the battle to be waged; the Constitution, whose resources are inexhaustible; opponents, who have made the mistake of showing themselves and evoke a mediocre or worrying alternative; an army without qualms; French people affected in their daily lives by a disorder that they refuse with all their instincts.

This strategy is that of the “immediate referendum.” Two hours later, the demonstration on the Champs-Élysées, by offering him the most beautiful and decisive of victories, will confirm that this strategy was on target.

On these four sheets of paper, history records the General's resolution, the refinement of his approach, the spontaneous place given to Pompidou, and the contribution that the latter brings to him.

To the General goes the credit for having created the conditions for fear and anticipation, for having written this text that resembles a burst of machine-gun fire, and for having delivered it thunderously, in the mystery of a faceless message. To Georges Pompidou goes the credit for having obtained the dissolution and led a revitalized government into battle.

Once again, success emerged from the conjunction of the two men and their unique genius: the tactical flair and realism of one, the inextinguishable ardor of the other.

Once again, the word was action.

AP: “There has been much talk about the ‘voluminous luggage’ brought to Baden. Philippe de Gaulle, a direct witness, assured me shortly afterward that there was none. How could it have been transported? The five seats of the first helicopter were occupied by the pilot, the co-pilot, General de Gaulle and Mme de Gaulle, and Flohic; the four seats of the second helicopter by the pilot, the co-pilot, the doctor, and the security officer; only the fifth seat remained to pile up everyone's luggage, which could not have amounted to much.”