Charles de Gaulle on the Presidency, the Fifth Republic's institutions

From "C'était de Gaulle"

The French system of government is often obscure to the outside world. If the Prime Minister is the Head of the Government, what is the role of the President? Is the President beholden to the Assembly? If the Assembly does not align with the President, how is the country to be governed?

All questions that require understanding the spirit which animated the foundation of the Fifth Republic. Fortunately, that spirit has a great name, was made of flesh and blood, and left us a Constitution along with his confidences on the subject.

Between the fall of the Second Empire and the Second World War, France was governed by a regime of assembly under the Third Republic. In fact, the Third Republic had formed through the indecision of the Legitimists and other Royalist factions who, busy squabbling about such important matters about what the color of the flag should be, gave no other choice to President Mac-Mahon but to hand power over to the Republicans.

Since then, France sunk into the unstable nature of parliamentary politics. An already naturally divisive country saw hundreds of different government succeed one another. Populist uprisings erupted, political impotence gripped the country. And finally, the Popular Front arrived to hand the nation over to the clutches of defeat and dishonor.

With De Gaulle at the helm, this changed entirely. France had someone who could firmly steer the ship. But historical circumstances had propelled this man to his station, what of the future? General de Gaulle was determined to ensure that, while his successors would almost surely not fill his shoes, they would be compelled and required to fully exercise the powers he had.

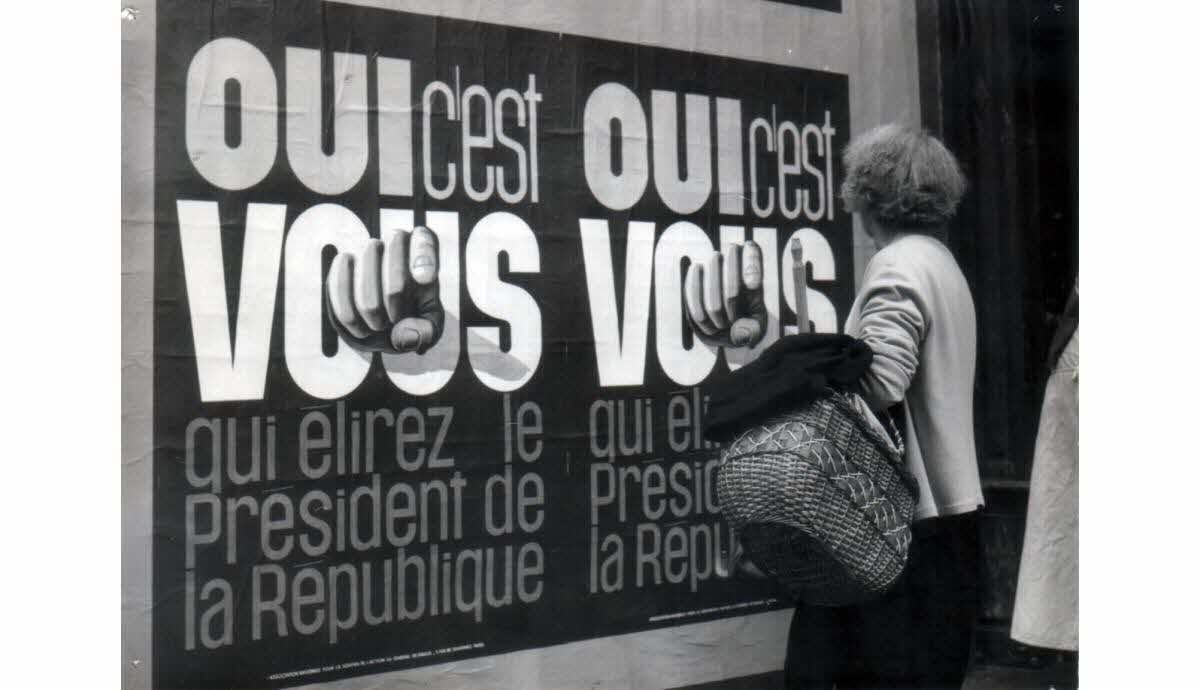

On the necessity of establishing the election of the President via universal suffrage

It was believed, and is still believed, that it was in response to the Petit-Clamart attack on August 22, 1962, that the General conceived the idea of a referendum to establish the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage.

This legend must be dispelled. Fifteen days after the departure of the five MRP ministers, he was determined to push through this reform, which had been germinating since the Bayeux speech of 1946, and which he had long discussed with his close associates (notably after the generals' putsch). It had now become urgent to address the parliamentary insecurity caused by the withdrawal of the only party, other than the UNR, that had so far contributed to the government majority.

Salon doré, after the Council on May 30, 1962

CDG: “Would you please announce that General de Gaulle intends to address the nation on Friday, June 8, via a radio and television address? Indicate that he said that despite the disturbances caused by subversion, despite the attacks in Algeria and even in the mainland, which the public may feel the effects of, the set course is and will be maintained. Regarding the continuity and stability of public authorities, the President of the Republic is determined to uphold them, whatever fluctuations may occur, and will take the necessary initiatives to that effect.”

AP: “You think the continuity and stability of the regime are not ensured?”

CDG: “Well no! Obviously not! You can see what's already happening: all this scheming since the MRP snapped their fingers at us fifteen days ago. For me, it’s different. Legitimacy was conferred upon me by History. Now, legitimacy must be directly conferred by the sovereign, that is, by the people. I will remind them that everything done since '58 was thanks to the confidence the French have placed in me. Besides, on this occasion, I will settle the score with the people of May 13.”

“This confidence has obligated me and supported me day by day. The direct connection between the people and the one who leads them has become, in modern times, essential to the Republic. I will announce that, when the time comes, I will ensure that in the future, beyond the people who come and go, the Republic can remain strong, orderly, and continuous.”

These sentences come out faster, and their style feels polished, unlike his usual spoken language. Without a doubt, he is reciting a pre-written text. He immediately adds: “But don’t disclose that. Stick to the statement I just gave you (he makes me repeat it and approves).

AP: “If I understand correctly, you want to announce that you are going to adopt the presidential system?”

CDG: “No! (He charitably refrains from saying, ‘You haven’t understood anything,’ which must be on the tip of his tongue.) The American-style presidential system is not at all suited for France! Our system is very good as it is! We are simply going to institute the popular election of the President. The French will be the direct source of executive power, just as they are already of legislative power. And if there are any conflicts between the two powers, the people will decide, either through dissolution, through a referendum, or through a new presidential election.”

AP: “It’s a Copernican revolution!”

This expression must seem pedantic to him. Instead of nodding in approval, as he often does when one restates his thoughts, he looks at me as if I’ve committed an incongruous interruption.

He resumes, as if to correct me: “You will see, it’s a crucial turning point. This year will be, in every respect, the year of the great turning point for France.”

(So it was this turning point he wanted to talk about.)

“There will no longer be any speculation about the return of the parties to sabotage the Evian agreements and everything else.”

AP: “But how do you plan to go about it?”

CDG: “By a referendum, obviously! How else do you expect me to do it?”

AP: “Would you apply this reform to yourself?”

CDG: “Of course not! I have no need of universal suffrage election for myself! It will be for my successors. They need to be able to bear the responsibility outside and above the parties. Do you understand? They must be compelled to bear the responsibility. If my successor receives the consecration of universal suffrage, he will not be able to shirk his responsibilities.”

He leans back in his chair and lifts his head. He looks at me from above and afar. He relives before me the history of the Republic:

“When Mac-Mahon lost power because the parties had won the elections, the Versailles Congress chose Jules Grévy, who announced in advance that he would be nothing more than a figurehead. And all his successors of the Third and Fourth Republics were prisoners of this precedent. The abandonment by that lamentable Grévy forced them all to abandon as well, including Poincaré and Millerand, who would have liked to reclaim the presidential prerogatives as fixed in the Constitution. It was too late. The head of the executive was no longer the President of the Republic, but the President of the Council, who wasn’t even provided for in the 1875 texts. The parties, under the Third and Fourth Republics until me, reigned in Parliament as absolute masters.”

AP: “Do you think the universal suffrage election of the President would free him from party pressure?”

CDG: “If my successor receives the consecration of universal suffrage, it’s the only chance he won’t evade the duty of carrying the nation on his shoulders. Otherwise, everything we have tried to do will be swept away.”

AP: “But since you are here and do not intend to apply this reform to yourself, why do you want to implement it now? There is no urgency.”

CDG: “Yes, there is urgency! It must be done by autumn.”

He takes a breath. He hesitates to go further. But he is determined to say everything. He continues:

“First, at my age, you never know what might happen, so all precautions must be taken. And then, if the OAS whacks me…”

AP: “You think no one, after you, could maintain the system you have established?”

CDG: “No one. Everything would be swept away, I tell you, starting with the institutions.”

AP: “Even if it were Pompidou, or Debré, or Chaban?”

CDG: “Even them! And anyway, do you think they would be elected? They themselves would be swept away! The party machinations would return in full force. We need to let the years do their work to consolidate the regime; it's too early for it to stabilize on its own. Look at what the MRP just did: they are preparing to reestablish the third force, as under the Fourth Republic, excluding only the communists and us. All these parties get along like thieves at a fair. And among them, it’s ‘you scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours!’”

He becomes animated as he discusses the future he envisions.

CDG: “But you will see! If this reform is adopted, everything will change. People will no longer bet on the collapse of the regime but on its maintenance. And furthermore, the day I announce it, people will declare themselves for or against it. Everyone will want to hedge their bets against the danger. Once the debate starts, it will become clear that if we win, the successor to General de Gaulle will have as much ability as I do to make the new Republic work. My own power will be strengthened. There will be no more speculation about the resurgence of the party system. The agitations will calm down. Naturally, provided that we win. But one wins nothing if one risks nothing.”

As he shakes my hand, with his other hand on the doorknob: “You don’t say any of this to anyone.”

So here I am, carrying a heavy secret. No one, the General said: so I can't talk to Pompidou about it? Besides, Pompidou is very sensitive. If I break the order I received in his favor, one of two things will happen: either he already knows the General's intention, and he will find it inappropriate that I thought he might be unaware of it; or he will be completely surprised, but he will surely resent me for being the holder of such a significant confidence that wasn't shared with him first. And in both cases, he might think I am failing to keep the secret that I owe to the General.

[…]

After the assassination attempt of Petit-Clamart, political life accelerated. Following the next Council meeting on August 29, I stated, following the General's instructions: “The President of the Republic presented an account of the reflections suggested to him by the attack he narrowly escaped. What the assassins primarily target in the President of the Republic is the guarantor of the stability of republican institutions. What they want is to take his place. Since it is clear that they could not maintain it for long, they would destroy the regained stability.”

“General de Gaulle emphasized before the Council the necessity of safeguarding the institutions. The attack led him to consider that the essential thing was to ensure, whatever happens and without delay, the continuity of the State. He is prepared to take the necessary initiatives. Last week's attack allowed public opinion to become aware of the risks that the Republic had faced.”

During our conversation, he repeated to me, in similar terms, what he had been telling me since May:

“It is essential that my successor not only has the right but feels the duty to take charge of the destiny of France and the Republic. If I were to disappear before this reform is passed, the Fifth Republic would suffer the same fate as the Third after Mac-Mahon: the President would relinquish his prerogatives to Parliament on his own.”

“But,” I ventured, “wouldn't the best solution be for you to have a vice-president, as is the case in the United States? You have introduced substitutes for deputies and senators in our institutions. Why shouldn't the President have his own substitute, given that he is so much more important than each parliamentarian?”

He laughed: “That is indeed a good reason, but only in appearance. Precisely, the President is too important. A vice-president would not be recognized as a legitimate President if he had not been elected as President himself. France is too difficult to govern. The President must be the direct expression of the popular will if we do not want him to be challenged from the moment he takes office.”

AP: “And the assassination attempt will allow you to push through this revision more effectively?”

The General laughed again: “It’s perfect timing.” His thinking hasn't changed at all. However, in the statement he now instructs me to make, the emphasis is entirely on the Petit-Clamart attack. His eagle eye immediately saw the advantage to be taken from popular sentiment. It was crucial not to mention a long-standing reflection: he would have been accused of premeditating the death of parliamentary democracy. It was better to ride the wave of French emotion.

We needed to erase not only what he told me but also what he had me say on May 30th, as well as what he said himself in his speech on June 8th, which fortunately went unnoticed. It was a convincing demonstration of his principle that one always speaks too much…

On September 3, in our tête-à-tête, he confirmed what he had previously told me and concluded with a sort of jubilation: "This year, things are speeding up. We are living through a rush of history."

I felt authorized to let what I had known for more than three months filter out widely, but this time establishing a direct link between the attack and the decision to organize a referendum. The editorialists I met with, and subsequently the entire press, reflected these conversations, where I went quite far.

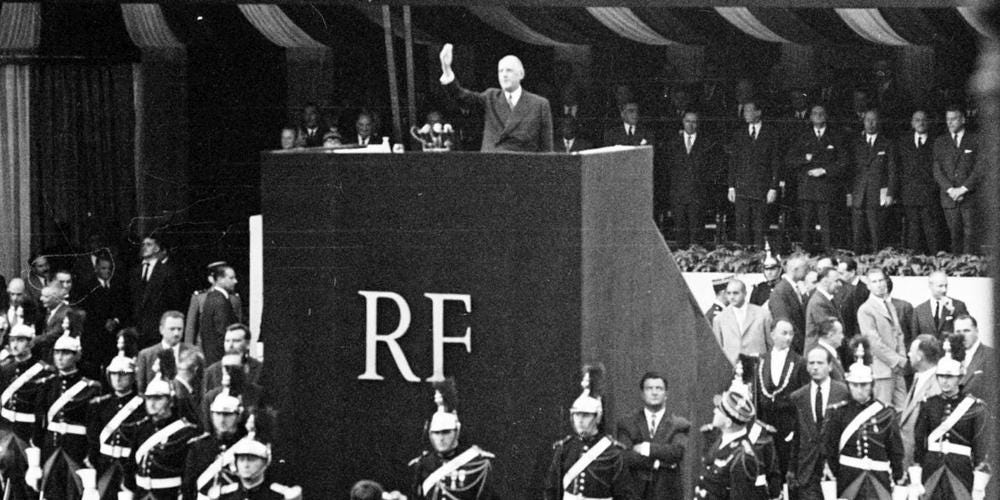

On September 12th, at the Council meeting following his return from Germany, the General begins by saying while looking at me: “Everything has been said and I have come too late…” Then he addresses the ministers. He speaks slowly, and, as usual, without notes.

“This about ensuring the longevity of the institutions. In 1958, I had these institutions approved by the people, by a majority like we had never seen in the history of the Republic. These institutions exist. We have put them in place. They have proven themselves. With them, we have gone through crises that would have toppled the previous Republics ten times over. We have accomplished a work of reorganization.”

“We have realized a complete change in our relationships with our colonies, which have become the best they could be. Abroad, we have acquired an influence, a prestige that we hadn't known for a long time. Our institutions are succeeding. Our duty is to maintain them. They were created, to a large extent, because of and by the one who speaks to you. It was natural: I represented and continue to represent a number of essential things, a moral capital that is intertwined with the nation.”

"It should not be that the disappearance of one man puts all of this at risk and throws the country into chaos, which would be instantaneous if we deviated from the institutions.”

“We have maintained the Parliament, which holds the legislative power. We have made adjustments so that it no longer controls the government. But it has the right to overthrow the government. Therefore, we have a parliamentary regime, as they say.”

“The government is coordinated by the Prime Minister, who has responsibilities that he is able to fulfill. He is enhanced by the new relationship that has been established with Parliament. Everything is possible, and will remain so, only if it emanates from the President of the Republic. It does not depend on variable majorities. It derives its source from the supreme authority. This is the key innovation of 1958.”

“We had suffered, under the two previous Republics, from the absence of such an institution. There was no one at the head of the State. The President's responsibilities are such that he must truly be the head of the State, the guarantor of the integrity of the territory, the independence of the Republic, the regular functioning of public powers, the head of the armed forces, the head of diplomacy with the power to negotiate and ratify treaties, and to enforce international texts. He has the right to dissolve the Assembly. And if everything falls apart, he can seize all powers… He has become a true head of State. This is a fundamental change compared to the Constitutions of 1875 and 1946.”

“If he could not maintain these prerogatives, we would return to the Third and Fourth Republics, that is, to the regime of parties, to the regime of assembly, which would correspond neither to the circumstances nor to public sentiment. Dramas would resurface as before. The presidential institution must be maintained after me.”

“I have thought a lot about this subject since 1958. It did not seem necessary, or even possible, to combine my election with the adoption of the principle of the presidential election by universal suffrage. Any electoral system would have resulted, in my case, in the same outcome. I held my legitimacy from History. However, a certain number of prejudices still existed against the Constitution itself and against the presidential function. It was necessary to accustom minds. Furthermore, universal suffrage would have meant, at that time, that there would have been almost as many overseas citizens as those from the mainland.”

“So we created an electoral college that went beyond the parliamentarians but remained a college of notables — in fact, the senatorial college. But my successor must be elected by the people and not by the parties, so as to dominate the parties and surpass them. Otherwise, he would become their plaything.”

“In order for the role of the President,” the General continues, “to remain what it is, for the institutions to continue to function, there must be a deep agreement between the President and the country. My successor will not have this agreement a priori. How could he have it, without being elected by the country? Therefore, the Constitution must be amended.”

“The French people are sovereign. Sovereignty comes from them. They hold it entirely. They can delegate it, but they possess it.”

“When a political choice can engage their destiny, it is fundamentally necessary that the country makes this choice itself. Their instinct pushes them to do so, and so does common sense. This is true in every respect, including legally. Any significant modification of the Constitution must come from the country itself.”

“The referendum has become part of our customs. I modestly admit that I introduced it myself. It was used to wipe the slate clean in 1945, then to reject a first Constitution, and finally to regrettably endorse the Constitution of 1946. In 1958, it was the people who adopted the new Constitution. It was legitimate. No other procedure could have been imagined.”

“Article 3 of the Constitution, which states that the people exercise their sovereignty through their representatives and through referendum, does not place any reservations on the use of the referendum. A parliamentary revision procedure is detailed in Article 89, as it is a parliamentary procedure and its modalities need to be specified. But for the referendum route, the Constitution is much less explicit, as it was much less necessary to explicate it.”

“The President of the Republic, according to Article 11, can submit any bill concerning the organization of public powers to a referendum. These terms refer to a notion as old as the Republic. The Constitution of 1875 (which founded the Third Republic, from which the Fourth and Fifth emerged) included a significant title: Law on the organization of public powers. This term cannot be contested.”

“To modify the electoral college, one might think it would have been better to wait until the seven-year term I accepted is over. But after what almost happened three weeks ago and could happen again, there would now be serious disadvantages to waiting. It has become essential to let the people decide, and to do so quickly.”

"It is not about changing the institutions, but about solidifying them. Each must retain their responsibilities: the President, the government, the Parliament, the Constitutional Council, the Economic and Social Council, etc. However, the balance of these institutions can only be preserved if the keystone remains in place. This is the only necessary change we need to make to the Constitution. We should modify it only to maintain it.”

“As for drafting the bill on this basis, it will be put under study. The government will finalize it in my presence. Then, the bill will be submitted to a referendum when Parliament is in session. It must be published at the very moment of the session's start. Parliament will have the power to overthrow the government by a vote of no confidence. This would not prevent the referendum and would only raise the question of the legislature's duration. If, on the contrary, Parliament accepts it, it will benefit from it.”

(In other words: ‘If the government is censured, not only do I not abandon the referendum, but I dissolve the Assembly.’ I remain momentarily stunned by the boldness, for if there is one thing the political world does not suspect, it is this.)

“You are politicians, even those of you who are not career politicians. You have political responsibilities to the French people. This may pose a problem for you. You may not necessarily be convinced by what I say. I would understand if you disagree and do not wish to assume the responsibility for such a significant change. It would be very understandable and perfectly legitimate. That is your concern. You have plenty of time to think about it. We will do nothing else at our next Cabinet meeting but address this issue.”

“I will not say anything to the country before the next Cabinet meeting. Until then, each of you can make your decision. I will not commit you until you have committed yourselves.”

After the Council meeting, the General discussed his plan with me.

AP: “Don't you find it strange, General, that most jurists, politicians, and commentators neglect the fundamental issue of the popular election of the President and focus only on the procedural issue — your preference for a referendum rather than a parliamentary procedure?”

CDG: “It's not strange at all! It’s understandable. It's difficult to explain to the sovereign people that they are neither worthy nor capable of choosing their principal delegate when they already choose their secondary delegates, the deputies. It is easier to suggest that the method we are going to follow would violate the Constitution. While the average citizen has the common sense and instinct to choose a President knowledgeably, they are not equipped to engage in legalistic arguments. Therefore, it’s the surest way to instill doubt in them. If I didn't address this point, I would expose myself to the most serious accusation — of dereliction of duty — since the President's primary duty is to respect and ensure respect for the Constitution.”

AP: “What worries me is that any crackpot could run. There were an average of seven candidates per constituency in the last legislative elections. There could be many more for the presidential election. Couldn't we ask the parliamentarians or at least the 60,000 notables who make up the current presidential college to do a preliminary selection? For example, only those who received 10% of the votes in this college could run for the popular election.”

CDG: “The smaller the electorate, the more it is susceptible to cabals and party directives. The larger the electorate, the more likely it is to escape the dictates of the party leaders. If you stir the contents of a bathtub with your hand, you create a storm, and the water overflows. If you do the same in a lake, it absorbs the disturbance and remains calm.”

AP: “But sorting out serious or frivolous candidates by the elected college wouldn't mean that the college would elect the President. The solemn act of the election would still belong to universal suffrage.”

CDG: “You cannot prevent a pre-selection from being a pre-judgment. It will act as a preliminary round. It would allow any faction to influence the elimination of the best candidate. We would fall back into the old system. Do not doubt that a restricted vote will always favor Deschanel over Clemenceau. Do not doubt that the notables will always choose the weakest, the most indecisive, the most inconsistent. And the ranking they establish might irreversibly influence the entire electorate. Let the people choose for themselves! Their instinct is surer than that of the parties!”

AP: “Don't you want to take advantage of this major reform to modify the Senate, as you mentioned to me once?”

CDG: “The Senate is an outdated institution in its current composition. It emanates from rural communes, which were the essence of France in the 19th century. Today, as it stands, it is just an assembly that only has legitimacy to deal with water supply systems. However, a Senate that absorbs the Economic and Social Council would acquire legitimacy to provide valuable advice on the entire economic and social life of the nation. But this is not the time. The next referendum must have one objective and one only: the method of electing the President; we must not overload the boat. This is for later.”

He straightens his head and becomes enthusiastic: “This will be the crucial turning point in the history of the Fifth Republic. We will break away from the system of notables, which had the effect of benefiting them with a multiplying coefficient. This reform aligns with the course of evolution! The notables are a relic. This method of election was not worthy of the presidential function as it was intended. We are going to put a stop to the long-standing push by the privileged to seize power, and thus the fate of the nation.”

With a mischievous look, hand on the door handle: “The French have been dispossessed of their sovereignty by Parliament. They will now be able to leapfrog over the abusive intermediaries, over the notables.” (He emphasizes this word.)

On the referendum establishing the President’s election by universal suffrage

Here comes the historic Council of Ministers meeting of September 19, 1962. The General summarizes “the two questions on which everyone must decide”:

“1) Is the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage necessary and sufficient for the keystone of the institutions to be maintained?”

“2) If we make this reform, should we do it by direct referendum of the people (that is, Article 11 of the Constitution), bypassing the parliamentary procedure (the one provided for in Article 89)?”

“I will give each of you the floor in a clockwise direction starting from the left of the Prime Minister, who will thus be able to conclude the series.” (He said ‘the series’: he does not consider himself part of it, unlike Pompidou.)

Each minister, in turn, speaks for three to ten minutes. They often repeat the same points, but the variations and even the reservations are significant. These are the aspects I will primarily recount.

Palewski opens fire: “The hostility of the parties towards your project proves that you're hitting the mark. If they had resigned themselves, it would have shown that they intended to regain control despite this reform. The opposition has been pounding the platform ever since the MRP withdrew, and now they feel cornered. You have taken the initiative back. If the Petit-Clamart assassination attempt had succeeded, we would have reverted to the Fourth Republic in less than six months, or six weeks. Now the regime must become unequivocally presidential.”

Foyer seconds the motion. He expresses his agreement with the substance. “But regarding the form, namely the direct referendum, through invoking Article 11, I have doubts about its conformity to the Constitution, since the procedure of Article 89, that is, the parliamentary route, is preceded by the title ‘On Revision’.”

CDG: “In legislative texts, titles and subtitles are not binding.”

Foyer: “I am well aware. But this title bothers me. Therefore, I suggest proposing for the referendum, according to Article 11, a bill inviting the government to submit to Parliament an amendment to the Constitution following the procedure of Article 89. In other words, ultimately through the Congress: it would be quite embarrassed, after this solemn consultation, to take a position contrary to that of the people.”

CDG: “But a referendum is not a Gallup poll! It would not be constitutional! Article 11 says: ‘The President may submit any bill concerning the organization of public powers.' This is the case!”

Foyer (refraining from retorting): “On the other hand, I advocate entrusting the interim not to the President of the Senate, but, as in the 1875 Constitution, to the entire Council of Ministers.”

Pisani: “The most important political act in the coming years will be the designation of your successor. Universal suffrage election is a timely modification. But we should choose between two conceptions: the parliamentary conception, where the President is an arbiter; the presidential conception, where the President is a leader.”

CDG (slightly ironic): “For the moment, the President has this dual function. Are you sure he doesn't have any others?”

Pisani: “Other questions. 1) Will the Prime Minister still justify his existence?”

(Pompidou makes a comical grimace.)

“2) The citizen cannot resist the influence of modern information means. We saw it in Kennedy's election. Hence the importance of an RTF status. 3) I have doubts about the two rounds. It would seem more appropriate to me that in the first round, only the current electoral body — the 60,000 elected officials — would intervene to make a selection of two candidates. Then, the second round would take place through universal suffrage and decide between these two candidates. Otherwise, we risk having a terrible mess in the first round.”

Triboulet adopts Foyer's reasoning, since Article 89 entrusts the revision solely to the parliamentary route, without mentioning direct referendum.

Boulin: “I also share the scruples of the Keeper of the Seals1.”

CDG: “If I understand correctly, the Keeper of the Seals has scruples, but he overcomes them.”

(Laughter from the usual flatterers, discreet smiles from a few others, or no smiles at all: the atmosphere is stern.)

The General believes it is time to clarify the question of the choice of Article 11. He approaches it more as a politician than a jurist:

“If we accept that Article 89 is the only means of amending the Constitution, we grant the Senate the incredible privilege of single-handedly blocking the Constitution. The President, with the support of the people, could amend the Constitution against the government and against the Assembly, vigorously bypassing these obstacles, since he can dismiss the government or dissolve the Assembly. But he could do nothing without the Senate, let alone against it!”

“We would thus create an almighty body. This is not possible! This is not what the drafters of 1958 intended! I am proud to be one of them. If we admit that it is not possible to act through Article 11, all reform becomes impossible due to the Senate.”

“Under the Third Republic, the Senate had political responsibility, but the President of the Republic had no substance. Now, demagoguery has turned towards the Senate. It can stop everything. It is an immovable assembly, without responsibility or sanction. It can say anything and wash its hands of it. It's no wonder it behaves irresponsibly. It is revealing itself to be, in its current form, a harmful relic.”

Gorse: “There are two problems. Your succession: it will not be resolved by a text. The presidential powers: the dimension of the function is created by your personhood, not by texts.”

CDG: “But also by the fact that the right of dissolution, the right of referendum, Article 16, etc., that is, texts, give the President new powers.”

Gorse (not forgetting his leftist origins): “You have enemies, and the RTF will not be enough to silence them. Your financial policy favors the business bourgeoisie too much, which is staunchly anti-Gaullist! I'm not sure this reform is useful. But I will be supportive.”

Marette: “The revision of the Algerian status was unconstitutional, as it undermined the integrity of the national territory. However, the left voted for it: they overcame their scruples.”

Sudreau's turn arrives. The atmosphere becomes tense. It has been whispered since yesterday that he is going to resign.

Sudreau: “This reform is dangerous. We must not overturn the fundamental law. You would create an unfortunate historical precedent. You would risk instituting an era of constitutional instability.”

“This reform is ill-timed. The end of the Algerian War has caused wounds. We must allow time for them to heal. You are and must remain the unifier. It would be an easy game for the opposition to say that you are dividing the French.”

His throat tightens.

“The Constitution must establish the balance of powers; you will be accused of creating an imbalance. I implore you to abandon this disastrous project.”

His voice breaks. Emotion grips the entire Council. The General makes no comment and gestures with his eyes to the next speaker.

Couve: “All the great Western democracies have moved towards a personalization of power, except Italy where, precisely, the parliamentary system functions very poorly. We must increasingly move towards a presidential regime. Legal arguments only mask political concerns.”

Malraux, in his cavernous voice, speaks as the Pythia must have done on her tripod:

“Will this reform be sufficient? Certainly not. Nothing is ever sufficient. Otherwise, history, since time immemorial, would have had different colors. Answer to your two questions: Should your successor be elected by universal suffrage? Yes. How could it be otherwise? You yourself were elected invisibly (sic) by the universal suffrage of the French. Will this reform be voted on by referendum? Yes. How could it be otherwise?”

“My colleagues have been concerned about your succession in the event of your disappearance. But there is another case, which is more probable and desirable, that of your retirement and not your disappearance. If the President of the Republic steps aside without disappearing, what will happen? It is not possible to fall back into the system of notables, for there are no longer notables in the age of jet planes, satellites, and television.”

“Clemenceau, Painlevé, and Briand were ousted from the Élysée by the notables. Yet each of them could have saved the Republic. Your successor must be able to save the Republic.”

AP: “We are in a hybrid system, part presidential, part parliamentary. Shouldn't we just say it outright and delete Article 20, which states that the government, accountable to the Assembly, ‘conducts the nation's policy’? This article maintains ambiguity and becomes anachronistic.”

The General charges at me with a lightning strike:

CDG: “The American-style presidential system is not a system for France. And we shouldn't always fear ambiguity. It can have advantages.”

AP: “As for the procedure, why not make the government accountable for this constitutional reform? We would have given priority to parliamentary maneuvering. If the opposition votes for censure, they will have initiated the aggression; we will have a good chance of winning the referendum and the subsequent elections.”

CDG (annoyed): “That’s a tactical matter We'll see. For now, we're focusing on setting the strategy.” (Laughs.)

Missoffe (under his breath): “You're being put back in your place.”

Broglie: “Just as one judges a writer by his second book, one judges a regime by its second term. The future of the country and the Republic depends on how the next Assembly is elected. If it is composed of an anti-Gaullist majority, all the laws passed under your leadership will be gathered, and there will be a massive auto-da-fé. To build on solid ground, we must ensure the re-election of friends and the elimination of adversaries.”

“No one has spoken about the President of the Republic's power of interpretation of the Constitution. It is a fundamental power, explicitly recognized in the Constitution. It is precisely in cases where jurists are divided that the President of the Republic must use this power. He has the means to do so by appealing to the sovereign people, following the right expressly granted to him. He observes the discussions among jurists. He gives his opinion, and the people decide.”

Fouchet: “I won't indulge in the game of victory at Waterloo, nor in what would have happened if Lebrun had been elected by universal suffrage and had your powers. What seems plausible to me is that Lebrun would never have been elected by universal suffrage.”

Joxe (as if he hadn't heard the General's retort to me): “I am in favor of election by universal suffrage because I am in favor of the presidential system, towards which we must increasingly move. But one day, we will have to modify the Constitution, taking into account the imbalance introduced by this reform. Seven years is too long. The term should be reduced to five years and made to coincide with the legislature. This way, we would ensure agreement between the President and the Assembly.”

“Finally, the President of the Republic's power of dissolution should be abolished.”

Pompidou, last to opine, interjects: “What would be the domain of Article 11 if it did not apply to the revision of the Constitution, and if the parliamentary procedure, that of Article 89, were the only way to revise it? It could not apply to ordinary laws or organic laws, which are covered by other articles. It would therefore apply to nothing at all. Since the war, all constitutional texts have been adopted by referendum — both in 1946 and in 1958. Why couldn't it be so for this new text?”

The General concludes, without individually responding to anyone:

“Herriot had accepted to be president of the National Assembly of the Fourth Republic, although he had refused to admit that the Third Republic be abolished. He invoked the shadow of Bonapartism. He pursued it in General de Gaulle. It is already the weight of this precedent that crushed the Third Republic. Gambetta, Jules Ferry were eliminated by the Senate because it feared the emergence of a strong man.”

“The parliamentarians would like to regain the fullness of their powers, by recovering the ability to designate the President of the Republic. The State was a body without a head. It would inevitably become so again. Poincaré, in ‘Au service de la France’, explains how, in fourteen months, three governments were reduced to impotence. Lebrun, in 1940, was forced to step aside for Pétain. Coty, in his message to Parliament in May 1958, showed that the 1946 Constitution confined the President to the inability to play his role.”

“The Constitution will undergo an evolution. It is a text that is too long, too complicated. One must always walk straight towards the truth. And the truth is national sovereignty.”

“So, here's what we're going to do.”

“We will prepare a draft law that will be submitted to a referendum. Perhaps we will modify the conditions of the interim? Maybe we should exclude jokers like Ferdinand Lop? Do we need fifty signatures, a hundred? That remains open.”

“For the second round, we need two candidates, so that one of them wins with the majority. We are not yet very clear on this point. I recognize that the provisions provided are not very satisfactory. (A pause.) For the most part, the matter is settled.”

After a moment of silence, he addresses Pompidou: “So, Mr. Prime Minister, in accordance with Article 11 of the Constitution, you propose to me, on behalf of the government, to submit to a referendum a bill aiming to modify the conditions of the President of the Republic's election.”

General laughter erupts. It takes a de Gaulle to pretend to believe that his ministers propose to him what he imposes on them.

He did not respond to the dramatic call made to him by Sudreau. But he resumes, turning to Sudreau after lightening the atmosphere with a deadpan expression: “I will personally receive anyone who still has doubts, which would seem quite natural to me.”

[…]

Pompidou, unperturbed, cheerfully repeats the joke he made after the resignation of the five MRP ministers: “All this is going to end with a homogeneous Bonneval government.”

In private, he did not hide from me, although he presented convincing arguments in the Council to justify the use of Article 11: “What we are going to do is on the borderline of legality. I even believe that we have crossed that line. Anyway, if we win, the limit will be pushed back. We can say, paraphrasing the famous phrase: ‘It's legal because the people want it!’ But the General always wants to raise the bar even higher. One day he will break his neck, and we with him.”

In reality, we are in the midst of a perfect storm. Alarming rumors are circulating. Monnerville, the Radicals, the Freemasons have sworn to finally bring down the General this time. All the political formations that had supported the government — or at least had not fought it — until the Évian Accords will now unite against him: “Let de Gaulle rid us of Algeria,” Maurice Faure had prophesied, “then Algeria will rid us of de Gaulle.”

The moment seems right to them. In the meantime, the Constitutional Council, the Council of State, and the legal and moral authorities have overwhelmingly pronounced themselves, not against the project, but against the referendum procedure — which alone, obviously, can open the door that, with jubilation, the Assembly and the Senate are preparing to bolt shut.

The censure, it is repeated in the corridors, will be voted with an overwhelming majority. Assuredly, it will bury the referendum. After the elections, which will happen promptly, a strong Fourth Republic majority will be installed in the Palais-Bourbon. De Gaulle will have nothing left to do but leave. Monnerville will act as interim president and will be easily elected by the college of notables. One uncertainty remains among so many assertive statements: “Wouldn't it be better for Monnerville to step aside for Pinay?”

[…]

Élysée, September 26, 1962.

As the General had warned us, each of the twenty-five ministers and secretaries of state will once again have to express their opinion in the Council. Around the Council table, as we arrive, two texts await us on each blotter: one outlining the modalities for the election of the President of the Republic, the other setting forth the limitations that would be imposed on the exercise of interim powers by the President of the Senate.

CDG: “1) What precautions will be taken to ensure that only worthy candidates can run, and that the shysters are excluded?”

“2) Will there be a second round, and do you approve that only the top two candidates from the first round can run in the second round?”

“3) Regarding the interim, do you agree with the proposed formula, namely that the President of the Senate continues to assume it, but without the power to change the government or amend the Constitution? Or would you prefer that the interim be exercised by the government, as in the 1875 Constitution?”

“Gentlemen Ministers, please respond to each of these three points in reverse order from last time (that is, counterclockwise starting from the Prime Minister). Mr. Minister of State, it's your turn.”

Joxe: “The requirement of 100 sponsors seems very insufficient to me. And I am not favorable to a change for the interim; it would appear, in relation to Mr. Monnerville, an unnecessary and dangerous suspicion.”

Fouchet: “This text seems excellent to me. It answers all the questions that can be raised. I agree from beginning to end and I really don't see what could be changed.”

Broglie: “As an old Jacobin that I am by family tradition (laughter), I worry about the Girondin ferment contained in this project. If we allow 100 elected officials to submit a candidacy, we encourage local autonomy. 100 mayors from Brittany, Alsace, or Corsica will quickly present their candidate. This is, in essence, the fragmentation of France! I demand that these 100, if we must stick to this number, be recruited from a minimum number of departments, let's say 10.”

(This suggestion is warmly approved by the UNR ministers, who had agreed two days earlier to present it unanimously, and are vexed to see that they have been outmaneuvered.)

AP: “1) The interim President will oversee the electoral climate. However, I have no confidence in the current formula or in the 1875 formula, which entrusts the interim to the entire government. Whenever in France there has been an attempt to establish a collegiate government, under the Regency, under the Directory, it has gone wrong. The interim of the President should be ensured not by a college, but by the Prime Minister.”

CDG: “I am not far from thinking like you. But it would not be necessary to include these provisions in the Constitution itself. It would suffice for it to be a text internal to the government.”

Foyer intervenes out of turn, for clarification: “This text already exists. An ordinance from 1959 provides that in case of impediment, the responsibilities of Commander-in-Chief pass from the President to the Prime Minister, then to the ministers according to the order of precedence.”

AP: “2) I'm not afraid of a Ferdinand Lop, but rather of a General Boulanger, a Pierre Poujade, or a Thorez: a popular tribune capable of stirring up the masses, but not of leading a country. In ancient Rome during the Republic, a cursus honorum was imposed. To be consul, one had to have been a quaestor, tribune, censor, praetor, aedile. Could we not transpose this, allowing only men who have proven themselves by playing a prominent role in the service of the State to run? For example, former Prime Ministers, former Presidents of the Assemblies or the Constitutional Council. That would already offer a wide choice.”

CDG (mockingly): “But we should also add ministers, parliamentarians, ambassadors, councilors of State, and even university professors.”

(As last week, he makes the Council laugh at my expense; bursts of genuine merriment.)

Marcellin: “100 mayors are quite enough. And we wouldn't find 100 autonomist Breton mayors. It's not that easy to have 100 mayors on your side. But on the condition that they commit personally and publicly take responsibility for the candidacy they present. They shouldn't be ashamed sponsors.”

Most of the other ministers, from the UNR, agree to the reform, on the condition that sponsors come from at least ten departments; they prefer that the interim be entrusted to the government.

Prey: “Regarding the interim, as I am personally attached to republican traditions, I wish to return to the 1875 formula.”

(This republican profession of faith by Prey is greeted with laughter by Pompidou.)

“If it is found that this modification would be offensive to Mr. Monnerville, it must be observed that the current provisions are no less offensive to Mr. Chaban-Delmas.”

(The barons close ranks.)

Jacquinot: “If we change the provisions concerning Monnerville, we would seem afraid of him.”

This truism did not seem worth noting, but when Malraux intervenes, it is always in reaction to what has just been said immediately before him. His mind is so quick that if it's his turn to speak, he is unable to hold back a reply to a colleague's intervention for long. A few minutes later, he would have already forgotten his reaction, to react to new information.

Malraux: “Whether Monnerville or not, it’s all the same to me. Every time a decision has been made based on a person, the consequences have not waited too long to come out. We must decide without worrying about who is currently President of the Senate, and history will thank us for it.”

Everyone listens intently to Couve, a potential successor, when he speaks up: “100 sponsors are quite enough! One might even wonder if it's not too many. And what advantage this gives to rural mayors!”

(Missoffe, at the end of the table, quips: “Couve is afraid he won't find 100 elected officials to sponsor his candidacy.”)

“You said: ‘We must replace a complicated system, that of notables, with a simple operation, that of universal suffrage.’ But you are complicating the adoption of this constitutional reform with provisions that weigh it down. Let's stick to the reform planned last week!”

(Pompidou, seemingly the target of these words, taps on the green carpet, a sign of impatience for him.)

Tension returns to the atmosphere when Sudreau speaks up.

Sudreau: “To answer the questions posed first, I would like us not to twist the texts. Anticipating that the interim presidency exercised by the President of the Senate will no longer be, or will simply be subject to all sorts of restrictions, it smells so much like a desire to pettily revisit the current provisions of the Constitution that I fear the regime may not emerge from this unscathed. I request that in any case, we stick to the previous text.”

“But I take this opportunity to remind you how ill-timed I find the initiative you have taken, General. I ask you to abandon the referendum approach. I repeat that I am in favor of the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage. But why not proceed with the normal method, which would raise no criticism from anyone: the method of constitutional revision through Parliament, all the details of which are provided for in the Constitution.”

“I understand well, General, that you wish to act quickly, fearing that misfortune may befall you before this reform is accomplished. But if ever this misfortune were to occur, why don't we all here make the oath to continue the work you would have started and to bring this reform to fruition before the assemblies?”

(Here, Sudreau's throat tightens, as it did last week; the Council is gripped by emotion.)

“General, you are, for all of us, the embodiment of legitimacy. You cannot become a symbol of illegality. I beg you to abandon your project. You would enhance your stature by renouncing it, by showing yourself scrupulously respectful of the Constitution, which must be placed above us all.”

CDG (with an ice cold tone): “I thank you, Mister the Minister of National Education.”

Marette: “To dismiss whimsical or dangerous candidacies, I believe a minimum of 1,000 sponsors is indispensable; 2,000 or even 5,000 would be even better.”

Pompidou enthusiastically agrees, albeit quietly, as if he didn't want to irritate the General by revisiting a point where he knows the General has a strong stance: “We absolutely must block whimsical candidates, and even conduct a severe selection, otherwise it will be chaos.”

Gorse: “1) I am not in favor of the two-round system, which is tricky and dangerous. Between rounds, who knows what deals could be made behind the scenes. I would prefer to adopt the Australian system, also the Irish system, meaning a single round but with preferential voting.”

(The General, who clearly has no idea about such a system, asks Gorse to explain.)

“It involves ranking the candidates: you put a ‘1’ next to your preferred candidate, then ‘2’, ‘3’, ‘4’, etc. Then electronically, the total is calculated. One round suffices, eliminating maneuvers, withdrawals, and blackmail.”

CDG: “Your system is excellent, but it assumes all voters are polytechnicians2.”

Gorse: “2) I would gladly support the abolition of the Senate. However, if it remains, it's not dignified to play with marked cards.”

CDG: “I draw your attention, everyone, to the fact that we are not aiming for a vast constitutional reform, but simply a touch-up to allow the Constitution to remain itself; otherwise, it will not withstand. It's possible that in the future, significant modifications to the Constitution may seem desirable. All of this remains open. We will proceed with it later, if we have the time. The Third and Fourth Republics could not or did not know how to amend their Constitution; the Fifth Republic can. But today, that's not the question. The Constitution will evolve in the future all the better because this time we will have shown the way to an amendment through a referendum for a specific and limited objective. We will have shown that it is not immutable. A Constitution, as Solon said, is good for a people and for a time. It must not be mummified.”

Dumas: “I am concerned about the provision that only the top two from the first round can proceed to the second. We risk having a left-wing candidate and a right-wing one. The left-wing one opens the door to the Popular Front; the right-wing bloc against the communist danger. Between the two, we risk not having the centrist candidate who, however, would be best placed to arbitrate and exercise reasonable power in the future.”

Triboulet: “I fear that we will be overwhelmed by a quantity of local or whimsical candidacies, which would discredit the presidential election. Anyone can recruit 100 sponsors.”

CDG: “But why can't all these local figures run? Why do you want to prevent them? Why are you afraid of folklore? Isn't democracy precisely about everyone being able to run for election? The people will sort it out! They do it well for legislative elections. They will do so all the more at the national level!”

Triboulet: “The two candidates in the second round risk being the two extremes. It seems to me essential in this matter not to move away from the MRP, which will play an important bridging role. However, it is haunted by the fear that the country will be divided in two.”

CDG: “Do you believe it prefers that we divide the country into three?”

After a pause, he continues: “Why don't you trust the people? I am convinced that automatically, from the beginning of the campaign, there will be an instinctive concentration! I cannot believe that the country, as a whole, will not be guided, when the time comes, by a sort of instinct. It will elect someone who is not an extremist.”

(Impressive, this confidence of the General in the wisdom of the united people.)

Triboulet (who is never intimidated by the General): “But I repeat, the MRP will be against it.”

CDG: “Unless they hope to benefit from it.”

Foyer (again out of turn, for a joke): “I don't see why the MRP would be hostile to this provision. It is taken from canon law for the election of superiors of congregations. How could we please the MRP more than by copying canonical provisions?”

(General laughter.)

Triboulet: “For the second round, I would prefer that we provide that only those who have at least 10% of the votes can run. Two million votes are already enough to eliminate a good number of troublemakers.”

CDG: “This provision cannot be retained. The purpose of the presidential election by universal suffrage is to place at the head of the state someone elected by the majority of citizens. Otherwise, the character of the presidential function would not be respected. The President would be of a minority. He could not perform his duties.”

Triboulet: “I cannot agree with Mr. Couve de Murville's conclusions. The Minister of Foreign Affairs views the issue of elections as a diplomat calmly watching storms from the peaceful shore where he himself resides.”

The General reacts to defend Couve as vigorously as if he had been personally attacked: “The shores where the Minister of Foreign Affairs stands are not always as tranquil as you say.”

Then, as if wanting to reposition himself in an arbitration role by partially agreeing with Triboulet: “It is true that, in this particular case, he is exempt from the election trial!”

Triboulet: “The Minister of Foreign Affairs does not realize that the elite is fiercely hostile to us.”

CDG: “The elite? You mean: those who present themselves as elite.”

Pisani: “1) While being in favor of the election by universal suffrage, I do not agree with the interpretation given (that is to say, what you have just given us). I do not believe it is merely a confirmation of the Constitution, but indeed a fundamental reform.”

“2) The communist threat is a serious danger. It is possible that the communist will be first in the first round. In any case, it is the candidate best placed from the point of view of anticommunism who will be ahead either after him or perhaps before him; he will have been chosen not based on his ability to lead the country, but based on his anticommunism. Here is a very unfortunate division: communists on one side, anticommunists on the other! These provisions do not allow for the political organization of France around the two tendencies that would be most necessary for the future of the country: center-right and center-left.”

“3) It seems formidable to cast aspersions on elected officials or elites. We do not have the right to overturn our elected officials: it would be a way to question universal suffrage! And the elites, the opinion leaders, I don't see how a society could do without them.”

“4) There is nothing easier than being pushed forward by 100 rural mayors.”

(At the end of the table, Maziol, in a low voice: “If it were that easy, Pisani wouldn't have lost in the local elections!”)

“We should go up to at least 1000, to avoid scattering that would put the communist candidate in a privileged position. In this regard, this text does not ease my concerns. Nor in other respects.”

Giscard, sitting upright in his chair, looking directly into the General's eyes, speaks with his usual authority and eloquence: “Having not attended last week's debate, I will not merely answer today's three questions, but if you allow me, I will present my overall position.”

“Should the President of the Republic receive the consecration of universal suffrage? Yes, without a doubt.”

“But what is the risk of this operation? It is that universal suffrage might result in an unfortunate choice, in which case it would be a failure. There are many examples of national collapse following an unfortunate choice: Brazil, Argentina, and others!”

“The fundamental phenomenon of French politics from 1936 to 1958 was instability, incessant fluctuations. This phenomenon is masked by the person of the current President of the Republic. Nevertheless, since 1936, no personality has had sufficient authority in the face of universal suffrage to emerge as a dominant figure.”

“We risk having six to eight serious candidates in the first round; in the second round, it is not excluded that among the two leading candidates, we might have a prominent communist and a national candidate, diminished by the scattering of votes among all national candidates. The election would then be presented in very poor conditions.”

“I believe, therefore, that the notion of pre-selection is crucial.”

“I add that the timelines will not allow for a proper campaign. In the United States, the campaign actually lasts a year, and for three months, it intensifies to the point where no one thinks of anything else. It seems essential to leave at least fifteen days between the first and second rounds, if only to allow the candidates physically to conduct their Tour de France. I even wonder if that's enough; a month, maybe even six weeks, seems more reasonable to me.”

Pompidou cuts in somewhat sharply: “If we were in an interim period, it would be dangerous to spread a campaign over two months; no one can predict what the interim will bring.”

Giscard resumes, addressing the General by name as if to show Pompidou that his remarks were not directed at him and that he did not appreciate his intervention: “General, if we're talking about a historical figure like yourself, it's obviously not necessary for them to present themselves at length to the French. But if, as will likely be the case in the future, we're talking about a figure whom history hasn't revealed yet, the election campaign will be the determining factor.”

CDG: “One should not confuse a historical figure with an electoral figure.”

(It slipped out naturally. The General is obviously referring to himself. Indeed, he has never been elected by universal suffrage, not even as a municipal councillor. His essence is not electoral but historical. The form of his observation is modest, even if the substance is not.)

Giscard: “Regarding the interim, it does not seem appropriate to me to mix provisions concerning the interim with provisions concerning the election modalities of the President of the Republic. However, if we address the issue of the interim, it is reasonable to suspend any constitutional revision.”

CDG: “I fail to see how increasing the number of sponsors to 1000 or 2000 would allow for better pre-selection.”

Giscard: “I would propose an even more selective system. I would like only those who have obtained 15% of the votes from the current restricted college of notables to be able to stand in the first round of the universal suffrage ballot. This procedure would encourage candidates to campaign among the pre-selectors. The difficulty of this initial campaign would discourage eccentric candidates. It would keep out figures like Ferdinand Lop. We might then have, in total, a socialist, a PSU member, a communist, one or two radicals, one MRP member, one UNR member, and two independents. That would already be a significant simplification.”

CDG: “Your system is a continuation of restricted suffrage.”

Giscard: “On the contrary, it's a means to rid universal suffrage of impurities that could suffocate it. What would prevent, for instance, the 800,000 repatriates from presenting their candidate?”

CDG: “But the repatriates don't count! First of all, they won't be 800,000 voters, but at most 300,000! And besides, universal suffrage simplifies things. It won't take into account all these subordinate measures you're considering. It will be a basic and fundamental movement. But you can't simultaneously elect the President of the Republic by universal suffrage and restricted suffrage. A choice must be made. I have made mine.” (implying: if anyone around the table disagrees, I won't hold them back)

Never before, since the Pompidou government took office, had a Council lasted so long. Yet the General shows no impatience.

Foyer: “1) I find it inappropriate that members of the Economic and Social Council are authorized to act as sponsors. It is not a political assembly. By involving it in a political election, we would divert it from its purpose.”

CDG: “I agree that members of the Economic and Social Council are neither elected nor politicians. But first of all, they are individuals of unquestionable quality. And they have a constitutional role: the Constitution precisely defines the extent of their powers, which are not negligible. So, why exclude them?”

“Finally, understand that the Economic and Social Council is in line with history. An evolution is emerging that will give its members and all the forces they represent increasing importance.”

A brief silence follows this statement. Obviously, the General has in mind the future Senate, which is already taking shape in his mind with representatives of the “vital forces of the Nation.”

Foyer: “2) This text is too complicated. We could later specify the details by ordinance or by law. We should stick to a brief and simple text that simply lays down the general principles on which the referendum is based.”

“3) However, I believe it would be more reasonable to allow everyone in the second round, including newcomers. The weeding out will happen naturally, and the people will find their way.”

“4) The provisions for the interim are clearly aimed at the President of the Senate. Should we be so scrupulous in this regard? It is not, for the current President, a vested right, but a mere expectation, null in terms of future successions, as I teach my students (laughter).”

Almost all our opinions are marked by a certain mistrust of universal suffrage, or by tactical considerations linked to the current electoral landscape. De Gaulle, on the other hand, sees salvation only in the people. He wants to create a situation that can endure beyond present circumstances. He projects himself beyond the horizon of our imagination.

[…]

Council of October 2, 1962

This text, heavy with consequences — even though the General tries to minimize them, each of us feels them well — comes before us for the third and final time.

CDG: “Does anyone have any final observations regarding the referendum bill that is to be published tomorrow morning in the Official Journal?”

Broglie: “Could we not take this opportunity to introduce an essential reform in France, given our unfortunate tendency towards abstention: compulsory voting?”

CDG: “That is a serious subject. This reform should not be excluded at all. There is nothing to prevent, in the future, when drafting an electoral law, from providing for compulsory voting, both for the presidential election, the parliamentary elections, or a referendum. But I do not think it is necessary to raise a new issue in a bill that is already very substantial.”

Giscard: “Why put in the preamble to the bill: ‘The French people, exercising its constituent power’? If we want to refer to Article 11, let’s do so. But what is the point of declaring a general principle about the constituent power that the people would hold? Isn’t this giving our critics ammunition to use against us?”

CDG (turning to Giscard): “I agree with you. There is no need to hide behind our little finger. I do not see why the recourse we are making to Article 11 would not dare to say its name. We must take the bull by the horns, as always on great occasions. It is indeed Article 11 that we are using.”

Pompidou (grimacing while Giscard was speaking): “I had put the phrase ‘exercising its constituent power’ in order to avoid a debate about whether it was Article 11 or something else. But I recognize that this assertion of principle was somewhat provocative.”

The General has accepted Giscard's suggestion because he wants to be provocative; and Pompidou, because he wants to avoid being so.

CDG (addressing Pompidou): “Why did you go from 100 to 200 sponsors? That's too many! 100 are quite sufficient! Either the elected officials give a real endorsement, and then we need to go all out, as the Minister of Agriculture wished, by conducting a proper preliminary election by a restricted college. Or we abandon this system, adopt universal suffrage in its full extent, and then there should be no prerequisite condition.”

Pompidou notes that Coste-Floret recommends 150 sponsors. So, if we want to win over the MRP… (laughter).

CDG (not disputing the value of such a reconciliation): “Coste-Floret wanted to split the difference. Let’s split it too. Let's go for 150!”

But, as this remark makes people laugh, the General withdraws his compromise proposal and concludes: “Come on! Let’s say 100. It’s still less convoluted.”

No one dares to challenge the General’s verdict anymore. However, a strong majority of ministers were asking for at least 500 or 1,000. Couve was completely isolated in finding that 100 was already too many (it is true that he was already isolated in 1958 by declaring himself in favor of Algerian independence — and history has proven him right).

CDG: “We still need to set the date for the referendum.”

Pompidou: “It is in our best interest to proceed as quickly as possible. Minimum time frame: Sunday, October 28.”

Grandval: “If the censure vote passes, wouldn’t it be advantageous for the elections and the referendum to take place on the same day?”

(The ministers, like Grandval, have absorbed the General's discreet warning: the censure will immediately trigger dissolution. This is not suspected outside this room.)

CDG: “We’ll see. In that case, what our decree today has done, another decree can undo. If necessary, we could align the two dates.”

Pompidou impartially outlines the reasons for and against staggering the dates.

Pompidou: “Advantages: The first round would benefit from the shock effect produced by the referendum results (if they are favorable!). We would then observe a gain between the referendum and the first round — as between the first round and the second round of the 1958 legislative elections in favor of the UNR. The wave cannot swell if the first round is coupled with the referendum.”

“Disadvantages: Those who voted yes for de Gaulle in the referendum will not feel the need to do so again a week later. Believing they have supported de Gaulle himself in the referendum, they will refuse to commit to his soldiers the following week; or they will have voted for de Gaulle reluctantly, fearing he might leave, but will vent their frustrations in the elections. Conversely, if everything is done on the same day, it is not possible to put a yes ballot in one box and a ballot for the one who says no in the other.”

Pompidou concludes, however, that it would be better for the referendum and election dates not to coincide, and that voting should take place over three consecutive Sundays: referendum, first round, second round. After discussion, the General ultimately decides to further separate the two processes: the legislative campaign will only begin after the referendum.

I raise the issue of repatriates, who are excluded from the vote due to the six-month residency requirement. I request that they be granted the same status as military personnel, who can vote wherever they are located.

“They are going to vote massively against us, but it would be surprising if the result hinges on a few hundred thousand votes. And it would be an elegant, or simply fair, gesture that would help integrate them into the national community after the trauma they have just experienced.”

Joxe raises difficulties: “A certain number of repatriates do not want to be known, as they have things to hide. There are many repatriates who are ashamed, who blend in with the OAS.”

AP: “All the more reason. Those people will not seek to register.”

The General remains silent. I was sure that once the words “fairness” and “elegance” were mentioned, he would not show any hostility. No one says a word.

He concludes soberly: “The right to vote is granted to the repatriates, or more precisely, to those among them who have registered with the services of the Minister of Repatriates.”

(He never says ministry: a ministry does not have its own existence; only the responsible person counts, who, in this case, is supposed to handle the registrations himself.)

Now it remains to determine the modalities of television propaganda for the referendum. It is planned that all parties represented in Parliament will be able to participate in the campaign.

Frey: “A new group is soon to be created in the National Assembly, including former members of the Unity of the Republic (‘French Algeria’) and a few other parliamentarians of the same ilk. If we are not careful, they will be able to participate in the propaganda.”

CDG: “Why doesn't the UNR split into three? That way, it would be entitled to three speakers on television! Then we would be sure to win the game!”

Laughter. It is decided that only parties represented in Parliament as of the date of the decree can participate in the campaign.

Grandval asks for clarification: “represented in Parliament or in the government.”

General laughter. De Gaulle joins in the hilarity and does not follow up; Grandval's proposed addition can only concern the “left-wing Gaullists,” who are present in his person in the government but were unable to get a single candidate elected in 1958, as if France wanted the Gaullists on the condition that they were not “left-wing.”

As the Council ends, Grandval approaches the General: “So, my general, you did not grant us the right to speak! What a shame! I wasn't asking for myself, but for Vallon. I always think of him. He is your most valuable supporter. When they wanted to appoint me Minister of Labor while I was only Secretary of State for Foreign Trade, I said: ‘No, it's Vallon who should be appointed.’ But they never think of Vallon. Yet he is the best.”

On the spirit of the Constitution of 1958

After the Council on April 30, 1963, I tell the General that there's a lot of talk about changing the Constitution, adopting a fully presidential regime, or transforming the seven-year term into a five-year term.

CDG: “That proves people still haven't understood the spirit of this Constitution.”

“If we switch to a presidential regime, the Assembly would lose its last power, that of censuring the government or threatening to do so, and the President would lose the power to dissolve it. The President and the Assembly would have no control over each other. It would lead to a deadlock — opening the door to paralysis or a coup d'état. The people must be able to decide. As for the American system… Can you imagine if nominations of prefects had to be approved by deputies…”

AP: “And the five-year term?”

CDG: “It would make the presidential mandate more precarious.”

“The risk, if the presidential election coincides with the legislative election, is that the President would become a prisoner of the Assembly, meaning the parties. Both consultations, in quick succession, would result from electoral deals. However, everything in this Constitution has been arranged to allow the President to escape these deals and to put the government in a strong position vis-à-vis the Assembly. There isn't necessarily a perfect agreement between the majority that elected the President and the legislative majority. But the President must be able to manage as long as he isn't disavowed by the people.”

“If the Gaullists accept the presidential regime, they would themselves dismantle the Constitution they wanted. Think about that for the future.”

[…]

At the Council on July 31, 1963, Pierre Dumas presents the summary of the parliamentary session that is ending, productive but marked by nervousness: “As soon as there is pressure from the opposition, all the deputies of the majority come together. However, today's majority has integrated the fact that the regime is well established. So, it has some mood swings.”

Pompidou: “I ask the ministers to spend more time in the Assembly. Many of them think that the majority should just march to the cannon. Appearances must be maintained. Conversely, if we push too far, we fall back into the regime of the Assembly; and I have sensed at the Palais-Bourbon a tendency to consider that the majority has rights over the government.”

CDG: “As long as there is a Parliament, one cannot prevent tendencies from manifesting there. No matter how cordially adherent the majority is as a whole, they are men, they are rivals. One cannot prevent the temptation of quarrels and plots. Some do not understand why they are not ministers; they do not forgive those who are. Others have their obsessions. The vanity fair is somewhat inevitable. And then, they have the idea, as soon as they are elected and the ushers bow, that power proceeds from them.”

“But (the tone stiffens) the Constitution is made to prevent these temptations from resulting in public authorities being unable to fulfill their mission. That is the whole issue. If the majority deputies do not accept it, they cease to be with the government, with the head of state, with the Constitution they have approved. They are there by virtue of an immense movement that has swept across the country and created this Constitution, this regime, and many other things.”

“The government must not yield. It must not be at the Parliament's beck and call, not even of its majority in Parliament.”

"At the end of the previous regime, ministers were perpetually summoned by groups, commissions, etc. We must obviously avoid that. Ministers do not belong to their party. But it is good that, on your own initiative, you maintain cordial relations with parliamentarians, or at least with those who are not unconditional opponents — because there is only one category of unconditionals in French political life, and that is unconditional opponents."

[…]

Salon doré, on September 25, 1963

I asked him: “Do you plan to organize a referendum by the end of the year?”

CDG: “Certainly not. Maybe in 1964. But more likely in 1965.”

AP: “In that case, would this referendum serve as a locomotive for the presidential election?”

CDG (with a smile): “Yes, perhaps, for example.”

In his mind, this referendum would complete the constitutional edifice. The centerpiece would be the replacement of the Senate with a Council, already outlined in 1947 in the Bayeux speech: a consultative assembly that would include both the former Economic and Social Council and the elected representatives of the new regions, whose organization is beginning to take shape. But this is not the only problem that the referendum could solve through the people.

AP: “In 1962, you considered revising the relationship between the President and the government. Is this still part of your plans?”

CDG: “Yes, and this reform must go hand in hand with the reform of the Senate. The President has extraordinary powers. He is the guarantor of national independence. In the event of a great national emergency, he is a Roman-style dictator. As for the rest, even in ordinary times, his power is permanent: he provides direction and impetus. The Prime Minister must be placed under his direct dependency.”

“When it is about me on one hand, and Debré or Pompidou on the other, there is no problem: they will not try to evade. But, with my successor, the problem may arise. In the current state of the texts, the Prime Minister can oppose the President of the Republic by refusing to resign if the President wants to end his functions. This is not normal, logical, or in line with the spirit of the Constitution and the interest of the country. The government can only be the emanation of the President of the Republic; otherwise, there will be a contradiction between them. The State must not be overshadowed by a two-headed eagle.”