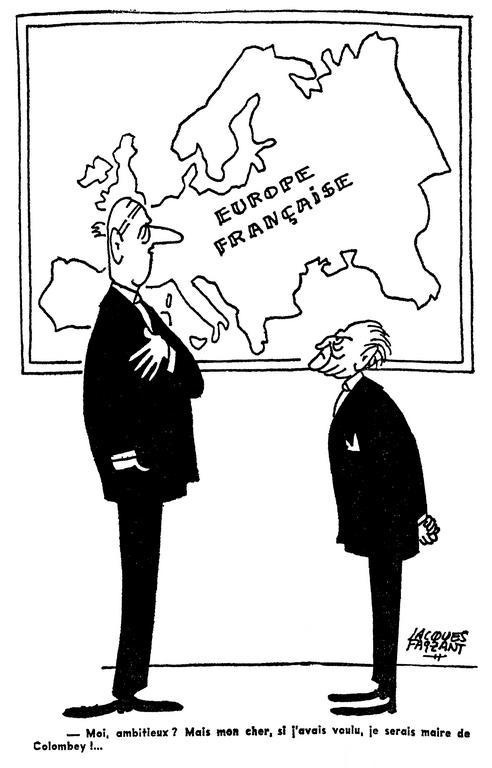

This time we take a look at some of the General’s opinions on the European project, all the way from the very beginning, to the European Communities, the Europe of the Six, and his far reaching outlook to the technocratic European Union that we have today.

Throughout all this, you will see a common thread: de Gaulle believed that there was no Europe without its nations, without restoring the German nation, and chiefly, without France.

Before we begin, I must welcome new readers and thank you for reading this series. I cannot forget to thank

who mentioned the last installment on Atlanticism on his own publication (which you must absolutely check out if you haven’t already) for which I am eternally grateful.This entry is a bit lengthy, and yet there are so many more passages I would have wanted to include. It really is a pleasure to read the thoughts of this great man and an even greater one to share them with you.

Previous Entry: On Algerian Independence, Integration

On his conception of Europe

According to the same procedure as the first time, passing through René Brouillet's office, I was received by the General on January 27, 1960. He immediately declares with sadness in his voice:

"You see (he no longer calls me 'Monsieur le député'; I have moved from one circle to another: that of visitors familiar enough for him to no longer call them by their function, but not yet familiar enough for him to call them by name). You see, there are not many true Europeans. I sometimes wonder if I am not the only one. There are people who are looking for positions and advantages.

"There's Luns, who wants to make Europe, provided he is the Trojan horse of the Anglo-Saxons… There's Spaak, who is trying to contain the centrifugal forces of Belgium by surrounding it with a European bunker. There's Adenauer, who would prefer to avoid the reunification of Germany by integrating West Germany into Western Europe and postponing the possibility of an agreement with East Germany. For these two, Europe would be convenient: you think, it would prevent the breakup of Belgium and the unification of Germany... There's Pflimlin, who wants to favor the position of Strasbourg for the seat, to the detriment of Paris, which everyone except him would find more practical. They all want Europe only because it suits their little interests. I want Europe to be European, that is to say, not American.

AP: "You've always had a ‘certain idea of France’: have you always had a certain idea of Europe as well?"

CDG: "I didn't wait for the enthusiasts of The Hague to discover that there was a Europe and that it could and should be organized. Look at my texts from before the war, during the war, and after the war, and you'll see that I've always advocated for the union of Europe. I mean the union of European states. Read what I've been saying for more than a quarter of a century - there might even be an advantage in bringing these texts together. I haven't changed. I want Europe, but Europe of realities! That is to say, the Europe of nations - and of states, which alone can answer for nations."

AP: "If you don't want an integrated and supranational Europe, how do you practically see the European Union?"

CDG: "The guidelines are clear as daylight. As for the details, we will discuss them another day when I have more time; here are the main points. The first idea is that Western Europe must organize itself, in other words, that its states come closer together, from Amsterdam to Sicily, from Brest to Berlin, in order to become capable of countering the two mastodons, the United States and Russia.

As long as our countries remain scattered, they are an easy prey for the Russians, like the three Curiatii arriving separately against the Horatii; unless the Americans protect them. They therefore have a choice between becoming Russian colonies or American protectorates. They have preferred the second solution and we understand why it has prevailed at first. But it cannot last forever. It is therefore urgent that they unite to escape this alternative.”

[…]

After the council, the General, speaking slowly as if for me to take notes, gives me a rather calming orientation for the public:

"France's policy is to create a Europe that is one, that exists by itself, that has its own economy, defense, and culture. It is a subject that must be dealt with objectively and without passion. France is deeply committed to European construction. It is within a European framework that we now intend to place our national life.

We are stubbornly building the common market. We would like the British to be able to contribute to it as much as we do. We want a coherent and closer continental system and a much more stretched Atlantic system, where Europe would be on equal footing with the Americans, who currently have all the power.

We hope that, in the very near future, Great Britain will evolve enough to anchor itself to the continent and prefer it to the 'high seas.' It is essential that it be able to accept all the constraints of our Europe of the Six. It is clear that it has not yet done so. Negotiations for its candidacy can only resume when it does."

On the Franco-German relationship

CDG: “It must begin with these five or six countries, which can form the hard core; but without doing anything that could block the road for others, Spain, Portugal, England if it manages to detach itself from the Commonwealth and the United States, one day Scandinavia, and why not Poland and other satellites when the Iron Curtain finally lifts. The second guideline is that Europe will be made or not, depending on whether France and Germany reconcile or not.

It may be done at the level of the leaders; it is not done in depth. The French continue to hate the Boches1. There will be no European construction if the agreement between these two peoples is not the keystone. It is France that must make the first move, for it is she, in Western Europe, who has suffered the most.”

AP: "The Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark, England, also suffered..."

CDG: "It's not the same thing. France suffered more than the others, because it is the only country whose legal government collaborated with the enemy. Others were occupied, others suffered deprivation or abuses. But no other saw its leaders sell their soul. The Dutch, Belgian, etc peoples were looking towards London, where their governments were in exile. That's where their legitimacy and hope had moved. They had no doubt about the way to follow. They were not deeply divided. The harm that Vichy did was to make the French believe that France would get out of it by collaborating, and even that it had an interest in Germany's victory.

That is why France suffered more than the others: because it was more betrayed than the others. That is why she alone can make the gesture of forgiveness. Germany is a great people who triumphed, then was crushed. France is a great people who was crushed, then associated with triumph. Only I can reconcile France and Germany, since only I can lift Germany from its decadence."

("Great people!" I think of the story told to me by Jean Laloy, my senior from the Quai d'Orsay2, who, as an interpreter, accompanied de Gaulle to the USSR at the end of 1944. The Soviet authorities were showing him the battlefield of Stalingrad. The General was looking at the still intact ruins in the distance. He exclaimed, "What a great people!" Laloy immediately translated to the Soviet companions, who expressed their satisfaction. The General then added, "I'm talking about the Germans.")

[…]

The year 1963 not only begins with the General's big refusals: the refusal of the Common Market for England, the refusal of the "multilateral force" for the Americans; it also begins with a great commitment, that of France and Federal Germany, in a solemn treaty.

Adenauer and the General will sign it at the Elysée.

Couve announces it at the Council on January 3, 1963: "The Chancellor is coming to Paris on January 21 and 22. Franco-German cooperation will take shape.

CDG: “We will do together what the Belgians and the Dutch prevented us from doing with six. But these two count much more than the other four put together."

The General is as laconic as Couve, but he does not follow him in the terrain of litotes...

At the Council of January 9, 1963, Couve first reviews the multilateral force following the Nassau agreement: "The Germans, on the one hand, fear that Britain and France have a special position in NATO from which they would be excluded; on the other hand, they want a share in the nuclear field and are attracted to the multilateral force.”

CDG: “The Germans have complexes. We must understand them."

The General is all indulgence. The prospect of new Franco-German links makes him hope that their power of attraction will be stronger, and that Germany, led by France, will know how to ‘decolonize’ itself.

[…]

The General becomes serious again: "The political state of Germany is a much more grave and much more concerning issue than the upheavals caused by the agitation of the Anglo-Saxons. We have just concluded a treaty with a Germany that is troubled in its soul. The Chancellor is at the end of his term.

Candidates for his succession are agitating. This creates a political atmosphere that is not happy. The Germans will ratify the treaty, while saying that it is not sufficient or that it goes too far. If they do not ratify it, our conscience would be clear vis-à-vis them and vis-à-vis Europe, and we would then find another orientation." (He reiterates.)

AP: "In that case, would it be a reversal of alliances? Would you turn to Russia, as you did in December 1944?"

CDG: "Sure, you can say that. And with more chances of success. Stalin is no longer there, the world has changed, the Russian Empire is cracking, its military and ideological imperialism is retreating. In Germany, I fear that a new Weimar Republic is preparing. We are dealing with people who are administratively serious but not very political. The best thing is still to get them used to adhering to France. Without us, God knows what they would adhere to!"

[…]

CDG: "So, they grumble and resist in the face of the Franco-German agreement. The Anglo-Saxons fear they will no longer be able to intervene in the Franco-German intimacy. Since I stood up to them, it was inevitable that they would unleash themselves. For centuries, the English have tried to avoid intimacy between the Gauls and the Germans.

This is now also the case with the United States. How can we be surprised that the firmness of my position and the support I receive from the Chancellor provoke a reaction from them and from the many brilliant French supporters of America?

The press pretends to believe that the essential thing in the last three days was the 'Brussels crisis' and that the Chancellor and I were mainly concerned with that. Of the five hours of tête-à-tête conversation we had, about five minutes were devoted to Britain's entry into the Common Market, and they consisted of noting that we were completely in agreement."

[…]

Salon Doré, after the Council.

I approach another aspect of the subject: "Our partners are tempted to give up everything to the Americans and abandon the Common External Tariff."

CDG: “Europe must decide to be Europe. It must overcome its feeling of inferiority towards America, which is, after all, only its daughter. Europeans must prefer Europe to America, damn it! As long as they do not resolve to do so, there will be no Europe."

And when I venture to insist on the press's reception to the announcement of a new distancing from the Americans, the General rebukes me:

"You all think of only one thing, which is to avoid making the editor-in-chief of La Dépêche du Midi grumpy! Haven't you understood that all these newspapers have no other importance than the one you give them?"

[…]

Salon doré, April 24, 1963.

To obtain a broad ratification from the mistrustful Bundestag, Adenauer has resigned himself to adding a unilateral preamble to the treaty that affirms the "Atlantic" solidarity of Germany, thus reducing the European scope (in the Gaullian sense) of the treaty.

The General asked me to present this official version of our reaction to the press:

"France has informed the German government that it has no objection to the inclusion in the German ratification law of a preamble reaffirming the Federal Republic's loyalty to its Atlantic and European commitment."

But the General's felt truth is quite different:

"The Americans are trying to empty our treaty of its content. They want to turn it into an empty shell. Why is all this? Because German politicians are afraid of not bowing enough to the Anglo-Saxons! They behave like pigs! They deserve us to denounce the treaty and make a reversal of alliance by reaching an agreement with the Russians!"

Adenauer visits de Gaulle

CDG: "I wonder if, despite the Franco-German agreement, we will succeed in setting up the Common Market before negotiations with the United States. We wanted a common policy, and that is why France took a stand against the entry of the English, under current circumstances, into the European Community." (He speaks more firmly.) "The Franco-German Treaty of Friendship is, for now, a treaty of intent. It is necessary for it to be otherwise. There is no other European reality than Germany and France, and if these two realities are not united in all areas, we will be overwhelmed."

Adenauer then becomes decidedly pessimistic about Kennedy's reliability and the European disposition of the English. The future of the Common Market does not cheer him up any more: "I will do everything possible to ensure the survival of the Common Market. But I don't know if I will succeed. If social and public charges are not harmonized, as the treaty stipulates, there will never be a true European economic community. I also add that German agriculture will have to change its structure. This would allow French agriculture and German agriculture to operate side by side."

CDG: "I agree that in France as well, much remains to be done to modernize agriculture. I think an agricultural settlement must absolutely come before negotiations with the Americans begin. Otherwise, they would overwhelm Europe with their surpluses."

Adenauer: "Franco-German friendship is the most important result of all my activity during the fourteen years I have led German politics."

[…]

The Chancellor continues: "I would like to see stronger ties between us in the military realm. However, we must not forget that the Americans are our only real protection against the Soviet danger."

CDG: "The presence of the Americans, for a long time to come, is a necessity, and NATO is another. But this organization was created at a time when neither Germany nor France had regained their reality. It is now important that we exist on our own and together be the nucleus of a Europe capable of becoming truly European, that is to say, independent. The more time passes, the more our agreement will find fields of application."

Adenauer: "Even just the exchanges of units between France and Germany, which have mainly symbolic value. The welcome of French troops by the German population was very warm."

CDG: "I do not think that this exchange of units between our two countries, which has mainly symbolic value, solves the problem of cooperation between our two armies."

For the Chancellor, the bottle is half full. For the General, it remains half empty.

Adenauer: "With the prestige you have restored to France, General, you would be assured of being able to successfully create an international diplomatic institute for the training of diplomats from all countries. Students from everywhere would come there."

CDG (unenthusiastic): "Yep3."

Adenauer: "Really, General, if you were to establish this institute in Paris, all you would need to do is hold a conference there every six months… (seeing that the General is not responding, the Chancellor lowers his expectations) or every year. It would have an immense impact. You would have a great means of influence for France."

The General remains expressionless. This idea seems fanciful to him. The very idea of international diplomatic teaching is foreign to him. In the end, there is only one diplomacy that interests him - that of France. To lead it, yes; to teach it, especially to foreigners, does not interest him in the slightest.

In the face of the mediocre reception of this suggestion, the Chancellor puts forward another.

Adenauer: "You should go to the UN, you would have great success there."

CDG (coldly): "No, don't count on it."

Adenauer: "You should, everyone would applaud you."

CDG: "They would applaud me because they would say that de Gaulle is surrendering! People always applaud those who surrender. Those who never surrender are looked down upon."

Adenauer: "You were right when you said that the UN can no longer be of much use. As it grows, it loses its importance. Eisenhower and Dulles told me: 'We made a mistake by letting in the underdeveloped countries. Soon, it will be all about them.' The Americans are realizing this now."

CDG: "The Charter is not being implemented. I am not against the UN because it is the UN. I would be for the UN if it applied its Charter. A chaotic Assembly that adopts demagogic resolutions, a Secretary-General who undertakes military expeditions outside the Security Council, that is not in line with the Charter. We don't want that. I won't go to the UN until it applies its Charter."

Adenauer: "In short, you want it to surrender."

The General laughs; it is a pleasure to see that age does not diminish the Chancellor's wit. But he remains impervious to his host's imaginative exhortations. So Adenauer falls back on a topic already discussed in the afternoon.

Adenauer: "Did you see the note the Russians sent to the Chinese?"

CDG: "Yes, but it's just a note."

Adenauer: "We never would have imagined this a while ago! You predicted it."

CDG: "It couldn't end any other way, but they're not yet at the point of open conflict."

Adenauer: "The day it really goes bad between them, Russian troops will be massed in the East, because the Chinese will covet Siberia, while the Russians will know that the Americans are not a threat."

CDG: "We still have to prepare for that day, and we can't let Europe be caught off guard when it happens. On that day, the Soviet Union will fall to pieces, and Europe can regain its unity, its freedom, its independence."

On preserving the character of each peoples

The General resumes:

"The third guiding idea is that every people is different from the others, incomparable, unalterable, irreducible. It must remain itself, in its originality, as its history and culture have made it, with its memories, its beliefs, its legends, its faith, its will to build its future. If you want nations to unite, don't try to integrate them like you integrate chestnuts into a puree.

Their personality must be respected. They must be brought closer, taught to live together, bring their legitimate rulers to consult with each other, and one day, to confederate, that is to say, to pool certain skills, while remaining independent for everything else. That's how we'll make Europe. We won't make it any other way.

The fourth idea is that this Europe will come into being on the day when its peoples, in their depths, decide to join it. It won't be enough for parliamentarians to vote for ratification. There will have to be popular referendums, preferably on the same day in all the countries concerned."

On the Treaty of Rome, supranationality, and dealing with European bureaucracy

Brouillet then led me into the General's office.

"So," the General said imperiously, indicating a specific armchair across from him, "I am told that you are an expert in Brusselian bureaucracy4?"

I (modestly) replied, "Expert is an overstatement. I participated in the negotiation of the treaties of Rome and their implementing regulations in Brussels for two years."

The General then drew my attention to the confidential nature of the meeting before getting to what concerned him:

CDG: "After the rejection of the European Defense Community, the architects of this project avoided using the words 'supranationality' and 'federalism' like the plague. They realized that they would face a new failure if they went all in. But they haven't changed their beliefs. They are determined to establish, as they say, the United States of Europe, with a super-federal government composed of the current commissions, which would oversee provincial governments—the current governments of the States—which would only deal with secondary issues."

AP: "That's the Monnet system. It consists precisely in creating situations from which the only way out is to increase the dose of supranationality. Each new difficulty leads us further into a mechanism that pushes towards a federal state and takes away more power from national governments."

CDG: "We don't want that! It won't happen! It would be foolish! Of the two Treaties of Rome, I don't know which is the more dangerous. The Euratom treaty is more than useless, it's harmful. I wonder if we shouldn't denounce it. And then there's the Common Market. It's a customs union that can do us good, provided the agricultural common market is realized, which is not established, and some other common policies, which are not even outlined.

But it also includes pretensions, what are called its 'supranational virtualities,' which are not acceptable to us. ’Supranationality’ is absurd! Nothing is above nations except what their states decide together! The pretensions of the commissioners in Brussels to want to give orders to governments are ridiculous! Ridiculous!"

AP: "What you want is to render inoperative the dose of supranationality included in the two treaties of Rome - the Common Market and Euratom - but also, it should not be forgotten, the even stronger dose found in the 1952 Paris Treaty on the Coal and Steel Community? It seems to me that it is not necessary to denounce these treaties, which would cause a huge scandal. It is enough to impose, as long as we are not yet in supranationality, a jurisprudential interpretation that excludes supranationality for later."

CDG: "How do you plan to do it?"

AP: "For Euratom, it's not difficult. Since we are the only one of the six countries to have a powerful organization dedicated to atomic research, we simply need to refuse to participate in the construction of any other equipment or to allow our researchers and engineers to be put at the disposal of others. We just have to invoke the needs of the service. There will be no community atomic installations, unless we are the ones who realize them."

CDG: "Of course! It's a thingamajig where we give everything and receive nothing. It's incredible that French governments have been able to sign this, and that parliamentary majorities have been able to approve it."

AP: "Why kill Euratom spectacularly, when all we need to do is let it wither away by not feeding it?"

CDG (skeptical): "Do you think so? If we denounced it once and for all, we would never hear about it again."

AP: "We will hear much less about it, my general, if we let it dry up slowly. As for the Common Market, it works until the end of the second of the three stages of four years each, that is to say, in principle until January 1st, 1967, according to the unanimity rule. Before the end of the second stage, we can veto any decision. But above all, we can, at the last moment, veto the decision to move on to the third stage, from which decisions would be taken by majority. We would remain definitively in the second stage. Or, preferably, we can make it a condition, before accepting to take the leap, that our veto is preserved for the questions that we consider essential."

CDG: "We must guard against the risk of being overwhelmed. Harmonizing the practical interests of the Six and organizing their economic solidarity vis-à-vis third parties is good. But there is no question of moving, using the same method, from the economic domain to some kind of 'integration' of politics, diplomacy, and defense. These are nonsense. We will not allow ourselves to be dispossessed of our powers. We will not allow ourselves to be subordinated! France is not to be confused!

Monnet, Pleven, or others of the sort believe that France is only a small country, that it does not carry weight to play a global role, and that it has therefore only to submit to others. Fabre-Luce has even written that since the French have shown for two centuries that they are not capable of governing themselves, supranational integration will allow the Germans to teach us organization and discipline. All of this is monstrous! Monstrous!

I do not rule out, for later on, a confederation, which would be the culmination of a patient effort to develop a common policy, a common diplomacy, a common security, after a long period in which the six states had become accustomed to living together. I will make proposals in this direction to Adenauer. But this can only be done through consultation with legitimate governments. And not by rootless technocrats.”

As he accompanied me to the door, the General casually asked me, "Can you give me a note on practical ways to stifle supranationality? And while you're at it, you could write some articles to popularize these ideas of state consultation, confederal construction, and a European referendum. Your pan-European committee's monthly bulletins are good, but only short excerpts are seen in the newspapers. We need to feed the mainstream press."

[…]

AP: "Do you expect anything from the NATO session?"

CDG: "What do you want me to expect? NATO is useless: nothing can happen there! It's all zero, zero, zero. It's designed to keep international civil servants who get paid handsomely for doing nothing without paying taxes.

AP: "We will not revisit the withdrawal of our naval officers from NATO?"

CDG: "Why do you want us to go back to that? There was no reason for them to stay there. It was an anomaly that they were there. Of course, they were paid more than if they had stayed in the French navy. These international organizations are good for catching venereal disease. Our representatives forget their duty of obedience to the state. They lose their national feeling there."

AP: "The matter was made public from Germany. We had informed them of our intention, as part of the consultations provided for by the Elysee Treaty?"

CDG (surprised): "No, I don't think so. Why should we inform them? No. It had to be known sooner or later."

AP: "It was Die Welt that leaked it."

CDG: "The English, who are masters at manipulation, have colonized the German press. Adenauer was the first to complain about it. The Germans are bound by their press in the hands of the Anglo-Saxons.

Do you know what supranationality means? American domination. Supranational Europe is Europe under American command. The Germans, Italians, Belgians, and Dutch are dominated by the Americans. The English are too, but in a different way, because they are of the same family. So, only France is not dominated.

To dominate it too, they keep trying to make it enter a supranational thing under Washington's orders. De Gaulle doesn't want that. So, they are not happy and they say it all day long, they put France in quarantine. But the more they want to do it, the more France becomes a center of attraction. Can you see us swallowing supranationality? Supranationality was good for the Lecanuets5!"

[…]

He repeated in the speeches of this tour (as he had already done during his tour of last June in the Jura) that the European Economic Community should become a "political community." I ask the General if this is intentional.

CDG: "Of course! It must be the case! The European Economic Community is not an end in itself. It must be transformed into a political community! And even, it can only continue to be a real economic community if it eventually becomes a political community. It was because the English were not ready to enter into a political community that ultimately they should not have been brought into the economic community. Political will is the driving force behind economic unification.

AP. - But wouldn't the political institutions resemble the institutions of the Economic Community?

CDG. - Obviously! Not at all! On the contrary, they must be profoundly different. There is no question that a commission like that of the Common Market can regulate the foreign or domestic policy of the six countries. But we must learn to cooperate. And when this learning is done, the institutions will tighten themselves.

AP. - Do you think that after a few years of political cooperation training, we could create a common executive, like the one in Brussels?

CDG (brusquely). - There is no executive in Brussels. Your executive does not execute anything at all. What is falsely called the executive is only a commission of contact, coordination, and preparation of decisions. But the decision belongs to the governments. It cannot be otherwise. If the commission arrogated the power of decision against the governments, it would be sharply put in its place. It wouldn't take long. And we wouldn't be the only ones to react. Calling the commission in Brussels an executive is just one more pretense. We have said goodbye to pretenses. We are doing politics of truth. But what is possible is that after the training in political cooperation, we may get used to making decisions within the Council of Ministers.

AP. - By majority or unanimity?

CDG. - We must start with unanimity, and we will see. I cannot say what will happen fifty years from now. But perhaps we will have to wait fifty years for a true political community to emerge."

Fifty years: this is the first time I've heard him pronounce, even in private, a figure that sets a rough estimate. The General doesn't believe that it's possible for Europe to really come together on the scale of a generation. He guessed my thoughts.

CDG: "Peyrefitte, look at the United States. It took them eighty years, from the Declaration of Independence to the Civil War, to move from the stage of a confederation to that of a federation. Canada is of the same order. The Netherlands took seven hundred years for a comparable evolution. And Switzerland, too, several centuries."

He concludes: "The babblings of the prophets of Strasbourg, of Pflimlin and Spaak, leave me cold. Centuries of history are not erased in one stroke."

On the entry of the United Kingdom into the European Community

He returns to some of the points raised at the Council:

"It is absolutely out of the question to mention NATO in a European treaty! How can Europeans be so little European as to want to make a treaty among themselves only under the invocation of the Americans? They have no sense of the dignity of Europe! The Union treaty constitutes a permanent and definitive commitment of the six States, while NATO is a circumstantial organization, born of the Soviet threat and destined to disappear one day, when it will have disappeared itself."

Almost in passing, he evokes the end of the East-West confrontation that we have become accustomed to consider as an eternal given. He projects himself so spontaneously into the long term that our present is already his past.

"Why do you think that the Belgians and the Dutch, but also the Italians, demand both supranationality and the entry of England? Obviously, it is because they know very well that it could not work! They hope that the great powers would spend their time disputing; the small powers would take advantage of this fight to play elbows and assert their point of view. It's like the hinge groups under the Fourth Republic, which took advantage of the quarrels between the major parties to claim a disproportionate role to what they really represented.

Macmillan told me in '58: 'It is to prevent the union of Europeans that we waged war against you for twenty-three years, during your Revolution and your Empire.' For the English, the Common Market is like the Continental Blockade! Ha! Ha! (He is willing to laugh.) I prevented them at the end of '58 from suffocating it from the outside by drowning it in a large free-trade zone. Now they are trying to blow it up from the inside, through the Dutch and Belgians. If they don't succeed by this means, they will try to paralyze it themselves, after being admitted to it. Don't worry. They have persistence in their ideas. But so do we. And from now on, we will have the means for it."

[…]

CDG: "There has indeed been a strong evolution. In 1958, Macmillan showed fierce hostility towards the Common Market, which he wanted to drown in a large free trade zone. He was even more opposed to a political union of the continent. He gave up on his big zone and is even ready to give up the small one. It's a real rout! He has lost all hope of sinking the Common Market and of maintaining the Empire. He is therefore looking for another national and, consequently, international area of activity.

He sees Europe in a very different way. He is ready to practice it economically and politically. On the economic level, he is determined to overcome obstacles. Agriculture is one of them, but he claims that if given until 1970, he can make English agriculture competitive; that doesn't bother him. Regarding the Commonwealth, obviously, he feels a contradiction. The new Britain has given up the Empire and would be willing to move beyond such regrets, but the existence of white dominions, from the point of view of Britain and the free world, counts so much that it would be unfortunate to part with them. He is therefore divided. 'I feel two men within me.'

"I told him: 'I see that you are evolving. We need to settle things thoroughly. Therefore, you need to evolve even more. We'll see this year how you go towards the Treaty of Rome. Will you endure all its constraints? Will you get up to speed? The common external tariff implies that you limit your imports from outside and therefore your exports outside the Common Market. Will you make it? Will your currency hold up?'

Missoffe (in a low voice). "So basically, de Gaulle said to Macmillan, 'You're the negro, well, carry on!'"

CDG: "On the political level, Macmillan praised de Gaulle's proposals; the rest is humbug. But there is no real political Europe if it does not have an identical economic basis, in other words, if Britain does not enter into political union and economic community simultaneously.

He made an extraordinary discovery: if we want to create a political Europe, it is nothing if it is not independent. Now, the criterion for independence is defense, but how can we give up the American protectorate?

In short, he took a very different tone from the one he took until now. He doesn't mind at all that France has its bombs, its strategy, its plans. That is entirely new. He has an obvious desire to do something new and to do it in Europe, not elsewhere. He has the notion that everything goes through France. He didn't understand this in 1958. Now he has to get used to it."

At the end of the Council, I try to find out more.

AP: "Do you really believe Macmillan is ready to upset the currents of exchange, the habits of consumers?

CDG: "He has affirmed it to me. He claims that in the past, it was unimaginable to run for election where you would have been accused of wanting expensive bread; but today, it doesn't matter. He doesn't even expect any political difficulties. He is aware of the extreme historical importance of the choice that England is about to make. He assures that the British Empire belongs to the past. There will only remain a vague mechanism like that of the UN. Kipling's England is dead. (It is impossible to know whether it is De Gaulle translating Macmillan or Macmillan quoted by De Gaulle.) The youth consider that their future is now linked to that of Europe. This new state of mind marks, according to him, a fundamental change that would appear in all environments, in all parties. British businessmen would also be preparing for the Common Market.

He doesn't care about his agriculture. It only employs 4% of the population, while in his younger days, it was 20 to 25%. Our problem is similar, except that the evolution of the English has gone much faster than ours. The problem they have behind them is ahead of us.

The fate of our agriculture is now, after the settlement of the Algerian issue, our biggest problem. And if we don't solve it, we can have another Algerian affair on our own soil. Our industry can face competition, but if our agriculture were to remain outside the Common Market, the burden that would result for our industrialists would be unbearable.

However, it has been so difficult to agree with our partners on agriculture, and there are still so many difficulties, that I don't see how we could now devise another regime. In any case, the entry of England would be such a upheaval that it would then be another Common Market."

AP: Is Macmillan really ready to adhere to the Fouchet plan, as the Prime Minister has suggested?

CDG: He agreed with me. Trying to belittle the States, to rely on commissions of wise men, is not serious. The peoples will never accept a government that is not their own. So, I told him straight out, 'Our will is to become independent from the Americans. Are you ready for that?'

He replied that the young people in England and he himself thought like us. They do not want to be American satellites. He envisions a free world organization that would be based on two poles: Europe and America. I objected that if England entered, other countries would also enter; what works difficultly with six would not work at all with ten or fifteen. But he is so determined that I would have been rude if I had completely discouraged him. However, I concluded by telling him that when you hesitate on the goals to pursue, it is better not to commit. It is better than committing tentatively, then backing down.

You see, France's goal is to make Europe. With the English if they can join, without them if they cannot. But the essential thing is that Europe wants to exist on its own, independently of the United States. I am not sure that England, and also neither Germany nor Italy, are determined to do so. If England is content to put a small part of its forces in NATO and keep the bulk in reserve on its territory under its sole command, as well as its strike force, then our concepts are identical. But that is not the prevailing concept in NATO, where defense of Europe, nuclear or conventional, is simply handed over to the Americans. It is useless to create Europe if it is not to have its defense and consequently its policy."

[…]

At the Council of Ministers on August 8, 1962, there was talk of Great Britain and its entry into the Common Market. Couve has an astonishing virtue: he is a breakwater. He is superbly cool around a green carpet. He has no equal in stopping the momentum of his interlocutors. "I have already said... It is pointless to repeat..."

"Among the Six," Couve summarizes, as always, "we are the only ones with a determined line. The problem is to bring Great Britain into the Common Market under the conditions of the Common Market, not to adapt the Common Market to the conditions of the Commonwealth. We are supported without any failing by the Commission, the guardian of the Treaty of Rome.

The Germans and the Dutch are in favor of Great Britain's entry into the Common Market, even if it means changing the Treaty of Rome. They are surreptitiously hostile to us. The Italians are in favor of England's entry, trying not to change the treaty. The Belgians have no position at all. They are unbearable people.”

CDG. - This negotiation is very complex. The Minister of Foreign Affairs has conducted it very well. We remain the main interested party for agriculture, which we must modernize by ensuring outlets. It is a major national issue. We need to get our agriculture going just as our industry has already started. The Common Market must help us with this.

If England does not comply with this necessity for our agriculture, the Common Market will be much less interesting for us. We cannot give in. Accepting a transition until 1970 is conceivable; but on condition that the Common Market is a whole, with agriculture in particular; that there is no breach. The policy of the English is to have a breach through which many things can pass.

What will happen? The Conservatives want to be the ones who have brought the Common Market into the Commonwealth. Macmillan, for his part, would be ready to bring England into the Common Market without conditions. But he faces a very complex situation that is difficult to control.

A trade treaty between Great Britain and the Common Market is not inconceivable; it can be advantageous for both parties. Bringing Great Britain into the Common Market is another matter. It is up to them to decide, in other words, to accept the sacrifices that this entails. In the political conditions in which they find themselves, it will be difficult for them, if it is even possible.

There is all the weight of the Commonwealth, tradition, and currents that are playing out in the situation to overthrow a conservative government. Let us not wish ill on Macmillan, who is a sincere ally of France. But we cannot sacrifice a fundamental French interest for this sympathy.

We will not change our position.”

On European “integration”

Salon doré, December 4, 1963.

AP: "I venture to suggest that it would be better to speak the same language as our European partners, so as not to offend them: 'It seems to me that we would be wrong to set appearances against us by taking arrogant postures.'"

CDG: "Yes! We must say things plainly. Appearances are ephemeral, realities remain. To be agitated in the world of appearances means sacrificing what matters to what does not matter. It means demagoguery. Why fear saying things? We are respected all the more for saying them. If the world admires France, it is not because she is a weak partner. It is because she is a partner who knows what she wants and dares to say it."

AP: "It still seems to me that it would be unfortunate to attract blows that we could avoid."

CDG: "Look at the problem from a higher perspective, Peyrefitte! What have European projects been about for the past 50 years? To give Germany back its coal, its army, its place in Europe. But because we did not dare to do it directly, for fear of defying public opinion, we did it behind a screen, in a cautious way. The same was done for Italy, which was absolved of everything it did during the war. It was a way, without making it too obvious, to make them into countries that could look others in the eye. I am not against it, in fact, that's what I'm doing; but one must not be fooled; and it is good that they do not forget that we could have done otherwise.

And then, Europe was a way of making small countries, Belgium, Holland, not to mention Luxembourg, the equals of the great powers. In a European Council, Spaak is worth General de Gaulle, and even more: in a meeting of these people who belong to the same club, he will always be right. He knows the passwords. He knows what pleases all these little gentlemen.

Integrated Europe could not suit France, nor the French... Except for a few sick people like Jean Monnet, who are above all concerned with serving the United States. Or for all those lamentable figures of the Fourth Republic. They thus found a way to unload their responsibilities! They were not able to grasp them; so, they had to pass them on to others. To hold their rank in the world? No way! Let's get under the umbrella. To have an army and make it obey? No way! Let's give it to others! To put the country back on its feet and serve as an example to the world? Not for them!

The ready-made alibi was Europe. The excuse for all evasions, all cowardice: integrated Europe!"

AP: "So, you resign yourself to seeing this Europe disintegrate, cease to exist?"

CDG: "This Europe, it does not amount to much! It is a handful of talkers who strut their stuff in endless conferences, who do not know what they want, who do not want what they know. They make proposals with the hope that they will not come to fruition. They count on others to torpedo them. But in the meantime, they will have given themselves a favourable appearance."

On the proliferation of “international/european organizations”

The multiplication of international conferences gives the General the impression of wasted time and resources.

At the Council meeting on April 15, 1964, the General said: "Mr. Fouchet is in London for a conference of European Ministers of Education. What is this, again? What does it result from?"

Joxe, who is temporarily replacing Couve, supposes that it is in the framework of UNESCO, but Triboulet leans towards the Council of Europe.

CDG: "But what is it for? Doesn't a Minister of National Education have anything more useful to do?"

Joxe (hesitant at first, but doesn't want to be dismantled): "It's to ensure the mobility of students."

CDG (grumpy): "It mainly ensures the mobility of ministers."

Pejorative term for Germans, popular amongst the French infantry of WW1.

The Quai d’Orsay, quay located in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, is often used as a term for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs housed in the Palais Bourbon in the same area

De Gaulle uses the informal ‘Ouais’ instead of ‘Oui’.

I thought it would be funny to point out that the word he uses here in French is “chinoiseries” aka Chinese manners.

French center-right politician, he was a believer of European integration and sought to create a “third way” between Socialism-Communism and Gaullism. Often called the “French Kennedy” by the press.